Environment: CO2 emissions still increasing

May 19, 2024

CO2 emissions continued to increase in 2023 with now little chance of global warming staying under 1.5oC. Planting trees is part of the solution but only in the longer term. Even Hollywood is getting the message.

Plants are part of the (long-term) response to climate change

In the Autumn 2024 edition of the magazine of the Friends of the Botanic Gardens of Sydney, Chief Scientist Professor Brett Summerell provides very clear guidance for maximising the contributions that plants can make to managing climate change.

The most important thing societies can do is stop clearing native vegetation and trees. This will reduce global warming, lessen the impact of any particular level of warming and halt the loss of biodiversity. Ecosystems containing old growth forests and woodlands store more carbon and contain more habitat for wildlife than young forests. This is not new knowledge but politicians seem to have more trouble absorbing it than trees have absorbing carbon.

Large scale planting of trees to absorb and store CO2 in the trunks, branches and roots can be effective but only if it is done properly. It takes time, say 10-20 years, for new plantings to have any noticeable effect on the carbon cycle, longer if there is a drought. Summerell highlights the Global Biodiversity Standard for ensuring that new plantings really do capture carbon and promote biodiversity: plant a diversity of tree species that are both native to the region and free of pathogens, use seeds from a variety of sources to develop genetic diversity, and provide ongoing care and maintenance.

There are many good reasons to plant and preserve trees in urban areas. They are particularly necessary for reducing the urban heat island effect and providing habitat for wildlife but they are unlikely to capture much carbon.

Summerell takes a chainsaw to a range of harmful, useless, expensive, wasteful, greenwashing practices. Chief among these are monoculture plantations of cheap, fast growing, non-native trees that lack genetic diversity and do little for biodiversity. The ‘plant it and walk away’ approach is more about gaining tax exemptions than solving environmental problems. Unfortunately, eucalypts are frequent unwitting parties in this approach.

Summerell concludes that plants can be part of the solution to climate change but it won’t be simple or quick and it requires expertise and investment. In the short term the answers lie elsewhere, ‘we need to hasten our move to renewable sources of energy and reduce our general footprint on the planet’.

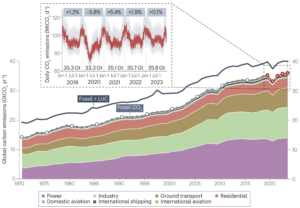

Global CO2 emissions still rising

Worldwide emissions of CO2 increased slightly in 2023, principally as a result of continuing long-term increases from electricity generation, industry and land transport (the sectors that are also the largest emitters).

In 2021, the IPCC stated that, starting from a 2020 baseline and assuming no temperature overshoot, for a two-in-three (66%) chance of keeping global warming under 1.5oC the world could afford to emit a further 400 Gt CO2 (‘the carbon budget’). During the four years of 2020-2023, 157 Gt CO2 were emitted into the atmosphere. At this current rate of emissions (and there’s no reason to assume emissions are going to fall rapidly anytime soon), the world’s carbon budget will be exhausted in 6 years (the beginning of 2030).

The carbon budget for a five-in-six (83%) chance of staying under 1.5oC will be exhausted even sooner, in late 2027. These are better odds of avoiding disaster but still equivalent to playing Russian roulette with our children’s lives.

How consistent are experts’ projections?

Knowing how difficult it is to make accurate projections doesn’t stop governments, think tanks, self-appointed experts, lobby groups, researchers, etc. making them. Nor does knowing how unreliable they are stop journalists, commentators (including me) and axe-grinders reporting them.

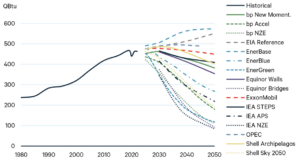

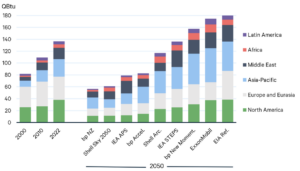

Notwithstanding the problems, it’s my observation that when different people who know what they are talking about (this is the crucial factor) make projections about the same thing, there is usually a reasonable degree of agreement amongst them. But not always, as illustrated by four of the comparisons by Global Energy Outlook of scenario-based projections made by a range of agencies about the world’s energy future to 2050

- What will happen to global fossil fuel demand?

The projections are all over the place, principally depending on what governments do about it.

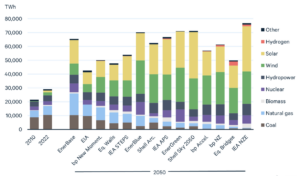

- What about the global demand for electricity?

A bit better. Everyone agrees that demand is going up, that coal and natural gas are on the way out, and that solar and wind are set to become the main generators of electricity by 2050. Nevertheless, the projected increase in demand still varies by a factor of almost two.

- Global demand for natural gas?

Not everyone agrees that natural gas is doomed (music to the ears of the Commonwealth and several state and territory governments). Some people think usage will be cut by more than 50% over the next 30 years and some think it will grow by 25%. But note that the most optimistic projection still involves burning a massive amount of gas.

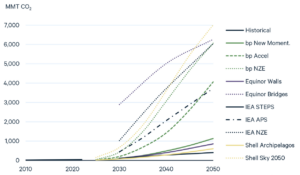

- Is carbon capture and storage finally going to succeed?

How would you know? In 2022 42 million tons of CO2 were captured (0.1% of CO2 emissions). In 2050 it might be anywhere between 500 and 7,000 million tons.

In a nutshell, these four comparisons are not very reassuring. Perhaps the main takeaway message is that it always pays to read the small print about how the projections were made. Putting incompetence and outright lying aside, many of the differences between various soothsayers are likely the result of each one using different assumptions, data sources and models to construct their projections, although even this benevolent interpretation doesn’t rule out malicious deception.

That all said, imagine how different the world would be if we all accurately knew what the future holds.

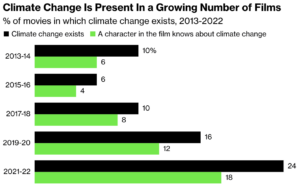

Hollywood responds to climate change

In 2021/22 a quarter of the most popular movies included some mention of climate change and in almost a fifth a character in the film knows about climate change. This represents a four-fold increase in both measures since 2015/16.

Activists know that stories are often more useful than facts for educating and motivating the public. The increasing portrayal of climate change in popular culture is also an indication that the problem is now sufficiently mainstream for the industry to feel comfortable that there’s profit to be made from portraying it and for audiences to feel comfortable with it as entertainment. I’m not entirely comfortable with either of these propositions.

The linked article also provides a list of ten movies, TV shows and books that include interesting climate themes. The Day After Tomorrow is referenced in the article but not included in the ten!

Bug Hunt

Can you name any of these insects? Have you seen any of them lately? Do you know which ones are native and which are invasive?

Starting at the top left and going clockwise, they are:

Western yellow jacket wasp - loves crashing picnics and BBQs.

Harlequin ladybird - found right across Australia apart from the tropics.

Gypsy moth - causes deforestation, like several other invaders from the northern hemisphere.

Giant honeybee - workers can grow to 2cm in length.

Large earth bumblebee - nests in burrows in the ground. Found only in Tasmania.

Red dwarf honeybee - often hitches a lift on ships from Asia.

And, of course, they are all invasive species - some of them are well established here.

If you’d like to improve your native and invasive bug identification skills and help scientists keep track of all sorts of bees, ants, wasps, etc. across Australia, you can join the online Bug Hunt. All you have to do is download the iNaturalist app, take a snap of any bugs you see and upload it to the app. You’ll be told what the bug is and if it’s an unwanted one you’ll be helping to control it. Kids will love it. Short explanatory videos are on the Bug Hunt website.

Short-lived climate-pollutants

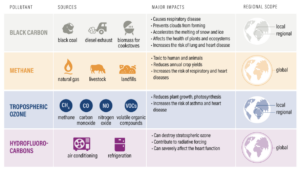

I think most readers understand that methane is a much more potent greenhouse gas than CO2 but that because it remains in the atmosphere for a much shorter period its heating effect is much less than CO2 in the longer term.

There are also a few other ‘short-lived climate pollutants’, all of which have a much lesser warming influence than CO2 or methane but which are nonetheless worthy of action to reduce their emissions, particularly in the short-term when every 0.1oC of warming that we can avoid makes the world a marginally safer place for us and for most other species.

Black carbon is airborne particulate matter (think visible and invisible dirty fumes) released when fossil fuels are burnt. Tropospheric ozone is ground level ozone produced by chemical reactions between other air pollutants. Hydrofluorocarbons are used in air conditioning units and fridges.

As the table above demonstrates, these short-lived climate pollutants have harmful effects on human health, plant growth and the environment over and above their climate warming effects, providing additional reasons for governments and communities to require polluters to mend their ways.

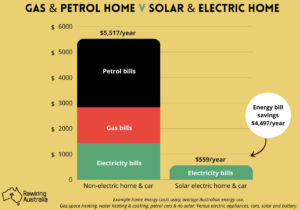

Save money, the environment and humanity

Who could turn down a deal like that? And it’s simple to do: make all your home appliances and cars electric.