Environment: Expert calls Australia’s carbon offset scheme a scam

April 21, 2024

Australia’s carbon offset scheme costs a lot and captures almost no carbon but provides a fig leaf for continuing emissions. Technology-based Carbon Dioxide Removal is still a distant dream. Distributed energy resources can be the Swiss Army knife of the electricity system.

Australia’s carbon offset scheme exposed as a scam

Over the last decade the Australian government’s national carbon offset scheme has encouraged the development of projects to help us reduce our net carbon emissions. In simple terms, the government issues a credit to a project proponent for each tonne of CO2 that would be in the atmosphere had it not been for the project. The proponent can then sell the credit to a CO2 polluter who has exceeded their limit on pollutions or even back to the government – one credit currently sells for $30-35. The government’s Clean Energy Regulator expects to issue at least 20 million credits in 2024.

The most popular type of project involves converting a relatively bare patch of agricultural land into a permanent, evenly-aged forest of native trees using only natural regeneration – i.e., no artificial seeding or planting. This might be facilitated by reducing grazing pressure from stock and feral animals, stopping native plant clearing and managing non-native plants. The technical name for this activity is Human-Induced Regeneration or HIR. (I should note that no new HIR projects have been accepted since October 2023 but the existing ones continue to operate.)

Real success of offset projects such as this is, of course, completely contingent on projects being given credits only for real, additional and permanent increases in the carbon stored in the soil and vegetation in the project area.

Andrew Macintosh and colleagues have studied 182 HIR projects in Australia (largely in WA, NSW and Queensland) to examine their success in establishing forest and woody cover where there was previously none. This is intended to determine the amount of CO2 that has been drawn out of the atmosphere and stored in the vegetation and soil.

The results are truly disgraceful but not at all surprising to anyone who has been following the carbon offset story:

- There was only a small increase in forest cover (3.6%) and a negligible increase in combined sparse woody and forest cover (0.8%) across the 3.4 million hectares covered by the 182 projects (equivalent to about 40% of Tasmania). Trends in forest and woody cover in the credited areas largely mirrored fluctuations in comparison areas, suggesting that the changes were largely not additional to what would have occurred anyway, presumably because they reflect rainfall variability rather than responses to project activities.

- Despite this, 27 million carbon credits were issued to the projects during 2013-22. In fact, 23 million credits were issued to projects where woody cover declined or was largely stagnant.

- Making matters worse, the Australian Government has spent about $300 million purchasing credits from the projects and is contractually committed to purchase a further $1.2 billion.

Issuing low integrity credits can lead to worse climate outcomes because offsets are a permission to pollute. When the credited abatement is not real, additional and permanent, offsets can enable an increase in emissions from a polluter with no offsetting emission reduction elsewhere.

According to the authors, the root cause of the integrity issues with the projects is that many credited areas have been in areas where native vegetation has not previously been comprehensively cleared, where the capacity to permanently increase forest carbon stocks is generally likely to be small, and in arid areas where it is difficult to separate the impacts of project activities from rainfall-induced changes.

MacIntosh and colleagues are very critical of the lack of transparency in the scheme. Proponents have not been required to publish any offset or audit reports and if they do any voluntary measurement of biomass changes, they are not required to publish any information about that either.

These results suggest that the scheme is a sham and that many of the projects are scams. Unfortunately, there is little likelihood that this evidence will lead to any substantive changes. The CO2 emitters are very happy to buy credits to let them keep polluting - the cost is just a business expense. Those selling the credits are very happy to keep making money for doing nothing. The pollies of both major parties are happy to use the myth that the scheme works to claim that they are doing something.

Macintosh and two colleagues published a scathing, non-technical version of their paper in a recent edition of The Saturday Paper, while cartoonist David Pope lampooned offsets with reference to net zero murders:

Carbon Dioxide Removal – will it scale up in time?

Climate scientists and politicians are agreed that if we are to limit global warming to 1.5 or even 2oC at the end of this century, it will be necessary at some point to remove large quantities of CO2 from the atmosphere, not only by increasing the coverage of trees, mangroves, kelp, grasslands etc. to increase photosynthesis, but also by using technology to draw CO2 directly out of the air, i.e., Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR).

There is a variety of CDR methods available at present and they are already being used commercially so that greenhouse gas emitters can buy carbon credits to offset their emissions (offsetting is very popular!). However, the scale of removal must increase dramatically to have any effect on the 1.75 trillion tonnes of CO2 that we have pumped into the atmosphere in the last 250 years (and that’s excluding emissions from land use change).

So, a few snapshots of CDR in 2023 to give you a sense for where we are at and the magnitude of the challenge.

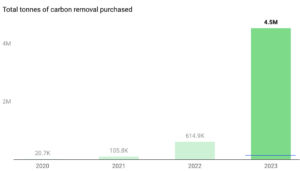

The tonnage of CO2 removal purchased by companies to offset their own emissions is increasing rapidly and reached 4.5 million tonnes (Mt). The big increase between 2022 and 2023 was mainly due to Microsoft purchasing 2.67 Mt to be delivered over 11 years from Ørsted who will use Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) to do the work.

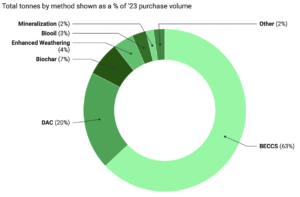

The most popular CDR method for purchases is BECCS (63%), not surprising in view of the Ørsted-Microsoft deal. This is followed by Direct Air Capture (DAC – 20%) and a field of also-rans. The average price across all methods was A$750 per tonne, although it varied by a factor of 15 across methods. Biochar and BECCS were at the lower end of the price range: A$200 and A$460 per tonne respectively.

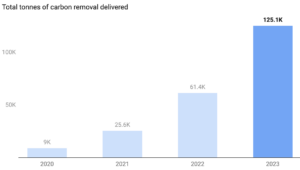

Actual CO2 removal from the air is also increasing annually but still reached only 125,000 tonnes (Kt) in 2023. The horizontal blue line in the 2023 column of the ‘CDR purchased’ histogram above represents the amount of CO2 captured that year. It is claimed that the average time between purchase and delivery is three years (that seems incredibly optimistic to me – happy to be corrected).

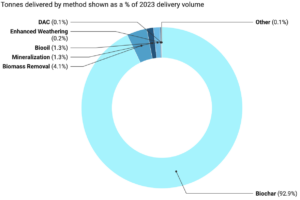

When we look at the method that removed most (of the not very much) CO2 removed in 2023, there is only one horse in the race: Biochar at 93%.

Whether CDR is on track to deliver the needed 4-5 Gt of CO2 removal by 2050 is impossible to say. But remember that would be just 10% of current annual emissions, and let’s not forget the nearly 2 trillion tonnes that will be scooting around in the atmosphere by then.

Distributed energy resources

Distributed energy resources (DER) are technologies, such as rooftop solar, home battery units, EV batteries and smart, flexible demand appliances that generate and/or store electricity in households and businesses. According to Dr Gabrielle Kuiper, ‘DER is the Swiss Army knife of the electricity system. Not only can it provide generation, storage and flexible demand, but when coordinated, it can provide network services, emergency power supplies and ancillary services to support the whole electricity system. We are only beginning to understand its potential’.

Added to which, this cutting-edge technology could deliver accumulated economic benefits to Australia’s energy system of more than $19 billion by 2040, as well $10 billion of benefits to consumers. But this won’t happen on its own. Policies are needed to stimulate research, roll-out and integration, and make DER an equal partner with large scale electricity generation and transmission in the energy system.

Serendipity goes extra-terrestrial

Don’t get me wrong, I think it’s immensely impressive and important when a scientist discovers a new butterfly in Peru … but discovering 49 galaxies (not stars or exoplanets, but galaxies indeed) in less than three hours, that has to take the biscuit. Especially if new galaxies weren’t even what you were looking for. But that’s exactly what five astronomers did when they went looking for hydrogen gas in one far-distant galaxy with a radio telescope.

I find it difficult enough to comprehend one galaxy. Our own Milky Way, by no means exceptional as galaxies go, contains several hundred billion stars and is 100,000 light years across. How do you make sense of numbers like this? Never mind that there might be two trillion galaxies in the universe! I can say it but I can’t really imagine it.

On top of which, galaxies sometimes collide (I wonder if there’s a cosmic NRMA offering insurance for that) and, according to the discoverers of the ‘49ers’, ‘in one case, a galaxy is stealing gas from two companion galaxies and using it to fuel its own star formation’. Mind boggling!

The astronomers didn’t find any hydrogen in the galaxy they were originally searching, by the way. They must be bitterly disappointed.

Afghanistan on the edge

A couple of weeks ago I highlighted that Afghanistan is the least happy country in the world. The photograph below was taken by Ebrahim Noroozi and is a finalist from Asia in the 2024 World Press Photo Contest.

‘Since the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021, an already war-devastated economy on the verge of collapse continues to be impacted by the withdrawal of foreign aid. A four-year drought and two major earthquakes have exacerbated the crisis. The UN estimates that 97% of Afghans live below the poverty line and the number of displaced people has topped six million.

The jury felt this powerful, human-centred story demonstrates how photographers can show the realities of intersecting crises.’

‘Children stare at an apple that their mother brought home after begging, in a camp for internally displaced people in Bagrami, on the outskirts of Kabul.’

By the time you read this I’ll be away on holiday. My Sunday contributions will return on May 19th.