Environment: Australia publishes its first climate risk assessment

April 6, 2024

Australia is conducting its first climate risk assessment and developing an adaptation plan. Not only humans experience heat stress, so do other animals and plants. If you must feed wild birds, listen to the experts tips.

Assessing Australias climate risks

The Commonwealth Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) has released the National Climate Risk Assessment. First pass assessment report. Before considering the contents of the report, it should be noted that:

- DCCEEW claims that this is Australias first National Climate Risk Assessment. I suppose that if you capitalise National Climate Risk Assessment, that may be strictly true. But if you remove the capitals, this is not the first assessment of risks posed by climate change to Australia. That honour goes to a report that Anthony Albanese asked the Office of National Intelligence to prepare soon after coming to office, and in line with an election promise, that examined security threats posed by global heating. The report was completed last year but despite pressure from the Greens in parliament, Albanese has refused to release it. Maybe hes worried it will give Chinas National Meteorological Administration some information they can use against us next time we have a cyclone.

- The subtitle, First pass assessment report, indicates that following this rapid risk assessment a more in-depth, second pass risk assessment is now underway and due to be completed later in 2024.

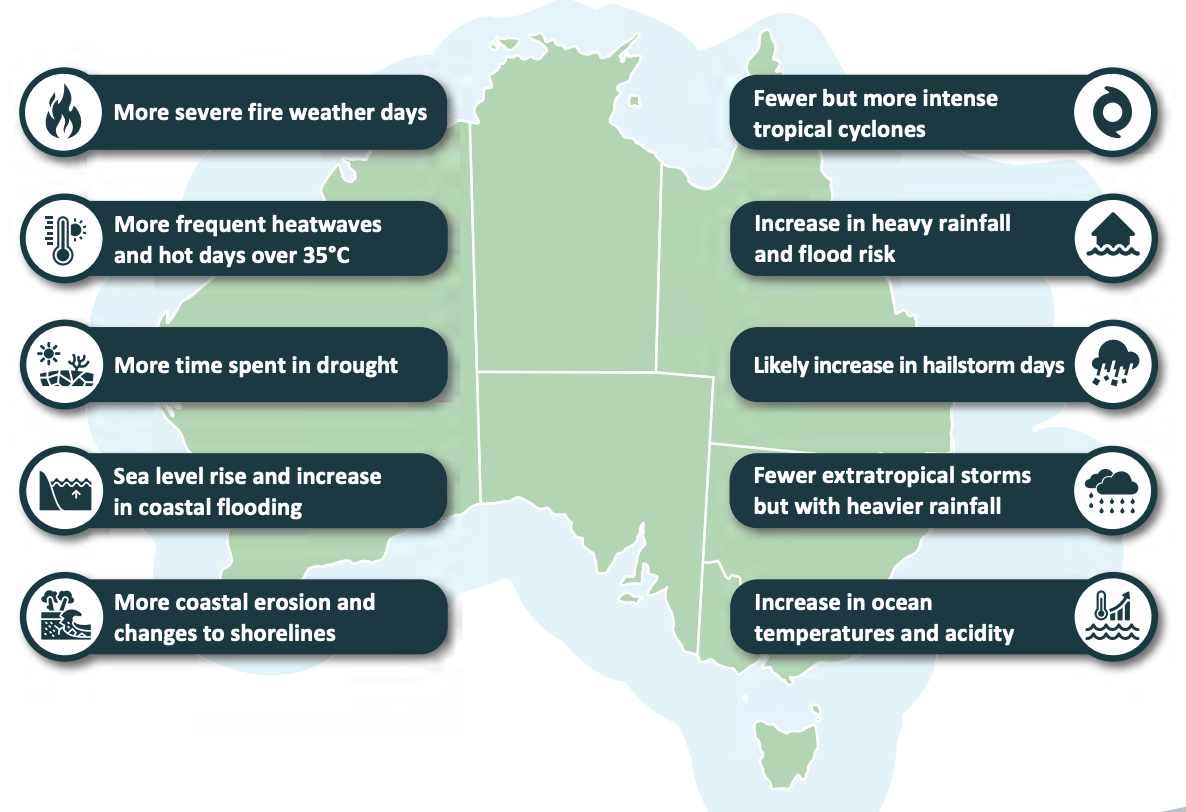

The purpose of the whole assessment is to help governments, industry and communities prepare for, adapt to, and mitigate risks from a more challenging climate. Credit here to the Albanese government for (1) initiating what should have been started about twenty years ago and regularly updated since, (2) accepting that climate change will continue to exacerbate risks (even after we reach zero emissions), and (3) focusing on the ten priority hazards projected by the Bureau of Meteorology to worsen in coming decades:

To assess the risks, the report considers low and high emissions scenarios leading to average global warming of 1.5oC and 2oC in 2050 and 2oC and 3oC in 2090, recognising that temperatures around Australia are likely to be higher than the global average.

The first pass report discusses 56 nationally significant climate risks across seven systems (security, economy, health, infrastructure and built environment, natural environment, primary industries, regional communities). The report on an eighth system, First Nations values and knowledges, is not yet complete.

For the second risk assessment, 11 of the 56 risks have been prioritised for detailed consideration in both 2050 and 2090. Four of the 11 are recognised to be cross-system risks and the second pass will explore complex risk and cross-system dependencies. This sounds good but I was disappointed not to see any mention of using the concepts and methods of complex systems thinking in the second phase and the adaptation plan. Experience tells me that government and private sector managers tend to think of systems in terms of bureaucratic departments, hierarchical organisation charts and protection of their own empires. Exploring cross-system problems usually involves establishing an interdepartmental working group that meets for a year and then peters out.

The challenges we face in Australia and globally from climate change (and not only climate change) require an appreciation of self-organising natural systems, the components of which are interdependent and continuously influencing each other, and other systems, in complex, often unpredictable, ways. Concepts and tools are available to help people understand, analyse, work in and change such systems and it would be nice to see the government adopt such a systemic approach to managing climate change.

A detailed National Climate Risk Assessment report will be released on completion of the second pass assessment. This will inform a National Adaptation Plan to reduce climate risk and ensure Australia can continue to prosper in an increasingly climate-disrupted future. If youd like to make a submission to the Issues Paper for the Adaptation Plan, youd better get your skates on as the consultation period finishes on April 11th.

What is telling about the assessment report and issues paper is that the government clearly understands the underlying problem and the serious risks posed to Australia by climate change. Also, that they have a pretty good idea already of what needs to be done to manage as best we can the inevitable consequences.

I think its fair to assume that they also know what needs to be done to tackle the fundamental causes of climate change. What they seem as incapable as their predecessors of doing is take real action to reduce and eliminate greenhouse gas emissions. Albanese and colleagues are an enormous disappointment in this regard.

Temperature thresholds of life

Currently, about 35% of the global population is chronically stressed by heat. This is projected to increase to 45-75% this century. Over a similar period, the area of global land affected by deadly climate conditions will increase from 12% to 45-70%.

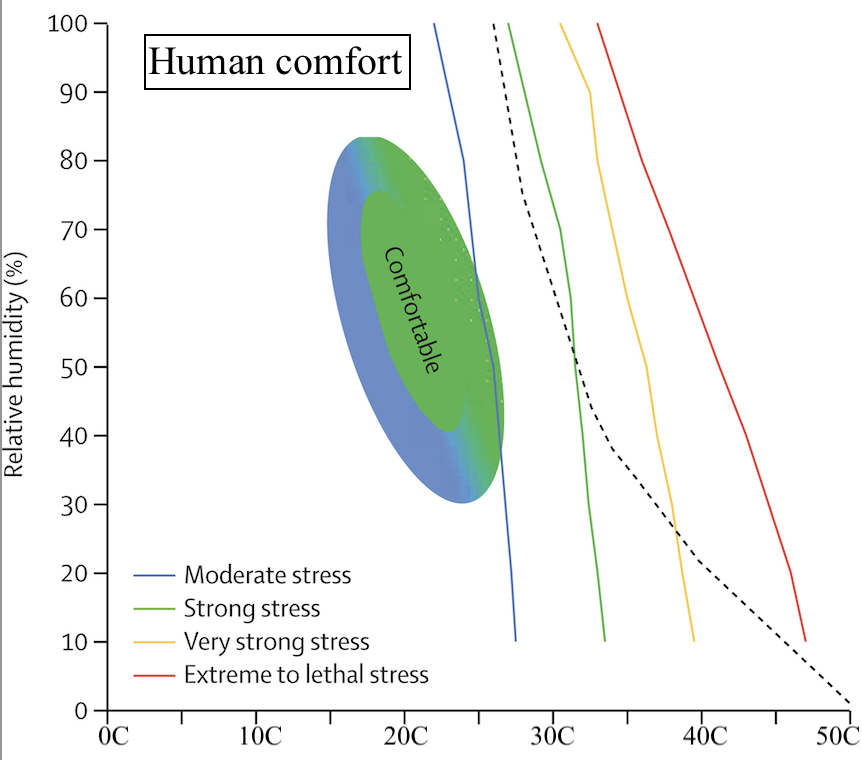

A comfortable temperature range for humans is 17-24oC, lower when relative humidity is high, higher when its low, but it is also dependent on many personal and local factors and the duration of exposure. At very high humidity and 31oC, an exposure time of six hours can be dangerous.

The figure below shows the comfortable range for humans and how heat stress increases as the temperature increases, reaching potentially lethal levels at 30-45oC depending on the humidity. As a rule of thumb, the level of stress jumps up a notch for every 5oC increase in temperature above 25oC. In essence, the levels of temperature, humidity, wind and radiation and the frequency and duration of heat waves are the significant environmental influences on heat stress in humans.

It’s not only humans who suffer. Heat stress causes reduced growth of farm animals resulting in lower yields and reproductivity, and death at very high temperatures. Not surprisingly considering our common ancestry, the comfort ranges for cattle, pigs and poultry are similar to humans. Many of us also remember the two-day heatwave in November 2019 that killed 23,000 spectacled flying foxes (a third of the Australian population) in northern Queensland.

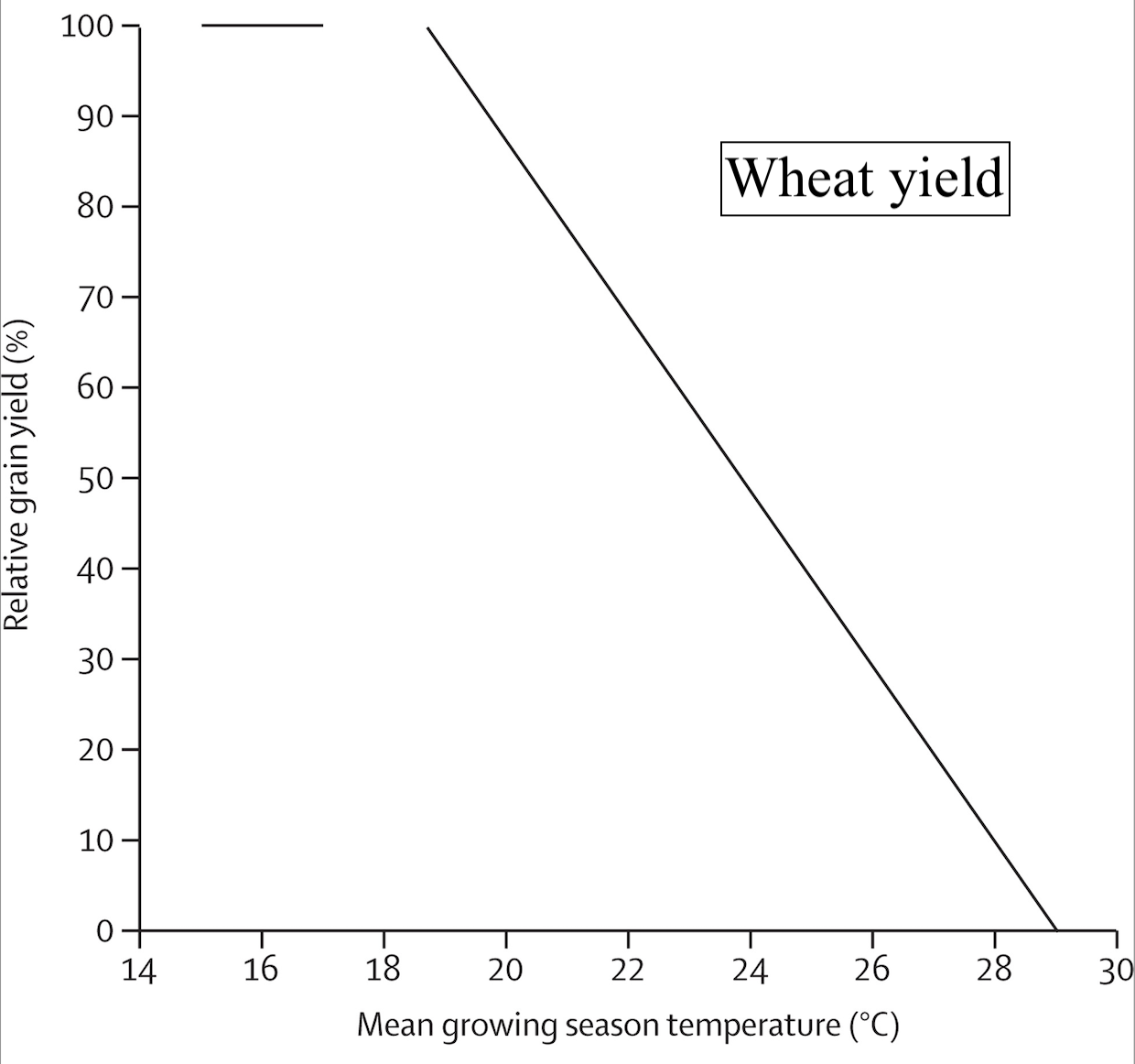

Nor is it only animals that are affected by heat. Single events of extreme heat can, of course, devastate crops but prolonged heat stress is also harmful. In a field experiment involving irrigation and artificial heating, the wheat yield decreased steadily once the average temperature of the growing season exceeded 18oC, with complete crop failure at 29oC.

Continued global warming is inevitable and strategies are needed to help humans, other animals and crops avoid and manage short-term and prolonged exposure to heat. One hopes that this sort of information is being fed into the Climate Risk Assessment.

Happiness across the world

This is a bit outside my usual ambit but lately Ive been banging on about how bad things are socially and environmentally in Sub-Saharan Africa, with little prospect of improvement in coming decades. A recent report of levels of happiness across the nations of the world strongly suggests that conditions in Sub-Saharan Africa are affecting the mental wellbeing of the residents.

This is illustrated in the graphs below that compare the happiness levels (measured on a scale of 0-8) in Western Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa at different ages during 2021-23. The happiness level in Western Europe is 2.5-3 points higher across the age range. Interestingly, theres little differences between the sexes (females red; males green) in either place

Happiness is a slippery matter to define and measure and researchers have been examining what makes people more and less happy, and whether any changes last, for decades. This study focused on the national levels of six potential influences on happiness: GDP per capita, healthy life expectancy at birth, having friends and relatives that can be relied on, freedom to make life choices, generosity (making donations to charity), and perceptions of government or business corruption. All were statistically related to happiness in the predictable directions and its not difficult to see why happiness levels in Sub-Saharan Africa might be (with South Asia) the lowest in the world. The results might have been even worse if it had been possible to include national measures of peoples optimism about the future.

Just out of interest, the four happiest countries are in Scandinavia (scores around 7.5) and the least happy countries (scores of 2-3) are united by poverty and conflict rather than geography, with Afghanistan clearly at the bottom of the table. Australia is ranked tenth with a score of 7.06; this is 0.27 lower than in 2006-10. About 70 countries reported improved happiness between 2006-10 and 2021-23, some by 1-2 points, quite a lot on a scale of 0-8.

Dont be an outdoor worker in Florida

Florida lacks any state-wide protections for outdoor workers. A recent attempt to require certain employers to implement an outdoor heat exposure safety program died in a state Senate committee. The legislature has now gone one step further and approved a bill that prohibits local governments from establishing heat protections for outdoor workers. Luxuries such as access to water and shady places for rest breaks and training in heat illness and first aid are clearly early signs of a socialist takeover.

There are also no federal protections for outdoor workers against heat in the USA and only three states have formal heat protections for outdoor workers. Predictably, all are on the notoriously left leaning west coast: California, Oregon and Washington.

Feeding wild birds

Feeding wild birds is discouraged by the experts because it causes malnutrition, disease and unbalanced populations. Notwithstanding that, many Australians do it regularly, not just for their own pleasure but also because they think its helping the birds. Practising acceptance, Birdlife Australia has produced a guide to limit the damage. In summary:

Do not give birds bread, crackers, mince, raw meat, honey, sugar, avocado, citrus fruit, onions, garlic.

Better bird foods are commercially-produced bird nectar mix, fresh fruit and vegetables, seeds, nuts, grains, earthworms, insects. Put out a variety of foods in different locations and clean up and replace food daily.

Better still, plant a bird-friendly garden containing native species that provide food, safety from predators and breeding habitat.

During hot and dry periods, it is more important to provide cool, clean, fresh water in safe places. You might even be lucky enough to get Powerful Owls to visit for a drink and a bathe as in this video.