Environment: eating responsibly - less bottled water and even less meat

June 30, 2024

Bottled water is not good for the environment or your health. If you eat meat, eating less is good for both. Governments are unreliable protectors of forests and human rights (but you knew that already).

Bottled water, an unnecessary luxury

The global market for bottled water has expanded enormously in recent decades – 73% in just the last decade. Bottled water is often seen to be healthier, taste better and be more convenient than tap water, and in some places some or all of those are no doubt true, but aggressive marketing has also played a large part in its growth. PepsiCo, Coca Cola and Nestlé are the big players, having cornered 20% of the global market.

Each year the world consumes 350 billion litres of bottled water (I think that’s about a sixth of the tap water Australians use every year), worth $410 billion. The Asia-Pacific region consumes half of that and North America almost a third. Africa consumes only 2% of the market.

Australians are also major consumers. We are fifth in the list of total consumption per year (about 13 million litres, but well behind the USA’s 61 million) and second in consumption per person at 500 litres per year – who’s drinking 450 of mine?

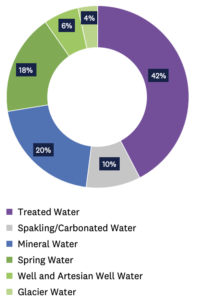

There are two main types of bottled water: treated and natural. The pie chart below for 2021 shows market volumes of ‘tap-like’ bottled water for these categories and sub-categories. The chart excludes products with added minerals, flavours and supplements which, somewhat surprisingly, represent a small portion of the market, as does sparkling water.

The source of ‘treated’ bottled water, which need not be specified and is generally not highlighted in its branding, may be a natural source or a public supply system. Whatever the source, it is often purified or processed in some way. Treated water constitutes 42% of the market for bottled water by volume.

‘Natural’ bottled water, the source of which should be specified, is further divided into two. ‘Natural mineral water’, often referred to simply as ‘mineral water’, comes from groundwater sources. ‘Other natural water’ comes from wells, springs and glaciers. Mineral water and spring water account for two-thirds of the volume of ‘natural’ water sales. One alleged attraction of each particular brand of natural water is its distinctive taste, mineral composition and purity.

While bottled water is often thought to be cleaner than tap water, hundreds of brands have been found to be contaminated with inorganic and organic impurities, including microbiological organisms, at various times.

Withdrawal of water from natural sources for bottling, although small in volume compared with irrigation, can deplete local groundwater springs and affect local public water supplies, tourism and agriculture. In the French alps, Danone extracts 10 million litres (four Olympic pools) per day for Evian. Additionally, each litre of bottled water consumes 2-4 litres of water during its production. In the Global South, the withdrawal of water for bottling contributes to water stress in already water-depleted areas and impacts the achievement of several of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

One million plastic bottles are sold globally every minute, generating about 25 million tonnes of waste per year, most of which goes into landfill.

Bottled water is here to stay, one suspects, but one can’t help feeling its use is mostly an unnecessary luxury, particularly when one in three people globally lacks convenient access to any safe, clean water. Governments should be placing a higher priority on ensuring that all people in the world have convenient access to clean water (and efficient sanitation), and reducing the environmental damage done by the water bottling industry. This is what they agreed when they signed the SDGs in 2015.

Eat less meat but better meat but what is ‘better meat’?

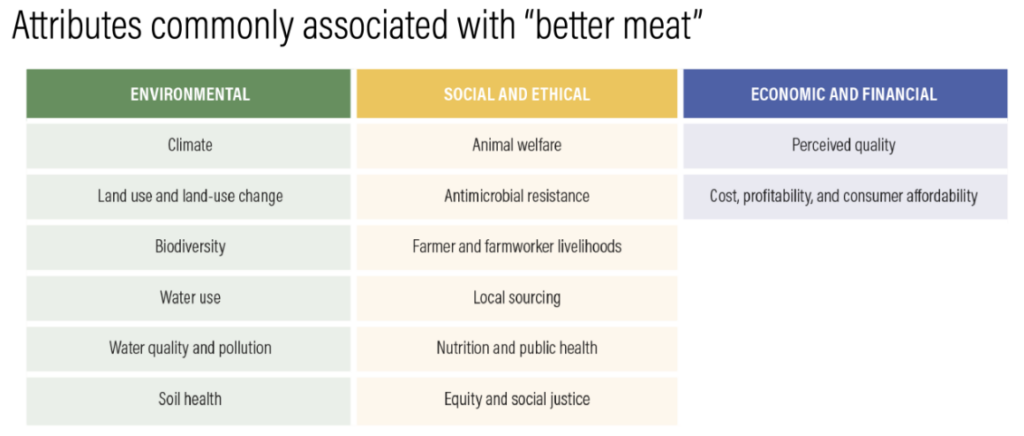

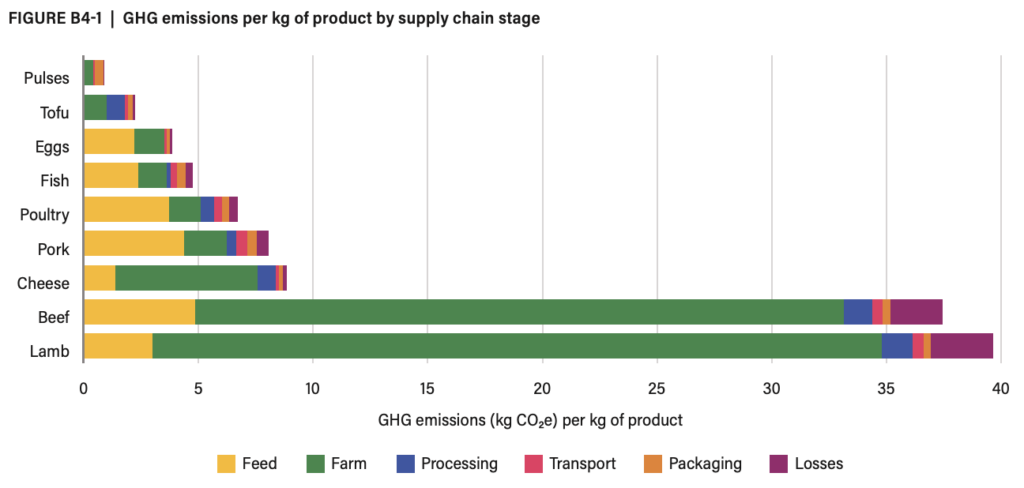

The production of meat, especially beef and lamb, is associated with enormous greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, massive deforestation and poor animal welfare. But those are not the only concerns people have about eating meat:

It’s complicated though because meeting one attribute doesn’t always align with meeting others. Better for the planet may not be better for the animals. For instance, chicken has relatively low GHG emissions but many birds, often kept in very poor conditions, are required to produce one ton of protein. Beef, on the other hand, has high emissions but requires very few animals, again often kept in poor conditions, to produce a ton of protein.

There are also variations in the way particular meats are produced. For instance, grass-fed cattle grow at a slower pace, emit more methane during their lives and may require more land than conventional grain-fed cattle which are fattened in feedlots in their final months.

Generally speaking, ‘alternative’ animal production systems are associated with higher emissions and more land use per kilogram of protein produced than conventional systems, especially for beef and lamb. Alternative systems also use more freshwater and discharge more phosphate into the environment.

To reach the best trade-off among the various factors, concerted action across policy makers, producers, food companies and consumers is required to improve production and consumption practices:

- Know the Scope 3 (downstream) emissions associated with all food stuffs produced, distributed and consumed.

- Shift production, distribution and consumption to lower emissions foods, especially plant-based foods – better for the climate, nature, animal welfare and possibly human health. See, for instance, the Danish government’s strategies to support the green transition in agriculture and food which includes an Action Plan for Plant-based Food, a Strategy for Green Proteins and Plant-Based Food Grants.

- Examine not just the type of meat but also how it is produced.

- Where a product has high environmental impacts, eat less of it. If you are already eating less meat, for example, why not eat even less but better meat, particularly beef and lamb.

There is, however, one caveat to these recommendations: they apply much more to wealthy western nations than developing ones.

One final point: consuming locally produced meat makes almost no difference to the GHG emissions because transport accounts for only 1% of beef- and lamb-related emissions. That’s not to say there aren’t other good reasons to be a locavore.

Protecting Tallaganda native forest

I’ve written several times over the last 9 months about the disgraceful intention of the NSW government to log in the Tallaganda State Forest and the actions of community groups that have, so far, thwarted those ambitions. Please watch this 6-minute video about Tallaganda to be reminded of the beauty and intrinsic value of our native forests and why it is so important and effective for ordinary folk to stand in the way (physically on occasions but also with citizen science and lobbying elected representatives) of the bulldozers, chainsaws and politicians.

Over recent months, conservationists have been working at night to identify and map Greater glider den trees in the Tallaganda State Forest. Greater gliders build their dens in the hollows of big old trees. Once a den tree is found, logging cannot occur within 50 metres. That is why it is vitally important that the den mapping is done diligently. This usually means by volunteers rather than the agencies responsible for the logging. If you think this comment is a little harsh on loggers, please read about the thoroughly shocking treatment of ecologist Mark Graham by NSW government authorities, including police officers, and forestry contractors.

Can take away coffee cups be recycled?

Can you put slightly food-stained pizza boxes in the recycling bin?

Test your knowledge about recycling with a dozen questions in the Woollahra Council Recycle Right Quiz. Of course, your local council may have somewhat different rules, so best to check on their website as well.

I find it very frustrating that many of my neighbours clearly don’t care one jot about recycling or they care in principle but can’t be bothered to do it correctly. However, I am also frustrated by how complicated it is. As an example, if you do the quiz, you’ll see that disposable coffee cups are not recyclable in my council’s system. I checked with my local council about take away cups that have a claim to be recyclable printed on them. The very helpful Environmental Education Officer informed me that although such cups may well be recyclable in principle, the sorting system can’t identify and separate these cups from non-recyclable cups in comingled recycling materials. Hence, they shouldn’t go in the recycling bin.

Some shopping centres and store chains have their own cup recycling programs but they depend on the facility itself sorting them into a separate ‘waste’ stream that then goes to a dedicated cup recycling program.

I’m absolutely convinced that we’ll only get good recycling rates when the sorting is done automatically after collection, not by people before collection. How many different ‘waste’ streams can members of the public and organisations cope with? Adherence to the rules would improve, however, if the bin men (I don’t believe I’ve ever seen a bin woman) left any bins containing wrong materials unemptied. This happens where my sister lives in England, as I learnt to my messy inconvenience some years ago when I didn’t listen carefully enough to her instructions.

Life can be tough in the forest

The photo below was taken during one of the night-time surveys in the Tallaganda. It shows a Powerful owl with a freshly killed Greater glider and demonstrates the value of identifying glider dens for the protection of both of these threatened species as well as our native trees.