Environment: NSW’s environmental assessment process for logging ignores the previous 200 years

August 18, 2024

Ignoring 200 years of native forest logging underestimates the consequences of current logging. Beware of false solutions for plastic pollution. How to make your garden bird-friendly.

It’s not just this year’s native forest logging that matters, it’s the previous 200

Australia has a dreadful environmental record, e.g., one of the world’s highest per capita emitters of greenhouse gases; a major exporter of fossil fuels; high levels of mammal extinctions in the last 200 years; enormous areas of land cleared since colonisation; the only developed nation identified as a current deforestation hotspot thanks to NSW, Queensland and Tasmania.

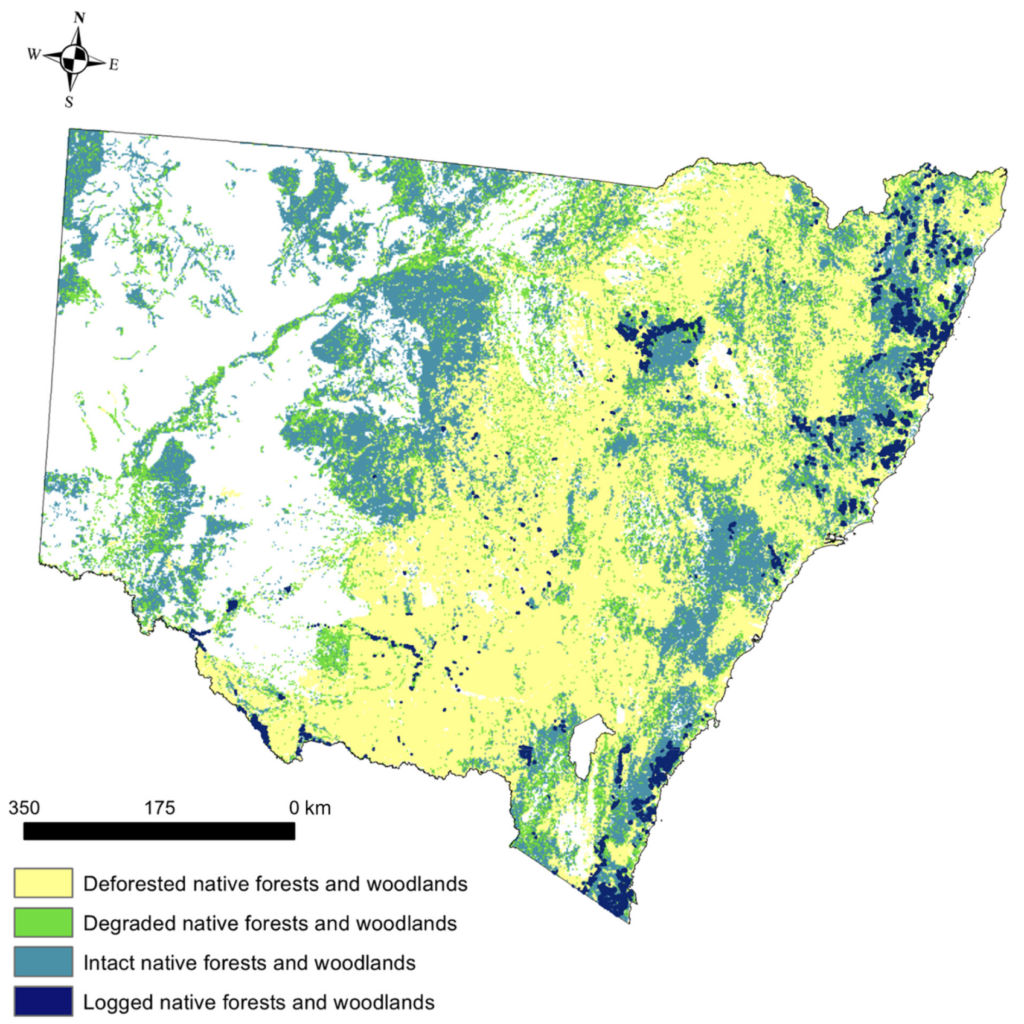

David Lindenmayer and colleagues have shown that over half (29 million hectares, an area about the size of New Zealand) of pre-1788 native forest and woodland in NSW has been lost, with most of the loss occurring in the eastern half of the state. Of the remaining 25 million hectares, 9 million is degraded, leaving just 30% of the pre-colonisation forest and woodland intact.

The map below displays the histories of four areas of forest and woodland in NSW. Note the vast areas of yellow representing forests and woodlands that were cleared between 1788 and 2021 and the green areas that display currently degraded forests and woodlands. The dark blue areas show the 435,000 hectares that were logged in 2000-2022, and the remaining intact forests and woodland are coloured teal. The colour distinctions are clearer in the link.

Of the 269 animal and plant forest-dwelling species assessed by the researchers, all except eight have been impacted by historical deforestation. Recent logging has further affected 150 of them, all of which are listed as Vulnerable, Endangered (51) or Critically Endangered (13). Forty-three species now have 50% or less of their pre-1788 habitat remaining and nine species have 30% or less. Koalas, black cockatoos and quolls are among the most impacted.

The research has several important implications:

- Widespread deforestation now results from many small areas of logging. Environmental impact assessments of new logging proposals currently examine each proposal independently and often conclude that the consequences for the environment, including biodiversity, will be inconsequential. It’s also worth noting that 93% of clearing events are not even referred for environmental assessment and formal approval.

- The failure to place new logging activities in the historical context results in a perpetually ‘shifting (declining) baseline’ of what is considered normal and a gradual deterioration in environmental standards and goals.

- The serious impacts of forest degradation (e.g. gradual loss of forest biomass, changes to species composition, erosion of soil quality) are often overlooked. As are the impacts of the roads built to facilitate logging, e.g. introduction of invasive species of animals and plants, and the spread of pathogens.

- The combination of logging and degradation with climate change makes the remaining forest more vulnerable to more frequent, more severe, more widespread bushfires.

- Current forestry regulations in NSW do a poor job of limiting the harmful impacts of logging and this threatens the ability of Australia to meet some of its international agreements and of NSW to honour its policy commitments.

- Spatial mapping and comparison of species’ habitats and logged and degraded forests and woodlands can identify areas where management and conservation efforts are most needed and most effective.

It is essential that assessments examine the projected environmental damage of each and every logging proposal in the context of the cumulative harm caused by 200 years of deforestation and degradation. Every new logged area (no matter how small) adds to the 29 million hectares already lost and reduces the 16 million remaining.

Plastic by numbers

- Between 2000 and 2019, the annual production of plastics doubled from 230 to 460 million metric tons. At current rates, it will triple again by 2060.

- 99% of plastics are made from fossil fuels.

- Plastics generate about 1.8 billion tons of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions per year, almost 4% of the world total.

- The major stage of the plastic life cycle associated with GHG emissions is primary production – the energy consumed during drilling for oil and gas and producing the plastics, and methane leakage. This stage alone produces more than 1 billion metric tons of CO2.

- Disposal and waste management of plastic, mainly through incineration and open burning, also produces GHGs, as well as many health-damaging air pollutants.

- About 14 million tons of plastic enter the ocean every year. The microplastics that are eventually produced limit the ability of microplankton to absorb carbon and disrupt food chains.

- If we continue on our current path, plastics will contribute about 20% of the total GHG emissions budget for keeping warming under 1.5oC by 2040.

Approaches to reducing the harm done by plastics must focus on all parts of the life cycle: upstream - reduce or eliminate the use of unnecessary plastics and reduce the GHG emissions associated with production; midstream - design and promote products that can be reused and recycled; and downstream - prevent plastics being incinerated and entering the natural environment.

Four false solutions for plastic pollution

To continue with business as usual, the producers (petrochemical companies) and major users (big brand manufacturers and retailers) of plastic have been promoting, with great success, false solutions to the problem of plastic pollution – solutions that don’t work but convince the punters either that they themselves can make a major contribution to solving the problem and/or that the producers and users are successfully tackling the problem. A report from Kenya identifies four examples of popular approaches to plastic pollution that make people feel good but don’t tackle the scale of the global problem.

- Recycling. Only 9% of plastics are recycled globally. The rest is burnt, buried or ends up in the environment. Even the countries that are doing recycling ‘well’, recycle less than 50%. Whether it’s mechanical or chemical, the recycling of plastic waste fails because it is extremely difficult to collect, virtually impossible to sort, environmentally harmful to reprocess, and uneconomical.

- Clean-up initiatives. Clean-ups have many local benefits (cleaner beaches and rivers, increased community pride, education, for example) but they tackle the symptoms without identifying and managing the cause. And because the symptoms keep appearing, the clean-ups are never ending – ‘akin to mopping the floor while the tap is still running’.

- Bioplastics are defined as plastics that are made from renewable organic material such as plants and/or are biodegradable. They seem to hold promise but producing plastic from plants currently runs the risk of interfering with essential food production, particularly in poorer communities. In addition, breaking them down often requires very specific conditions which are not widely available. Probable end result: plastics produced from a different source but still polluting the environment.

- Plastic-eating bacteria. In carefully controlled laboratory conditions these also look promising but success at scale in the natural environment is another story. Not to mention the risks of introducing genetically modified organisms into ecosystems. Again though, it’s treating the symptoms, not the cause.

The report’s recommendation is: ‘__What people and the planet urgently need is a Global Plastics Treaty that tackles plastic pollution at its source by drastically reducing production and massively enabling reuse and refill systems’.

Birds in the burbs

It’s not easy to see mammals, reptiles or amphibians in urban areas but it is usually pretty easy to see and hear birds, even through your own windows – as evidenced by the upsurge in bird watching during the covid lockdowns.

Birds come and go as they please, of course, but occupants of homes and commercial premises and owners of ‘public’ land such as councils, hospitals, railways, foreshore authorities, defence organisations and religious bodies can encourage birds to live in or visit their properties.

Different species have different habitat requirements and it’s unlikely that whatever you do will entice a white bellied sea eagle to visit your backyard birdbath in Sunshine or Paddington. But you can make some small changes to increase the number and variety of birds (and other animals) that visit your garden and places of work and recreation.

The Heritage Foundation: ‘oil demand will never peak’

Rigzone is ‘the leading online resource for news, jobs and events for the oil and gas industry’. The Heritage Foundation’s mission is ‘to formulate and promote public policies based on the principles of free enterprise, limited government, individual freedom, traditional American values, and a strong national defence’, (read ‘defend our members’ power, privilege and wealth while making the rest of you think that we’re helping you’).

This is what they came up with when they got together:

‘In an exclusive interview, Diana Furchtgott-Roth - Director, Center for Energy, Climate, and Environment, and The Herbert and Joyce Morgan Fellow in Energy and Environmental Policy, at the Heritage Foundation - told Rigzone that oil demand will never peak.

“The world will continue to demand more and more oil as countries get richer and demand for energy rises,” Furchtgott-Roth said.

“Peak oil is a myth originating with King Hubbard in the 1970s. It’s been disproved,” the Heritage Foundation representative added.

“Oil demand keeps going up and recoverable oil resources rise too, as technology improves and we have horizontal drilling and fracking,” Furchtgott-Roth continued.’

Sounds like the world’s oil resources should be called Albert.

Magnificent (green) tree frog turns blue

The Magnificent tree frog lives in the northern Kimberley and adjacent NT. It can grow to about 12cm. Normally it’s green with white spots but a rare genetic mutation has produced a bright blue one on the Australian Wildlife Conservancy’s Charnley River-Artesian Range Wildlife Sanctuary on Wilinggin Country.