Environment: Carbon bombs will explode all hopes of 1.5

July 22, 2023

There are over 400 fossil fuel projects each with the potential to release more than 1 Gt of CO2. Serious environmental and human rights problems associated with mining the energy transitions essential metals. Barry Commoner described the problem and its cause 60 years ago.

Carbon bombs

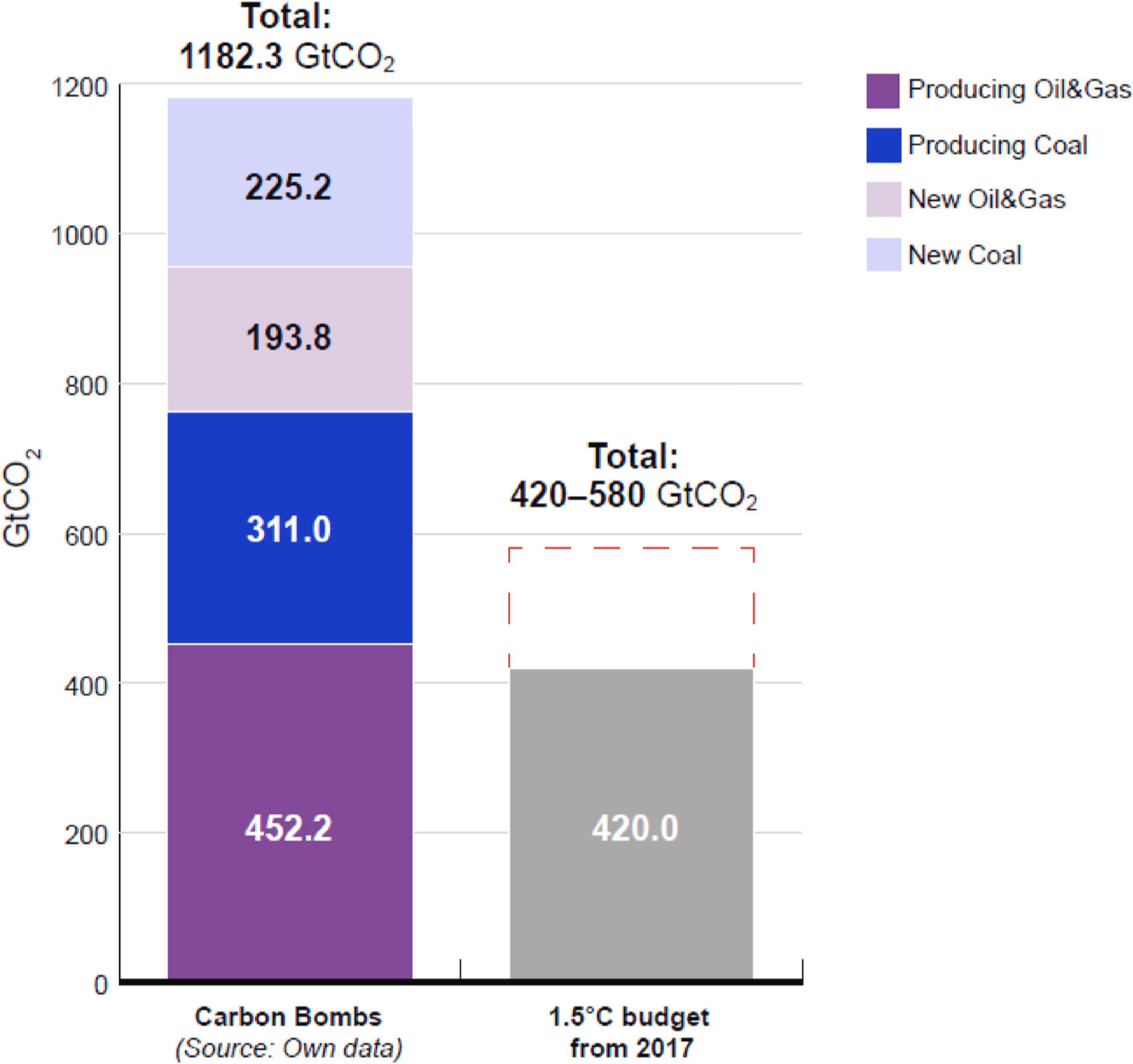

There are 425 existing and proposed fossil fuel projects globally that have the potential to release more than 1 Gigatonne (Gt) of CO2 during their operating lives. Despite even the International Energy Agency recommending that no new fossil fuel projects should be opened if we want to keep warming under 1.5oC, companies are still developing, and governments are still approving, new mines and fields. In fact, 40% of the 425 carbon bombs have not yet started production. While coal may be considered to be on the way out, there are more coal mines than oil and gas projects on the list of all carbon bombs (230 and 195 respectively) and on the list of bombs still being developed (93 and 76).

The emissions potential of the 425 carbon bombs is roughly double the remaining carbon budget for staying under 1.5oC. If we were to abandon the projects that have not yet started to produce coal, oil or gas, we would eliminate over a third of the total emissions potential of these projects.

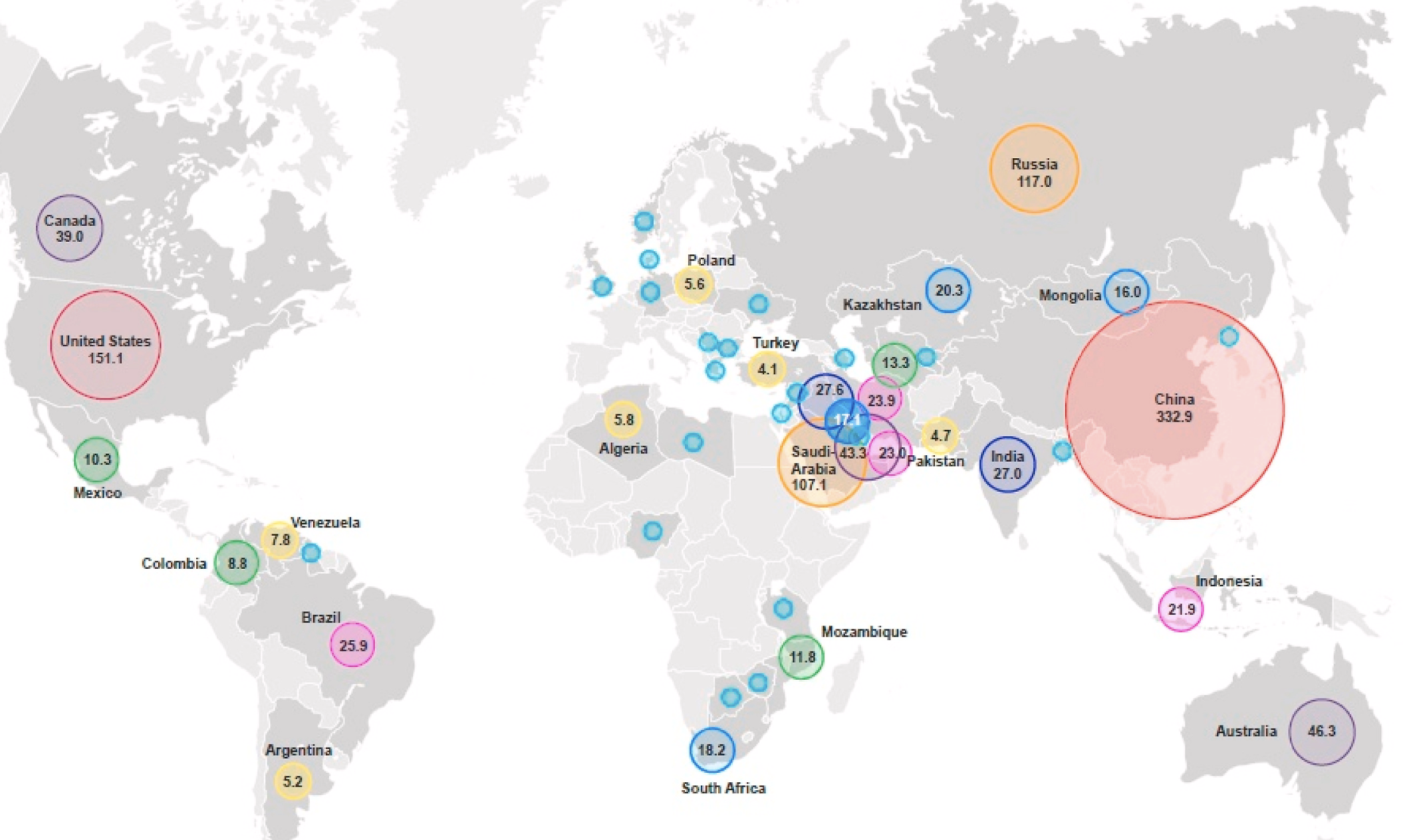

The map below shows the 48 countries with at least one carbon bomb and the combined emissions potential of each countrys bombs. China, USA, Russia and Saudi Arabia lead the way with a combined total of approximately 60% of the total potential emissions. Australia is home to 23 of the bombs, 20 of which are coal projects and 12 of which are new. The BHP-Mitsubishi Red Hill Coal Project in Central Queensland and the Goldwyer Shale oil and gas project in the Canning Basin in WA are each expected to produce about 4.5 Gt of CO2 during their lifetimes.

The policies of governments of fossil fuel producing countries, including Australia under current and past administrations, continue to encourage companies to increase the supply of fossil fuels. They justify this by reference to consumer demand, whether that be domestic consumers or overseas governments. It is, however, clear that we will not make the progress needed to control global warming without reducing supply.

As the researchers say, Defusing carbon bombs will be essential for keeping temperatures below 1.5 warming and new strategies are needed for designing effective measures that will result in their non-extraction - an area so far neglected by mainstream mitigation policy. Our list of carbon bombs brings much clarity to the question of where the climate crisiscan be addressed from the supply side. The list can assist activists and policymakers alike in setting priorities and preparing the next step of defusing carbon bombs.

Rare earth metals

A few years ago most people wouldnt have had a clue what rare earth metals, commonly referred to as rare earths, are, never mind able to name any. There is now, though, a vague awareness that there are numerous previously unheard of elements with exotic, almost unpronounceable names (e.g. Praseodymium, Ytterbium and Gadolinium) that are for some mysterious reason essential for our mobile phones and more generally the energy transition (e.g. for superconductors, ceramics, batteries, magnets).

Despite their name, the 17 rare earths arent that rare in the Earths crust but finding their minerals in mineable concentrations can be challenging. In 2022, about 300,000 tonnes of rare earth minerals were mined globally, China being responsible for 210,000 of those. Next in line was the USA with 43,000 tonnes and then Australia with 18,000.

Total world reserves of rare earth minerals are estimated to be about 130 million tonnes. China holds about a third and Brazil, Russia and Vietnam hold half between them. Australia, which likes to think its a big player in mining for the transition, has only about 4 million tonnes.

Three significant points emerge out of all this for me:

- Mining for the rare earths and other elements (e.g. copper and cobalt) that are essential for the energy transition is often extremely harmful to the natural environment, not least because it is often conducted in remote places in countries with little or no environmental regulation by organisations that dont care, possibly in collaboration with corrupt governments.

- For similar reasons, mining is often associated with extreme violence and gross abuses of the human rights of Indigenous people, local communities (particularly women) and mine workers.

- It is unrealistic to expect developing, often very poor, countries to be able to improve mining practices on their own and it is callous in the extreme for rich countries to turn a blind eye to the abuses so long as the supplies keep flowing. Indeed, blind eye is probably an inappropriate metaphor for what is often active collaboration by western companies.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is a source of various valuable minerals (e.g. copper, cobalt, tantalum, tin, gold, diamonds) other than the rare earths. Conditions in the DRC are particularly dire but are illustrative of the dangers associated with extractive industries in developing countries, some of which, such as the DRC, are riven by violent conflict. I doubt that many P&I readers are nave enough to believe that the conflict experienced in countries such as the DRC is caused entirely from within. As the linked article makes clear, the governments, financial capital and military-industrial complexes (particularly the arms industry) of many western nations are heavily involved in the underlying causes and the perpetuation of the problems.

Closer to home, there are serious environmental and human rights issues in the nickel mining industry in Indonesia.

Australias under-reported fugitive methane emissions

Fugitive emissions of methane from Australias coal, oil and gas industries are just over 80% higher than the reported emissions. These are the emissions that occur during the mining and production process and have nothing to do with burning the fuel to produce power. In percentage terms the underreporting is greater for oil and gas (92%) than coal (81%) but in absolute terms (million tonnes of CO2 equivalent) the underreported methane emissions are much higher in the coal industry. The total under-reporting of almost 28 MtCO2e is equivalent to about 6% of Australias total (reported) annual greenhouse gas emissions.

The implications of this are threefold:

- Measurement and reporting of fugitive methane emissions must be dramatically improved;

- Greater effort must be put in to rapidly controlling and reducing fugitive emissions of this very potent greenhouse gas;

- To meet the cumulative emissions ceiling of 1,233 MtCO2e in the governments revised Safeguard Mechanism, the companies covered by the Mechanism would need to increase their reduction of emissions from the currently required (but inadequate) 4.9% to 9.8% per year, more than halving their emissions in seven years.

According to a recent International Energy Agency report (Tackling methane emissions from oil and gas operations is one of the most important measures to limit near-term global warming they say), Australias oil and gas-related methane emissions are estimated at 1 Mt per year and we would need to spend $0.75 billion over the next seven years to deliver a 75% fall in energy related methane emissions by 2030. That would become almost $1.5 billion if the 80% under-reporting in the previous report were taken into account.

Frankly, I wont be holding my breath for any of the required corrective actions to happen.

Commoner sense isnt that common

As a biologist, I have reached this conclusion: we have come to a turning point in the human habitation of the earth. The environment is a complex, subtly balanced system, and it is this integrated whole which receives the impact of all the separate insults inflicted by pollutants. Never before in the history of this planet has its thin life-supporting surface been subjected to such diverse, novel, and potent agents. I believe that the cumulative effect of these pollutants, their interactions and amplification, can be fatal to the complex fabric of the biosphere. And, because man is, after all, a dependent part of this system, I believe that continued pollution of the earth, if unchecked, will eventually destroy the fitness of this planet as a place for human life. I believe that world-wide radioactive contamination, epidemics, ecological disasters, and possibly climatic changes would so gravely affect the stability of the biosphere as to threaten human survival everywhere on the earth.

Barry Commoner. Science and Survival (1966)

If the environment is polluted and the economy is sick, the virus that causes both will be found in the system of production.

Barry Commoner. Making Peace with the Planet (1992)

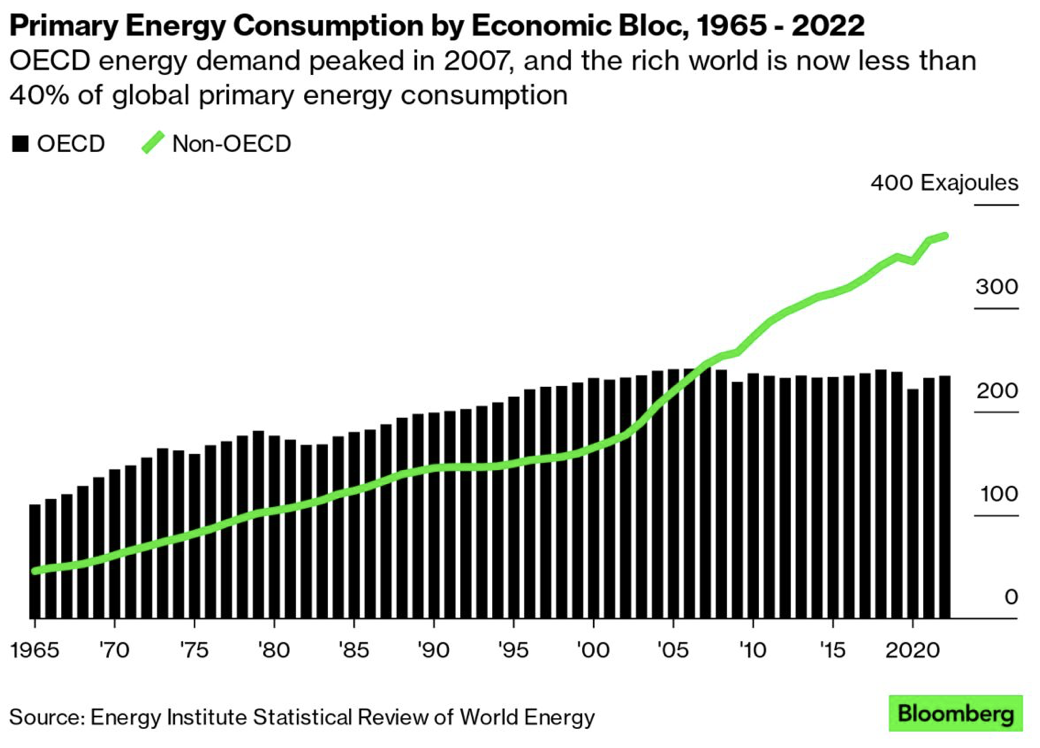

Poorer countries consume 60% of world energy

New data spotlight high energy demand in developing economies. OECD energy demand peaked in 2007, and the rich world is now less than 40% of global primary energy consumption says Bloomberg News. Phew, I dont need to worry about my energy use then!!

Hang on a minute, the 38 countries of the OECD which collectively consume the 40% contain only 17% of the worlds population.