Environment: Biodiversity is decreasing but damaged ecosystems can be restored

August 12, 2023

Agricultural intensification is killing European birds. Europeans are killing Australias native rodents. Getting rid of invasive species and reintroducing native species can re-establish natural ecosystems.

Agricultural intensification is killing birds

Among terrestrial vertebrates, birds contain the most species. Unfortunately, there is strong evidence that in many places around the world species have been lost and population numbers have fallen. Many reasons have been proposed and studied to try to determine the causes of these declines but we still do not have a good understanding of how pressures created by humans are affecting bird populations.

Further light has been shed on this by a study of the population numbers of 170 common bird species at more than 20,000 sites in 28 European countries between 1980 and 2016. The study focused on quantifying the influence of four anthropogenic causes of pressure on bird numbers: agricultural intensification (in particular pesticide and fertiliser use and the creation of larger farms), changes in forest cover, urbanisation and temperature change.

Over the period (just 36 years remember), there has been a 25% decline in bird numbers overall, but with considerable variation across countries and bird types. Most affected have been woodland birds (decline of almost 60%) and species living in the colder north (40% decline).

The major influence on declining bird numbers was agricultural intensification which was associated with population reductions in 31 species and increases in 19. The most negative effect of intensive farming was observed, not surprisingly, on farmland and woodland species and on species that have an invertebrate-rich diet during the breeding season or that migrate long distances.

The second strongest killer was urbanisation, with 12 species experiencing population declines and 9 species increases. Farmland and grain- and invertebrate-eating species were the most negatively affected.

Temperature change was associated with equal numbers of species experiencing an increase (hot area dwelling, urban dwelling and woodland birds) and a decrease (especially cold dwelling species and long-distance migrants) in population numbers.

Changes to forest cover were associated with more population increases (16 species, especially long-distance migrants) than decreases (9 species).

The authors conclude that their study provides strong evidence that agricultural intensification is the dominant cause of declining bird numbers and suggest that the fate of common European bird populations depends on the rapid implementation of transformative change in European societies, and especially in agricultural reform. Europe wont have any woodland birds soon if urgent action isnt taken.

While the details may differ in Australia, its reasonable to believe that the overall picture is fairly similar. Regrettably, 22 bird species have already been driven to extinction since 1788 and many are currently in danger. With two additions occurring in July, there are now 154 Australian birds on the Governments List of Threatened Species.

Apex predators come in all sizes

Mention apex predators and minds conjure up images of majestic and somewhat frightening sharks, wolves, lions, crocodiles and eagles. But sea gulls?? Perhaps when they steal food from the plates of inattentive, urban alfresco diners but surely not in the wild.

Hawadax Island, about 24km by 6km, is in the Aleutian Island Archipelago, Alaska. It was invaded by Norway rats in the late 18th century and by Arctic foxes in the next. The once common breeding seabirds, shorebirds and land birds on Hawadax were soon eliminated and as a result the ecosystem of plants and animals that lived in the rocky intertidal areas was destroyed.

Move on a couple of centuries and the foxes were eradicated in 1984 and the rats in 2008. Five years post rattus, many of the land, shore and marine birds were returning to the island a pattern observed on many other islands where invasive mammals have been removed. Less well studied, however, is if and how long it takes for communities of species (ecosystems) to recover to their pre-invasion status.

Five years after the eradication of the rats, there was little recovery of the intertidal communities on Hawadax Island i.e. they still looked like islands with rats. Eleven years post-eradication, however, the intertidal communities were looking more like those on islands without rats. That is, the populations of many of the invertebrate herbivore grazers (e.g. limpets and snails), other invertebrates (e.g. anemones, mussels, sponges and sea stars) had decreased and ground cover by fleshy algae had increased. Also greatly increased were gulls and oystercatchers.

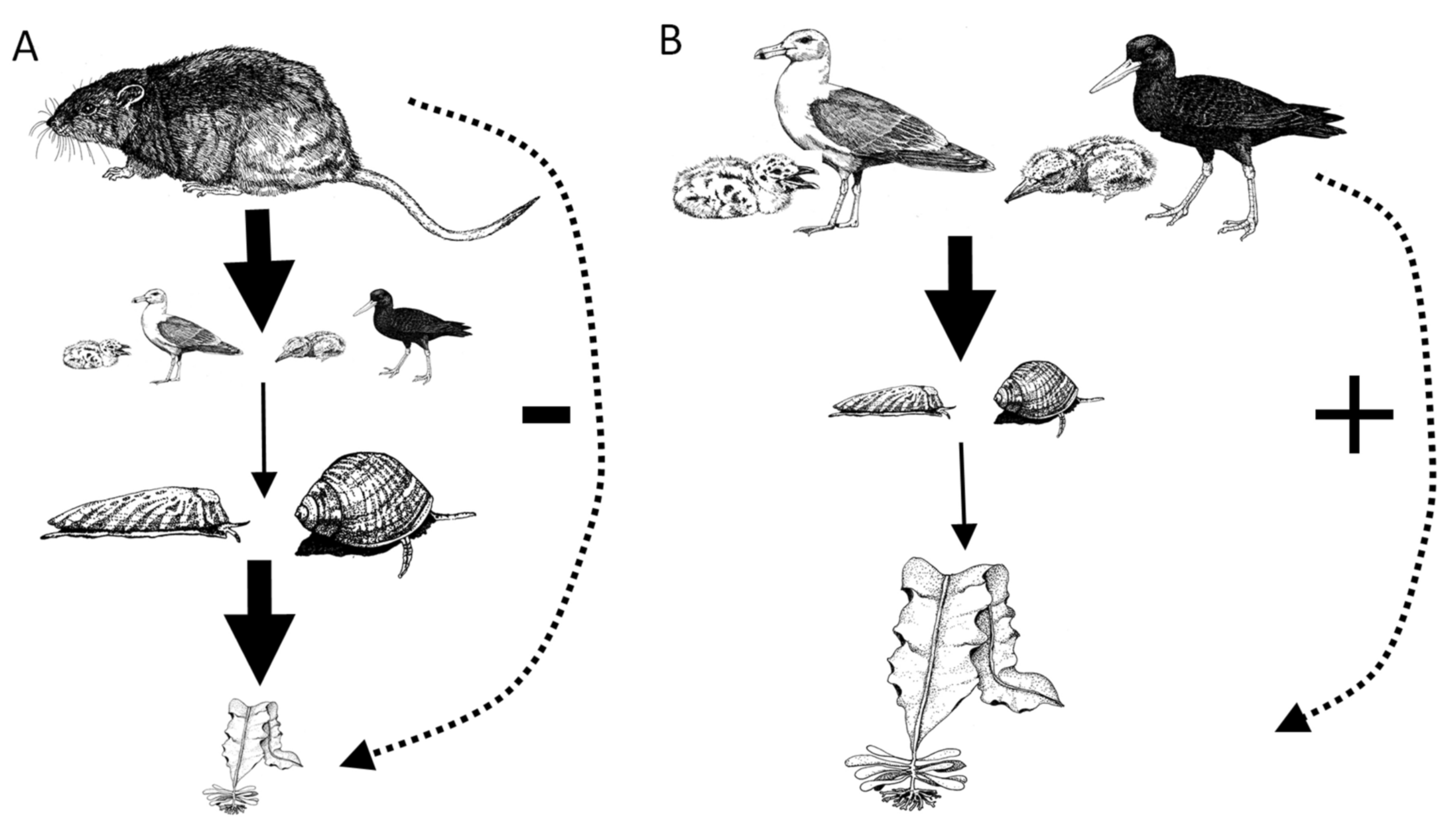

The explanation for this is that before the rat invasion the shorebirds were the apex predators on the rocky intertidal areas (Figure B below). They controlled the populations of the invertebrates, including those that eat fleshy algae. The scientists call this a three-trophic level ecosystem (birds eat invertebrates that eat algae).

But once the rats appeared, they became the apex predators (Figure A), the shorebirds were eliminated, the invertebrates became dominant, the algae were greatly diminished, and the whole intertidal ecosystem changed.

Although it took a while for the ecosystem to start to return to normal, whats ten or twenty years in the great scheme of things. The good news is that if you remove the invasive pest, passive recovery of the natural community can occur quite quickly.

On reflection, I suppose a gull probably does look big and scary to a snail.

Why have Australian mammals gone extinct?

Since 1788, Australia has lost 34 terrestrial mammals. Theres no doubt that habitat destruction, invasive species, inappropriate fire management regimes, new diseases, hunting and, more recently, climate change have played a part in these losses. However, was the arrival of Europeans simply the final nail in the coffin of species that were already on the decline before Captain Phillip landed? - perhaps as a result of the increasing population size and practices of Indigenous Australians, the appearance of dingoes or even natural selection. Or has European colonisation destroyed previously thriving species of mammals?

If a now extinct species was already on the downward spiral before 1788, youd expect to see reduced genetic diversity in specimens collected prior to and during its numerical decline. On the other hand, good genetic diversity before and during the decline indicates that the course of extinction was extremely rapid and likely attributable to European settlement.

Australia has more than 60 species of native, placental rodents (e.g. stick-nest rats, mice, including hopping mice, rock rats and tree-rats) found nowhere else. They arrived here, probably over land, from New Guinea about 5 million years ago. Unfortunately, rodents feature particularly prominently in our list of extinctions 11 mainland species have been lost since 1788 and many that remain are highly endangered.

A study of early museum specimens of 8 extinct rodents and their 42 living relatives found no evidence of reduced genetic diversity around the time of their disappearance. This indicates (1) that the populations of the now extinct species were large before 1788 and that their declines began, and were rapid, following the arrival of Europeans, and (2) that while large, stable populations with good genetic diversity can protect species against some environmental changes, it is no insurance when the changes are dramatic and multiple.

One piece of good news is that the extinct (last seen in 1895) Goulds mouse is no longer extinct. The study demonstrated that it is the same species as the not-extinct Shark Bay mouse that is now restricted to one island in Shark Bay, WA. Before 1788, the Shark Bay (or is it Goulds) mouse was widespread across Australia, so maybe it can be again in time.

In another piece of good news, the threatened Dusky hopping mouse has been discovered on the Australian Wildlife Conservancy property at Scotia between Broken Hill and Mildura. This is 100km from its previously closest confirmed location - in recent times, that is. The Dusky hopping mouses range has contracted greatly since European colonisation.

Just for contrast, previous studies have shown that the Tasmanian tiger and mainland populations of the Tasmanian devil were already seriously compromised before 1788.

Mukarrthippi Grasswren

The Mukarrthippi Grasswren, a subspecies of Striated Grasswren found only in a small area of Murray Mallee in central NSW, is one of the birds recently classified as Critically Endangered. This is the category on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species that immediately precedes Extinct in the Wild.

Mukarrthippi (pronounced moo-kwah-tippy) comes from the language of the Ngiyampaa people and can be translated as small bird of the spinifex (Mukarr). The names of over 40 species and subspecies of Australian birds are inspired by Indigenous languages, including Budgerigar.