Duggan’s fate hangs in the balance as his lawyers keep their powder dry

May 29, 2024

The Magistrate hearing the United States application to extradite Australian citizen and father of six, Daniel Duggan, was floored.

Duggan’s lawyer Bret Walker SC had walked into the courtroom late and in a short statement informed him there would be “no submission” further to a document in Duggan’s own words, as there were “no legal grounds”.

The Australian heralded the news very quickly in a headline since replaced: “No arguments to make against extradition: ex-pilot” but this certainly did not mean there were no legal arguments. Walker’s statement merely acknowledged the futility of running them when a magistrate could not take them into account.

I had been expecting a truncated rerun of Assange’s Extradition hearing in UK Magistrate’s Court where, over 4 weeks of evidence presented by his legal team that included testimony from over 20 expert witnesses, there was an underlying expectation this must all be taken into account in Vanessa Baraitser’s decision. However, the Prosecutor for the United States made it very clear throughout, she had no authority to rule on the merits of the evidence.

There were very few grounds on which Baraitser could deny eligibility for extradition - health was one. Though she did indeed rule Assange could not be taken to the US because of his health, the US successfully appealed on the basis she had not offered an opportunity to the Prosecution to furnish the Court with Assurances that the US prison he would be placed in could and would implement measures to mitigate any repercussions regarding his health, namely suicide. The US Appeal was successful in a higher court despite testimony submitted to the lower court as to the unreliability of US Assurances (2 well documented cases where US Assurances were reneged on), and, despite the fact that the Assurances supplied to the UK court regarding Assange were qualified - that is, they were able to be withdrawn so “not worth the paper they are written on” according to Amnesty International.

Assange’s Extradition was approved by Home Secretary Priti Patel, despite the UK’s law forbidding extradition to a country where the death penalty could be imposed.

On Assange’s Appeal, the Supreme Court judges sought an assurance against the death penalty and agreement from the two sides on the position with respect to Assange’s eligibility to First Amendment rights as a non American - that he will not be treated differently in an American Court to any American citizen.

Despite it being “very difficult” according to the lawyer representing the Home Secretary to extract an assurance regarding the death penalty, extract they did, and clearly no argument could be mounted against its reliability as the highest Court in the land had already indicated the word of the US was to be accepted. However, the other matter could not be “agreed upon” by the two sides – that would have to be argued in a US Court – it was not an assurance that was Executive’s to give.

Meanwhile in the 13 years this matter has run, he has been in detention of one sort or another, his heath has deteriorated, it has cost the UK taxpayer a fortune, arguably posed the greatest threat to press freedom in our lifetime and the matter in recent years is ping ponging between the courts and politicians. It holds salutary lessons in the snookering possibilities and the dead-ends. (It has to be said that though Assange was not given leave by the High Court to Appeal on all the grounds he sought, the witness testimonies in the evidentiary hearing nevertheless form an important public record of a significant press freedom case, and provided valuable information to journalists who could be bothered.)

So it is in light of what is possible under our Extradition Act that a defence has to be mounted. It appears Duggan’s legal team have cut to the chase, Bernard Collaery telling journalists outside court at the conclusion of the hearing:

“The attorney will give us sufficient time, I’m quite sure, to ventilate all of the issues that under the Extradition Act are not capable of being run in an Australian court.” It is in a US court that evidence can be tested.

Duggan’s defence can now make a Submission to the Attorney General under Section 22 of the Act, mounting arguments as to why he should deny extradition. The Attorney General’s role will come under scrutiny as he tries to balance his responsibilities. Meanwhile, Duggan, who is not charged with breaking any Australian law will continue to be held in solitary confinement in breach of UN Conventions.

I spoke to ABC NewsRadio on Saturday about the case that is extraordinary in its own way:

[audio mp3=“https://publish.pearlsandirritations.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/NR-Duggan-Kostakidis.mp3"][/audio]

It was an eventful start to the day as the family, neighbours, friends, supporters, journalists and lawyers queued at the door of a court only to be shunted three or four times back and forth to different courts on different floors.

We were finally let into a small courtroom with a dozen chairs, Duggan appeared in an enclosed dock behind glass, and Magistrate Daniel Reiss made clear his concern about rowdy protesters – it has to be said no one had actually been rowdy at this point - and asked all not seated to leave. Additional police officers entered the court. The crowd responded by sitting on the floor, among them long time advocates of social justice including Sister Susan Connelly. A couple of people shouted responses about open justice, the magistrate stuck to his guns and the court room emptied of all but a couple of standing journalists who were accommodated.

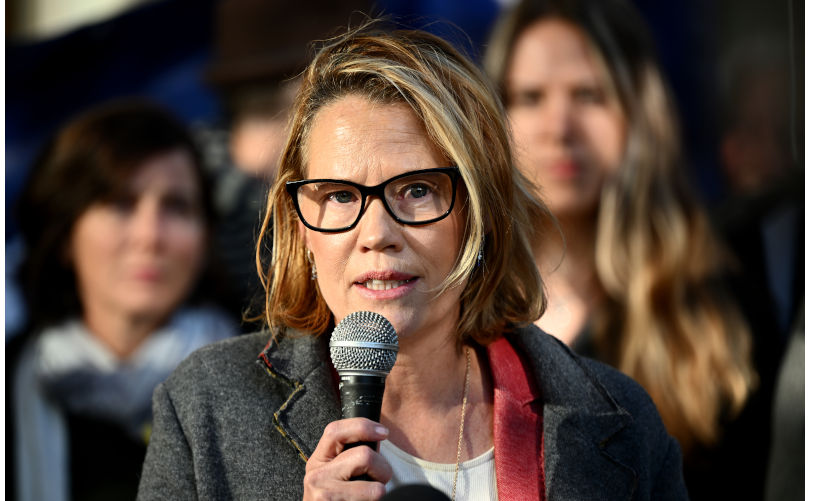

We then waited some time for Bret Walker, who had earlier been seen at the front of the queue waiting to get into court. He finally appeared with Bernard Collaery and Saffrine Duggan in tow. As Walker rose to address the Magistrate, Duggan’s wife, whose eyes were fixed on her husband, welled in tears.