Environment: Oil and gas producers underreport methane emissions

April 14, 2024

How accurately are methane emissions reported and whose estimates can you believe? Who should be the last producers of oil and gas? What are Australia’s commonest birds?

How well do you know our Aussie birds?

1 Which of the following are among Australia’s commonest ten birds:

- Rainbow Lorikeet

- Red Wattlebird

- Sulphur-crested Cockatoo

- Australian White Ibis

- Silver Gull

2 Name one of the three commonest bird species in your state or territory.

Drilling into oil and gas (3)

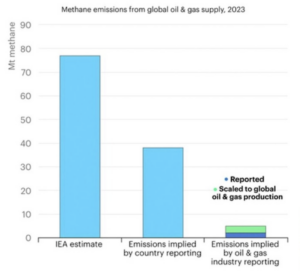

The histogram below displays three different estimates of the global methane emissions (in million tonnes, Mt) from the production and use of oil and gas in 2023. The IEA’s estimate is 77 Mt. The estimate produced by the UNFCCC, based on nations’ reporting of their emissions, is 38 Mt.

But the estimate of methane emissions produced by the industry themselves (the right-hand column in the histogram) is only 5 Mt, although this needs a little explanation. The Oil and Gas Methane Partnership (OGMP 2.0) covers about a third of oil and gas producers and their estimate of their own methane emissions in 2023 is the lower, dark blue part of the column (2 Mt). This estimate has been extrapolated to cover the other two-thirds of producers (3 Mt), the green part on top – hence the total of 5 Mt. Accepting for just one moment that the OGMP reporting is accurate, it’s possible that the OGMP members are better at reducing their methane emissions than the non-members and that the green part of the column should be even larger.

Possible reasons for the large discrepancy between the OGMP and IEA estimates are that the industry is failing to report fugitive emissions from accidental methane leaks (which are known to be huge in some cases), flaring of gas, and the burning of gas by companies themselves to power their own activities.

Fundamentally, the companies either have little idea of where their emissions are coming from and how big they are (wilful incompetence) or they know very well and dissemble (dishonesty). Either way, it’s not a good idea to let the oil and gas industry (any industry for that matter) self-monitor unless the results are independently audited and made public.

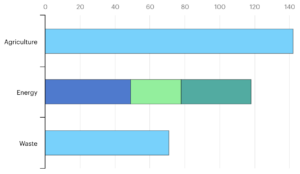

Just for the record, the IEA estimates that all fossil fuels produced almost 120 Mt of methane emissions during 2023.

That all said, wetlands naturally produce almost 200 Mt of methane emissions each year, a topic I touched on a couple of weeks ago.

North Sea oil and gas fuelling climate change

Starting in the 1960s, five countries have been extracting oil and gas from the North Sea. Norway and the UK have been and remain the main producers (93% of the current total between them), with Denmark, Germany and Netherlands a fair way behind. Combine the current outputs of the five and they become the seventh largest producer globally, although in fairness their total is only about a tenth of USA, Russia and Saudi Arabia combined.

Denmark, Germany, Netherlands, Norway and the UK are all rich countries that have a historically-based moral obligation and can afford to reduce their oil and gas production levels rapidly in line with keeping global warming below 1.5oC. Plus, they all like to portray themselves as paragons of virtue on climate action.

Unfortunately, all five countries have continued to approve new oil and gas extraction projects since signing the 2015 Paris Agreement. Norway and the UK, in particular, are making little effort to achieve the 80% reduction in production by the early 2030s that is required when principles of justice, equity and caution are applied.

This is not surprising as none of the five has a suite of policies that is aligned with meeting their commitment to the Paris Agreement. Nor is any of them contributing their fair share to the transition away from fossil fuels.

We all know, and more importantly they all know, what is needed: stop approving new developments; establish and implement a Paris-aligned date to end all oil and gas production; and adopt just transition policies. Don’t hold your breath.

As a personal aside, I well remember the gasman coming to convert our cooker to the heavily promoted ‘natural’ gas from the North Sea in the late 1960s. This was accompanied by the closure of the very smelly gasworks, situated almost in the town centre, that produced ‘town’ or ‘coal’ gas and stored it in its towering gasholder. The gasworks, which also produced coke, operated from 1836 to 1968. I imagine a similar transition occurred at some point in Australia.

In the UK, the transition to North Sea gas (methane) resulted in the disappearance of suicide by ‘sticking one’s head in the oven’. I am not being frivolous here. Because every house had a gas oven, and coal gas contained the highly lethal carbon monoxide, this was a readily accessible, relatively quick and common method of suicide in the 60s, providing you’d made sure to put a shilling in the meter beforehand, that is.

In a further sign of changing times, I also remember that there was no physical or legal obstruction whatsoever to members of the public, including schoolboys, walking right through the middle of the gasworks – it was a public right of way – and watching the whole fiery process. Should anyone be interested, there’s somewhat blurry 20-minute video about the 130 year history and operation of my hometown’s gasworks.

OH&S standards were generally much slacker back then. There was also no objection in the 1950s to a little boy wandering through the abattoir that was behind our house and watching the cattle, sheep and pigs being slaughtered – but that’s another story.

Who should be the last oil and gas producer?

That depends on what criterion one uses.

The place of origin of the oil or gas doesn’t make any difference to the emissions produced when the fuel is burnt. However, the emissions generated during the extraction and production processes (fewer than when the fuel is burnt but still significant) do vary greatly from place to place. Norway makes strong claims to be the last producer as its extraction is unquestionably the cleanest for both oil and gas at 36 and 26 kg CO2e per barrel of oil equivalent respectively. Many nations’ emissions are 2-4-fold higher and a few are 6-10 times higher.

Maybe price, mainly determined by production costs, should be the main consideration. Saudi Arabia (which also has relatively low emissions) scores well here as its oil and gas is close to the surface and cheaper to pump. Other Middle Eastern countries are not far behind. But Canada and China (oil), and Australia and Argentina (gas) are the most expensive producers.

Fairness in terms of a country’s historical greenhouse gas emissions and economic and social capacity to pay for and manage the transition away from oil and gas production are appealing to me. Fairness suggests that the historically high emitters of North America, Western Europe and Australia should be among the first to stop producing, whereas those countries with least capacity to pay for the transition (and hence can make a case to be the last ones standing) are Libya, Iraq and South Sudan for oil and Algeria, Trinidad and Tobago and Turkmenistan for gas.

This may seem like a nice little mind-game but the choice facing the governments of the world (who, let us not forget, have made a vague commitment to phase out fossil fuel use) is whether to engage with these issues and manage the transition in a somewhat orderly manner or let corporate power and market forces create chaos and much unnecessary suffering.

What happens to the oil and gas that isn’t burnt?

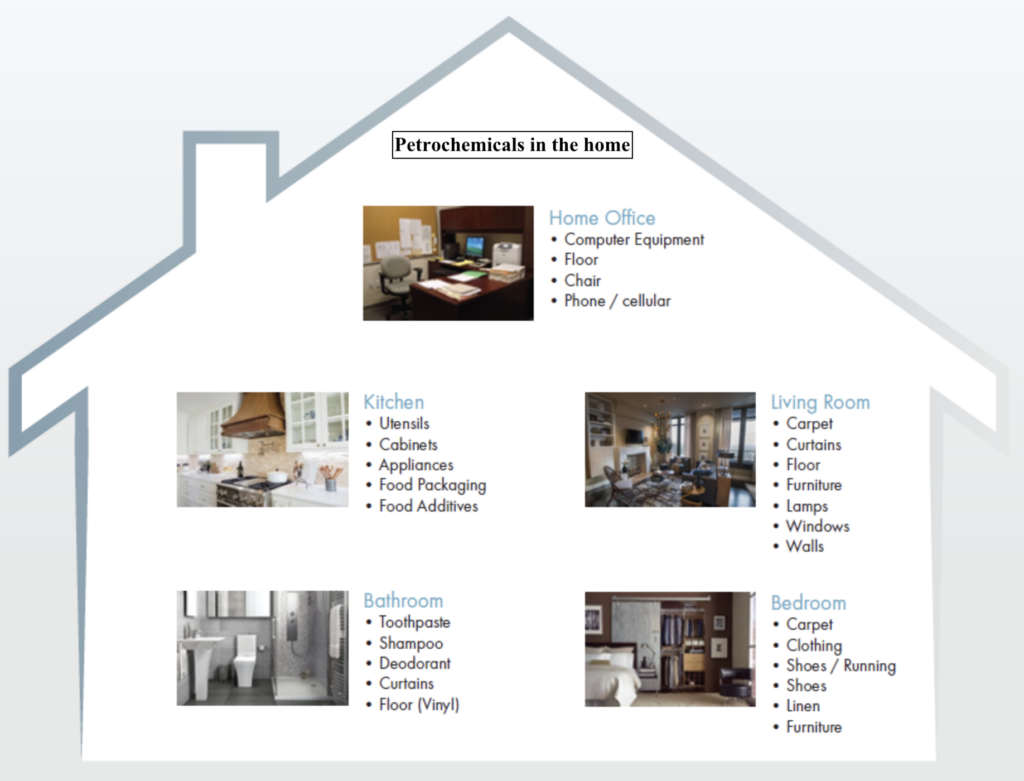

Part of the problem we have with oil and gas is that not all of it is burnt to produce energy, greenhouse gases and toxic waste. Lots of it goes into the petrochemical industry to produce a wide array of products on which we currently depend daily both industrially and domestically (e.g., Plexiglas, Teflon, Gore-Tex, Kevlar, Nylon).

The challenge is to eliminate as many of these products as we can and/or find alternatives that are less damaging to the environment and human health.

Australia’s commonest birds

For one week every October since 2014, birdwatchers around Australia have been recording for Birdlife Australia the species and number of birds they see during 20-minute observation periods. Each observer can submit as many 20-minute counts as they wish. Last October over 60,000 Australians counted over 3.6 million birds belonging to 597 species in the Aussie Bird Count.

The four most reported birds nationally (Rainbow Lorikeet, Noisy Miner, Australian Magpie and Sulphur-crested Cockatoo) have occupied the top spots every year. These four are undoubtedly common and they are also easy to recognise, except perhaps for the Noisy Miner (a native honeyeater) which many people confuse with the invasive Common (or Indian) Myna. The only newcomer to make it into the top ten over the decade is the much-maligned Australian White (previously known as Sacred) Ibis.

There is always some variation in the most recorded birds across the states and territories. Most out on a limb in 2023 was the NT where none of the top three birds featured in the national top ten. Disappointingly, in Tasmania two of the top three were introduced species.

Outside the top ten, there has been a decline in the reporting of smaller, specialist bush birds such as Silvereyes and fairy-wrens - victims of loss of habitat and cats, I suspect.

If you’d like to participate this year, put October 14-20th in your diary now and head to the Aussie Bird Count website.

‘Reckless’ covered for climate change

Angie McMahon covered Australian Crawl’s ‘Reckless’ (released in 1983 and familiar to many of P&I’s demographic, I imagine) on Triple J’s Like A Version recently. She also explained why she updated this particular lyric for the era of climate change and war crimes.