Environment: Australia opposes nations’ legal obligations to tackle climate change

December 8, 2024

International Court of Justice to provide advice on nations’ climate change obligations. SE Australia and WA to experience more heat waves than predicted but NT and FNQ will have fewer. Mixed evidence of countries working together to progress sustainability.

International Court of Justice climate change hearings

You are possibly vaguely aware of but not well informed about the current hearings (running from December 2-13) regarding climate change at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Hague, Netherlands. The United Nations has provided a reasonable description of what it’s all about:

- The ICJ has been asked by the UN General Assembly to provide an advisory opinion (not a binding ruling) that will clarify nations’ legal obligations under international law with respect to climate change and the consequences of breaching them, with particular respect to:

- The protection of the climate system and other parts of the environment from greenhouse gas emissions for present and future generations,

- The legal consequences for nations where they, by act or omission, cause significant harm to the climate system and the environment, particularly where it affects states, peoples or individuals that are vulnerable to climate change.

- The process was started in 2021 when Vanuatu, pushed by the Pacific Islands Students Fighting Climate Change, announced its intention to seek an advisory opinion from the ICJ on climate change and began collecting support from other countries. In 2023 a resolution to this effect, sponsored by 132 countries, was adopted by the UN General Assembly and transmitted to the ICJ.

- This case is the largest ever heard by the ICJ. Over 150 written statements have already been received by the ICJ and over 100 countries and international organisations are expected to make oral statements to the Court during the current hearings.

- Although ICJ rulings are not binding on nations, they carry considerable moral authority, may influence diplomatic processes and domestic legal proceedings, and will probably, if the Court finds that countries have legal obligations, encourage nations wanting stronger international climate action to be more demanding.

- On Day 1, Vanuatu and other Pacific Island nations opened proceedings with arguments about climate justice, the right to self-determination, the role of international law in protecting the rights of all peoples, and the importance of accountability for past wrongs. This was followed by Australia joining Saudi Arabia and Germany to argue that states’ obligations in relation to climate change are predominantly found in the Paris Agreement and urging the Court to refrain from determining additional duties from other branches of law. (Good move, Albo, that’ll get the Pacific nations lining up to support your bid to host the 2026 COP meeting.)

- The Court’s opinion is expected in early 2025.

If you’d like to stay in touch with the hearings, you can get a daily update from World’s Youth for Climate Justice.

Australia’s heatwave hotspots

The Earth is getting hotter, the rate of warming is increasing and there are more extremely hot days (and other extreme weather events) - many people don’t need a scientist or weather expert to tell them any of that. Not so obvious is that the change in the number of heatwaves is not uniform across the world.

The climate models developed by scientists have been getting increasingly accurate at predicting the average temperature increase that is being experienced globally. They are not so good at predicting the changes that will occur at regional levels or changes to the frequency of extreme temperatures.

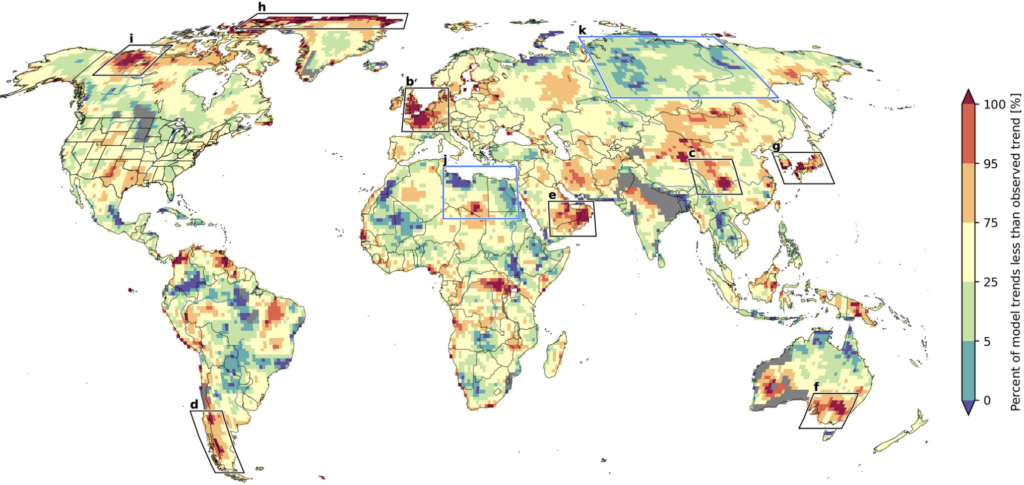

A study that has measured changes of extreme temperatures worldwide over the last 65 years and compared the results with climate model simulations has identified areas around the world where the models have underestimated the frequency of extreme heat events being experienced, and areas where the frequency has been overestimated.

The map below compares the frequency of observed heat waves with the predictions of climate models. The yellows areas are where observations and predictions match pretty well; the orange and increasingly red areas where heatwaves are significantly more common than predictions suggest; and the green and increasingly blue areas where they are less common. It’s obvious that while there is a lot of regional variation, there are some highly and densely populated areas (e.g. Europe and Central Asia) that are experiencing more heatwaves than predicted, and also some critical ecosystems (e.g. the Arctic and parts of the Amazon).

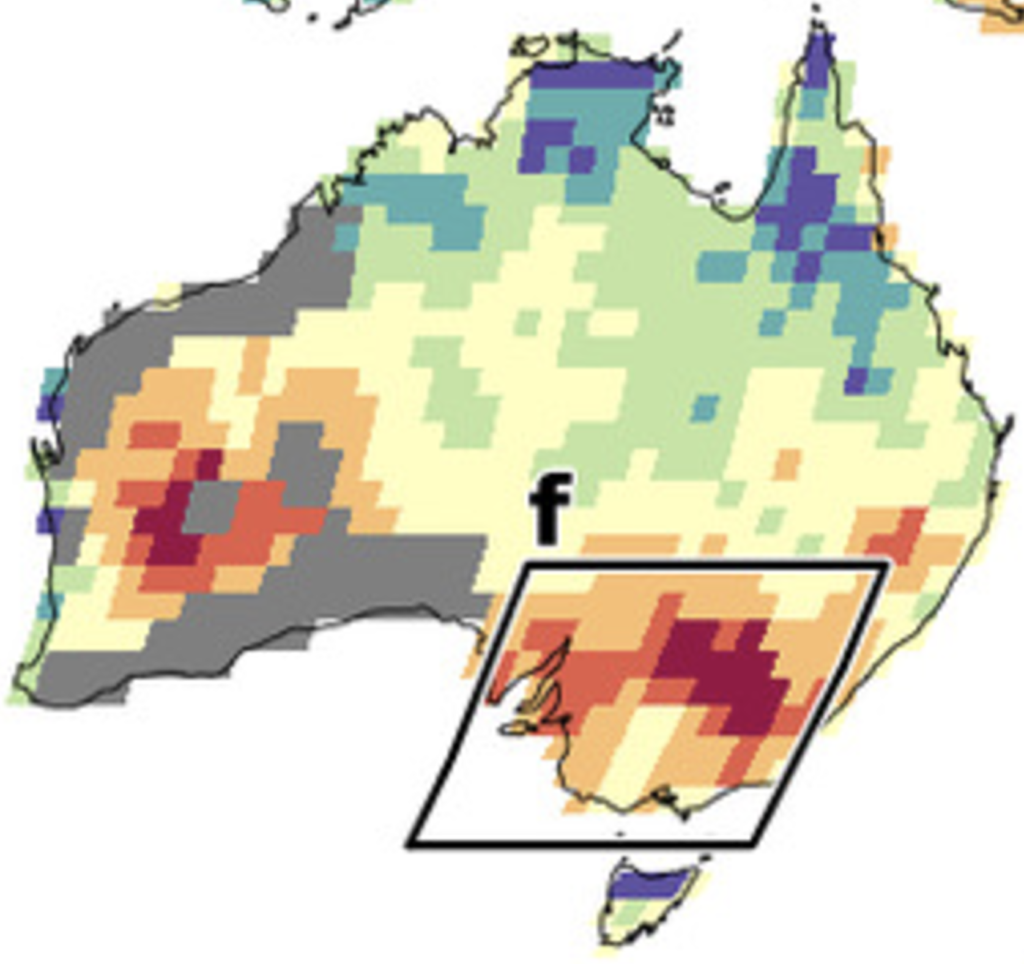

To help us see what is happening at home, I have blown up the Australian section of the map. It’s clear that south-eastern Australia and central WA have been experiencing more heatwaves than models predict. On the other hand, Tasmania, much of northern Australia, especially Far North Queensland and the north of the NT, have been experiencing fewer than predicted. There’s no obvious reason why these trends will change and the implications are obvious:

- Australia needs to do its planning for the increasing number of heatwaves (that can be disastrous for human life, communities, infrastructure and ecosystems) on a regional rather than national basis, and

- Scientists need to better understand the drivers of extreme heat and improve their climate models.

Just to avoid any misunderstanding, the green and blue areas do not mean that the areas around the Gulf of Carpentaria are getting cooler, nor that they have been experiencing fewer heatwaves than previously. They simply indicate that they have been experiencing fewer periods of extreme heat than current climate models have predicted.

Mixed support for multilateralism to achieve sustainability

In 2015 all 193 UN member states signed up to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), just as a little later in the year they signed up to the Paris Agreement on climate change. SDG 17, Partnerships for the Goals, committed states to revitalising global partnerships for sustainable development.

Each country’s tangible rather than rhetorical commitment to working together is measured with the Index of Countries’ Support to UN-Based Multilateralism (UN-Mi) which assesses six indicators:

- Ratification of major UN treaties – the more the better.

- Percentage of votes aligned with the international majority at the UN General Assembly each year – the more the better.

- Participation in selected UN organisations – the more the better.

- Participation in conflicts and militarisation – the fewer the better.

- The use of unilateral coercive measures – the fewer the better.

- Contribution to the UN budget and international solidarity – the more the better.

The major findings in 2024 are that:

- The majority of the world’s population lives in countries with moderate to high levels of support for multilateralism.

- The average UN-Mi score is 65 and the median is 70 (out of 100).

- Barbados, Antigua and Barbuda, and Uruguay scored more than 90.

- Only 10 countries scored less than 50 and only 5 less than 45.

- Bottom of the list with a score of 16 was the USA – support for the Rules-Based Order, anyone?

Here is an illustrative sample of countries’ scores:

Rank Score (%)

27 Philippines 83

72 New Zealand 75

75 Indonesia 75

120 China 67

136 PNG 64

157 Australia 60

160 UK 59

185 Russia 49

190 Israel 29

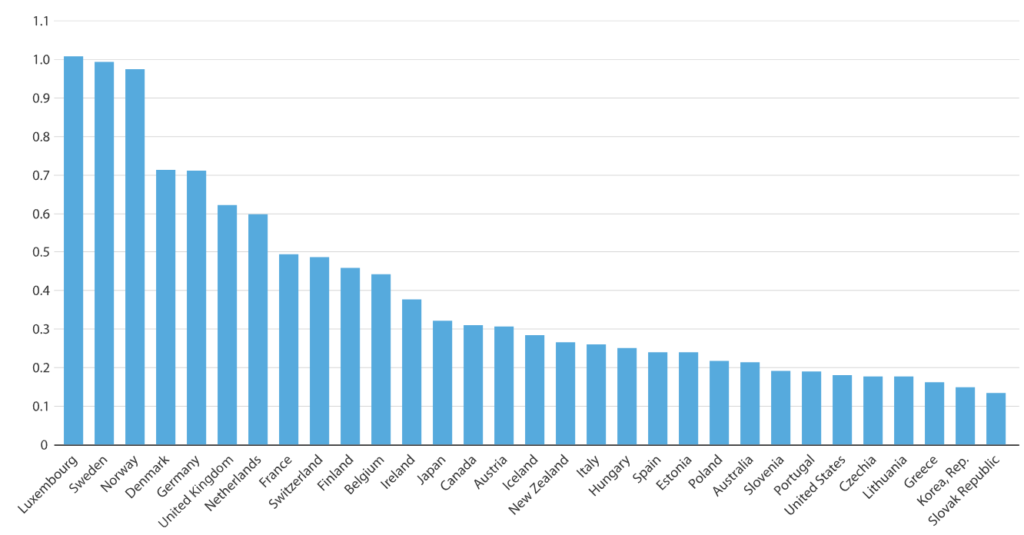

Our own performance is ‘OK’ but leaves a lot of room for improvement. To illustrate, we scored the maximum on major UN treaties ratified but not quite so well on UN human rights treaties ratified (7 of 9). Less favourably, there were 10 instance of Australia’s use of unilateral coercive measures and a dreadful performance on development assistance where we spent 0.2% of our national income between 2018 and 2022 compared with the internationally agreed target of 0.7%:

The report concludes that:

‘Effective UN-based multilateralism is more important than ever before. No nation can solve the global climate crisis on its own. No nation can make a low-cost energy transition on its own. No nation can ensure peace and security on its own. No nation by itself can protect the vital ecosystems or avoid the potential dangers and pitfalls of runaway technologies. Collectively, new funding mechanisms must be identified to channel the world’s global savings to sustainable development investments, based on countries’ needs and commitments to achieving the SDGs, and to safeguard the global commons.

Nation-states, which remain at the heart of the multilateral system, must be held accountable for upholding the values and principles of the UN Charter and implementing the SDGs – the shared global vision for sustainable development.’

Improving our score might be a useful strategy for strengthening Australia’s bid to hold the 2026 COP meeting - I’m not overly concerned about our ranking, it’s the score that really matters. I’ll be pleasantly surprised, however, if any Commonwealth government minister or senior official has even read the report.

Petrol v Electric correction

Apparently, the hyperlink to the video referred to below on 15 September 2024 dropped off somewhere along the way. Apologies, I’ll try again:

‘A nice video compares the environmental impact of internal combustion engine cars and EVs.’

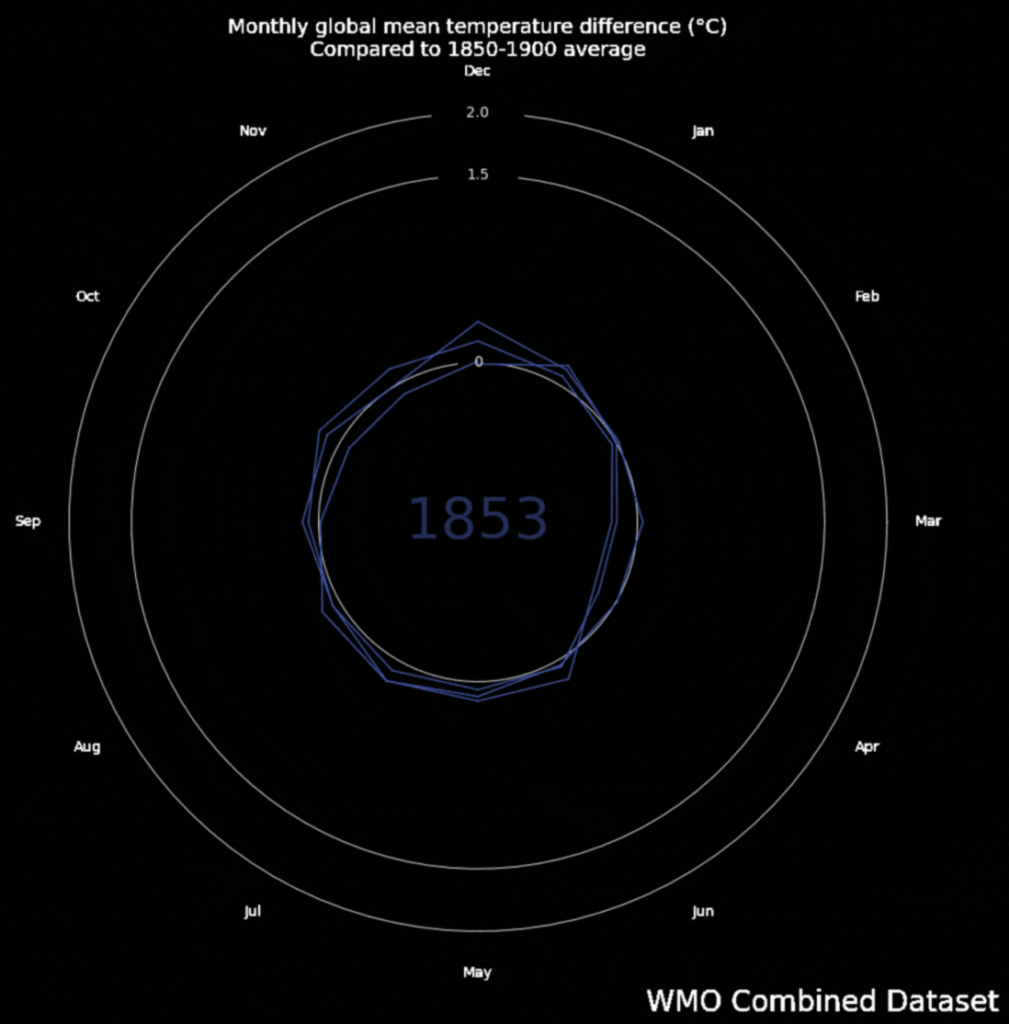

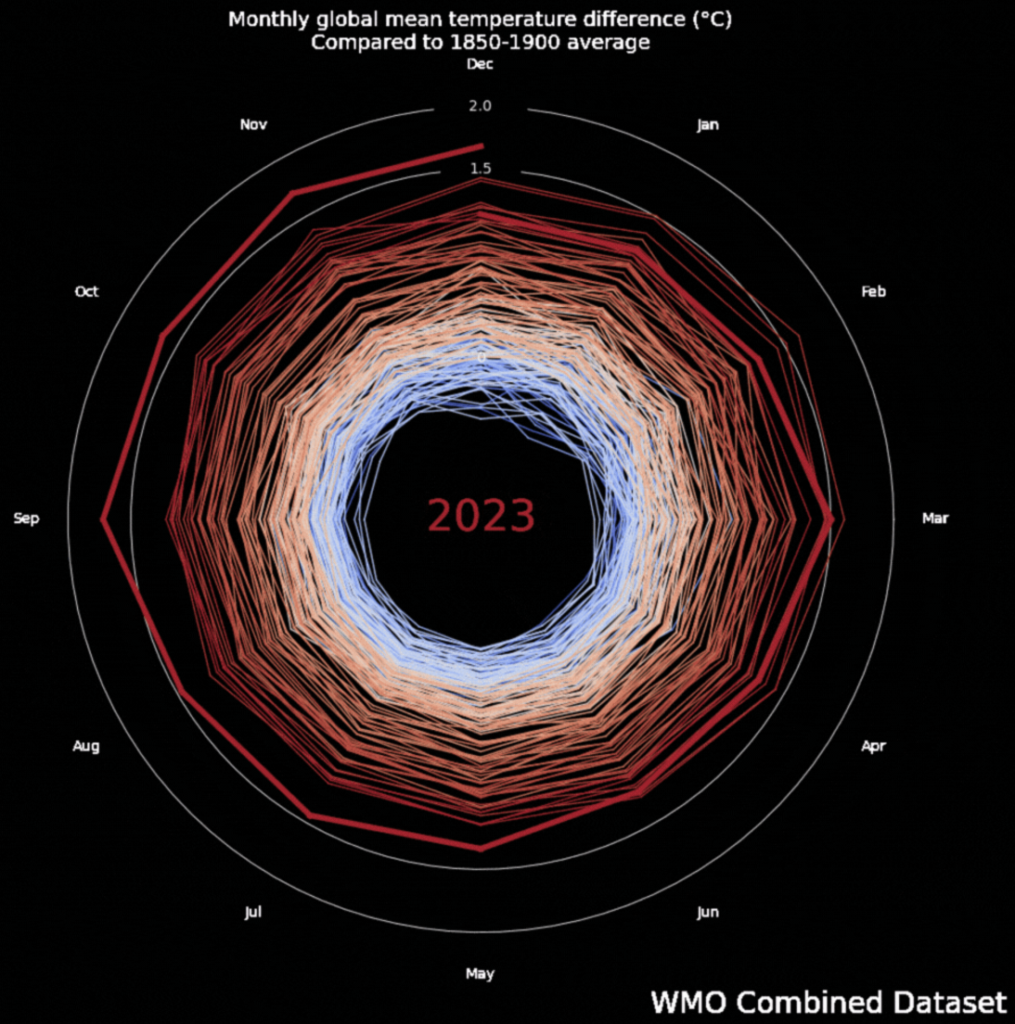

A relentlessly warming world 1851-2023

The two stills below are from the beginning and end of a 10-second animation showing monthly global temperatures since 1851, compared to the average for 1850-1900. The overall change is abundantly clear from the stills but it’s worth watching the 10-second animation to see the relentless progressive change over the 170 years and the greater speed of warming in recent years.