Environment: hole in the ozone layer: the patient is improving but still needs intensive care

July 28, 2024

The hole in the Antarctic’s ozone layer is recovering but very slowly. How to eat seafood sustainably, restoring our disappearing mangroves and cemeteries for the living.

Has the hole in the ozone layer been fixed?

I was puzzled by a headline in the New York Times that read ‘A Global Push Fixed the Ozone Hole. Satellites Could Threaten it’. Although the Montreal Protocol of 1987 has succeeded in phasing out the use of about a hundred ozone-depleting chemicals (ODCs), I wasn’t aware that the hole had been ‘fixed’. So, what’s really going on?

Thanks to Prof. Google, this is what I now understand the story to be:

- The ozone layer sits 15-30km above Earth’s surface. The ozone is produced by natural chemical reactions in the stratosphere. Without the ozone layer, animals and plants would be scorched by harmful ultraviolet radiation. For instance, humans would suffer more skin and eye damage and more cancers, and crops would be reduced.

- Measurements in the 1970s and 80s identified a general ‘thinning’ of the ozone layer due to a reduced concentration of ozone. Manufactured ODCs (mainly the chlorofluorocarbons used in fridges, air conditioners, spray cans and insulation materials) were recognised as the cause. It was also observed that the thinning was more pronounced over the Antarctic and the concept of a ‘hole’ in the ozone layer became popular.

- However, it is not a real hole, devoid of all ozone, like the centre of a doughnut has no dough. Rather, it is a greater reduction in the concentration of ozone in the layer above the Antarctic as a result of the meteorological conditions over the south pole. Only there, and only at a certain time of the year, does the ozone concentration fall below a limit that scientists then refer to as a ‘hole’.

- The ‘hole’ appears every year between about August and December because the coming of spring in the southern hemisphere leads to a thinning of the ozone layer all around the world which is more pronounced over the Antarctic.

- The hole closed relatively late in December in 2023 (see this 40-second animation) and there is speculation that climate change may be affecting the ozone layer, but that’s another story.

- The internationally agreed Montreal Protocol has been very successful at eliminating the use of ODCs. Consequently, the concentration of chlorofluorocarbons in the atmosphere peaked in the 1990s. It remains high, however, because some of the ODC gases remain in the atmosphere for several decades and when old appliances break down they release more ODCs. Also, while the concentration of ozone in the layer has stopped falling, its increase is very slow.

- So, yes, the ozone layer is slowly restoring itself. However, globally it is not expected to return to its 1980 level until 2040, and over the Antarctic not until the 2060s.

Hole fixed? Not really or at least not yet. But it is a rare example of concerted international cooperation that has stopped an environmental rot and set us on the road to solving the problem. Compared with halting and reversing climate change, however, fixing the ozone layer and its hole is child’s play.

If you’d like more detail about the ozone layer and the hole, I recommend a 7-minute video from NASA.

Four tips for a sustainable seafood diet

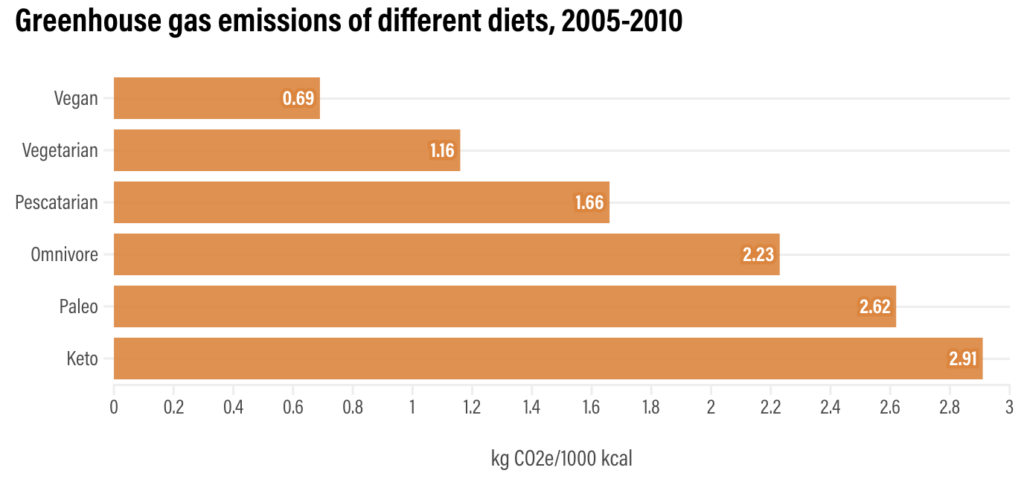

It isn’t always easy to know what is best (or least bad) for the environment food-wise. A pescatarian’s diet has about 50% more greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions than a vegetarian’s and 25% fewer than an omnivore’s. So it’s half-way good.

But the seafood supply chain is fraught with other environmental problems. In the wild, most commercial fish populations are seriously depleted, and many mammals, amphibians, birds and other fish die in trawlers’ bycatch. Where fish farming occurs, habitat damage, pollution and disease outbreaks are common. Then there are the human rights abuses on some countries’ fishing fleets and fish farms.

Here are four tips to help you choose and eat seafood more sustainably:

- Eat species with a lower environmental impact. Just eating seafood is a good start, with wild fish having about a twentieth of the GHG emissions of beef. But it’s not just about GHGs. For instance, bottom trawling is notorious for destroying the seabed and the feed for farmed fish has a high carbon footprint. Species with low GHG emissions include seaweeds, oysters, mussels and small fish from the sea such as herrings, sardines and anchovies. In Australia the GoodFish app helps you choose sustainably.

- Be adventurous with the species you eat. Humans eat only about 1% of the species of fish, crustaceans, bivalves, seaweeds, etc. that live in our seas, rivers and lakes. In Australia, salmon, tuna and prawns account for about 20% of our seafood consumption. But it’s good for the environment and good for you to eat a diversity of sustainable species. Try something different next time you eat seafood.

- Be adventurous with the parts you eat. About 15% of the seafood produced each year is wasted. Some cultures, for instance the Japanese, are much more enthusiastic about eating the whole fish than others, for instance the Brits. But you can do something with every bit of the fish, although some of us may need a little help to understand the possibilities.

- Buy local, sustainably managed seafood. It’s fresher, tastier and more nutritious. It hasn’t travelled many fish miles. It’s less likely to have involved maltreatment of workers and plundering of small islands’ fish stocks by industrial trawlers from the other side of the world. Always ask where your purchases in restaurants and fish shops were caught or produced. Even if the staff don’t know, you’re making a point.

Disappearing mangroves

The world’s mangrove forests cover about 150,000 km2 (roughly two-thirds of Victoria). About 15% of the world’s coastlines, mainly in tropical, sub-tropical and warm temperate coastal areas, are covered by mangroves. Most of the Australian coast from the NSW-Victoria border, north around Queensland and the NT, and south almost to Perth has mangroves.

The loss of mangroves has serious social and economic implications for local communities and the world at large. They provide habitat for many species, support local communities with food and employment, protect coastlines and coastal properties from flooding, and store massive amounts of carbon for long periods. Unfortunately, mangrove forests have a history of destruction for agriculture and shrimp farming, and from the construction of dams on rivers changing freshwater and sediment movements. Mangroves may have their feet in salty water but they also need intermittent fresh water. More recently, they are also challenged by sea level rise, ocean warming and increased frequency and severity of storms, all caused by climate change.

More than half of global mangrove ecosystems are at risk of collapse, with nearly 10% Critically Endangered or Endangered. Without additional protection, by 2050 a further 7,000 km2 (5%) will be lost and 23,000 km2 (16%) submerged. An ecological assessment of 39 mangrove systems globally included four in Australia: the Coral Sea, NW Australia, SW Australia and E & SE Australia. The first three were categorised as Least Concern but the mangroves in E & SE Australia were categorised as Endangered.

The Global Mangrove Alliance of NGOs, governments, scientists, industry and local communities aims to halt the loss of mangroves, restore half of those lost since 1996 by 2030, and ensure 80% of remaining mangroves are in long-term protected areas.

Cemeteries are for the living

This hamster is supplementing his diet in his local graveyard. The headstones, graves, stone walls, shrubs, hedges and trees in cemeteries provide a wide range of benefits for local wildlife.

East London’s Tower Hamlets Cemetery provides a home for over 1,100 species, including over 450 species of beetle, while north London’s Highgate Cemetery gets high marks as a refuge for a rare orb-weaving cave spider. Graveyards can also provide stepping stones for migratory species, a home for solar panels and a cooling environment for the living by reducing the urban heat island effect.

Unfortunately, climate change, particularly storms, flooding and sea level rise, is damaging burial sites. Locally, ancestral burial grounds on low lying Pacific and Torres Strait Islands are already being disturbed.

Sexually deceptive orchids

Australia is the main home of greenhood orchids, of which there are about 300 species globally. Greenhoods produce chemicals that resemble the sex pheromones of female fungus gnats. Male fungus gnats, doing what comes naturally, try to mate with the orchid but as they go deeper into the flower a door closes behind them (watch the video in this article). The only remaining way out forces them past the orchid’s sexual organs and they inadvertently collect or drop off some pollen. On the gnat goes to another flower and … well, you know the story from here.

Gnat and orchid are choosy though and sometimes the love chemistry just isn’t right (watch the Pt jonesii video).