Environment: On track for 2 degrees of warming within 20 years

October 14, 2023

Based on whats actually happening rather than unfulfilled promises, the world will exceed 2oC of warming in the early 2040s and it doesnt look like a comfortable place to be (not even for succulents).

ExxonMobils world in 2050

ExxonMobils projections for the 2050-world, likely to contain 2 billion more people than today, are rather dispiriting:

- The economy will be more than double;

- Electricity use will have grown by 80%;

- Oil and natural gas will supply more than 50% of the worlds energy;

- Natural gas use will have increased by 20%;

- Solar and wind will supply 11% of the worlds energy;

- Energy-related CO2 emissions will have fallen by 25% to a mere 25 billion metric tons per year.

According to ExxonMobil, three scalable technologies hold the keys to this golden future: carbon capture and storage, hydrogen fuel and biofuels. And three drivers involving governments, companies, universities, everyone, will accelerate the energy transition:

- Public policy support: more money and fewer regulations for the private sector;

- Technology advances: with governments avoiding picking winners and losers;

- Market-driven solutions: markets everywhere.

Its easy for me to mock but the really scary part of all this is that ExxonMobils projections may be closer to the mark of what 2050 will look like than many others. They are based on an analysis of what is actually happening (and not happening) now, not what needs to happen to get to net zero and stabilise global warming. If ExxonMobil is right, we will be well and truly stuffed by 2050.

Of course, ExxonMobil isnt simply an objective observer here or a messenger pleading not to be shot. It has a big stake in and is a major influence on both the destination and the journey and, as the following quotation shows, it is keen to use the report to present some self-serving but questionable assertions as authoritative, compelling facts:

Energy use and improved living standards go hand in hand. You cant have one without the other. Fossil fuels remain the most effective way to produce the massive amounts of energy needed to create and support manufacturing, commercial transportation, and industrial sectors that drive modern economies.

Its possible that the second sentence is no more true of energy use and living standards than Frank Sinatra mistakenly suggested it was of love and marriage.

Climate Trackers world of today

In many ways confirming ExxonMobils gloomy 2050 outlook, Climate Tracker recently reported that:

- None of the worlds largest producers has committed to ending investments in oil and gas production. In fact, they are increasing them.

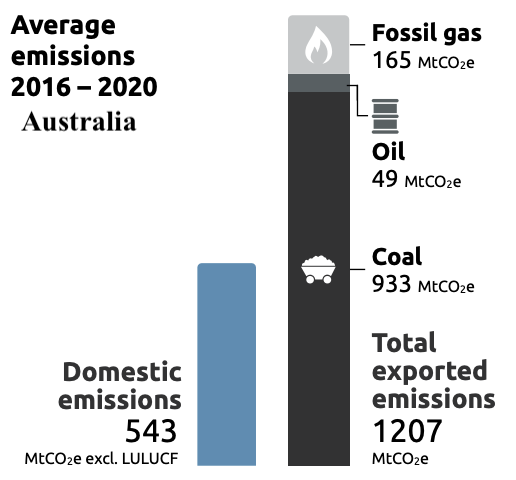

- Major fossil fuel producing countries such as USA, Canada, Norway and Australia are planning to expand their production and export of fossil fuels rather than fulfill their responsibility to lead the way and phase them out.

- Most governments have failed to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies despite their promises.

- G7 countries continue to support public finance for natural gas projects overseas despite their pledges to end new financial support in 2022.

- Major oil and gas companies have dumped their plans to reduce investments in production and are now increasing it. They also promoting technologies such as carbon capture and storage that prolong oil and gas production.

- Greenhouse gas emissions are still increasing.

- Current policies put the world on track for 2.7oC of warming by 2100.

Climate Tracker rated Australia as heading in the Wrong Direction regarding new permits for oil and gas production, setting a date for ending oil and gas production, ending fossil fuel subsidies, and promoting carbon capture and storage. The only domain in which Australia was considered to be taking Positive Action was creating favourable conditions for renewable energy.

So, what will a 2oC warmer world feel like?

NASA has released a high-resolution (25x25km squares) database of daily climate conditions over Earths entire land surface for the period 1950 to 2100. This has permitted prediction of when the global mean temperature will reach 2oC above the 1850-1900 pre-industrial level (the crossing year), and investigation of global and regional climate conditions (e.g., temperature, rainfall, relative humidity, wind speed) and their impacts (heat stress and fire weather) at the crossing year compared with the average for 1950-1979.

The results do not look good:

- Depending on the level of emissions in the near future, the crossing year will be somewhere between 2041 (high emissions) and 2044 (low emissions). Basically, weve done so little for so long that whatever we do with emissions over the next 20 years is going to make no real difference to when global warming exceeds 2 degrees.

Just to avoid any confusion, the crossing year doesnt refer to a single year exceeding 2 degrees of warming; its the higher bar of when the 30-year average exceeds 2 degrees.

- The crossing year refers to warming over land and sea. The mean warming over land where most of us spend most of our time - at the crossing year will be 2.3-2.8oC. In Greenland, Alaska and Northern Asia warming will be over 3oC.

Below, for simplicity I have summarised greatly the findings for the early 2040s over land compared with the 1950-1979 baseline:

- Rainfall will be higher globally by about 20mm/year but there will be considerable variation. There will be increases of 50-150mm/year in Canada, Greenland, Northern Europe, Northern Asia and tropical Africa, and a decrease of 100-150mm/year in tropical South America. Most of Australia will experience up to 50mm/year less rainfall annually.

- Globally, relative humidity will decrease by about 0.7% due to the higher warming over land than sea. Again though, there will be large regional variations with a decrease of 1.7% in the Amazon and a 3-4% increase in India being most concerning. Most of Australia will have slightly less relative humidity.

- Wind speed will continue its long-term slowing and will reduce by a further 0.04m/second. The biggest reductions (0.12m/second) will be experienced in North America and Northern Europe, while much of the southern hemisphere will have no change or slight increases. The largest increase (0.03 m/second) will be seen in the Amazon. All of Australia sees little change.

- Solar radiation will increase by about 15 Watts/square metre, with much higher increases in the Sahara, Middle East and central and north-west Australia.

- As a result of changes in temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, wind speed and radiation, almost the whole world will be more exposed to fire weather. Semi-arid areas will be most affected: all of Australia, USA, Southern Africa and Central Asia.

- Most areas of the world will be exposed to greater heat stress in terms of both a higher wet bulb temperature (2.5oC higher on average globally) and the number of days per year of extreme heat. Australia can expect to have a 1.5oC higher wet bulb temperature and about 10-15 more days per year of extreme heat.

By the time we reach the crossing year, the changed climate conditions and their impacts will be having obvious implications for human health, daily life, agricultural yields and the design of buildings, cities and transport systems. Changing temperatures, wind speeds, solar radiation and rainfall will also influence the generation of energy from solar, wind and hydro resources. Individual species of animals and plants and whole ecosystems will have varying degrees of success adapting to the altered climatic conditions.

Heat + Humidity = Danger

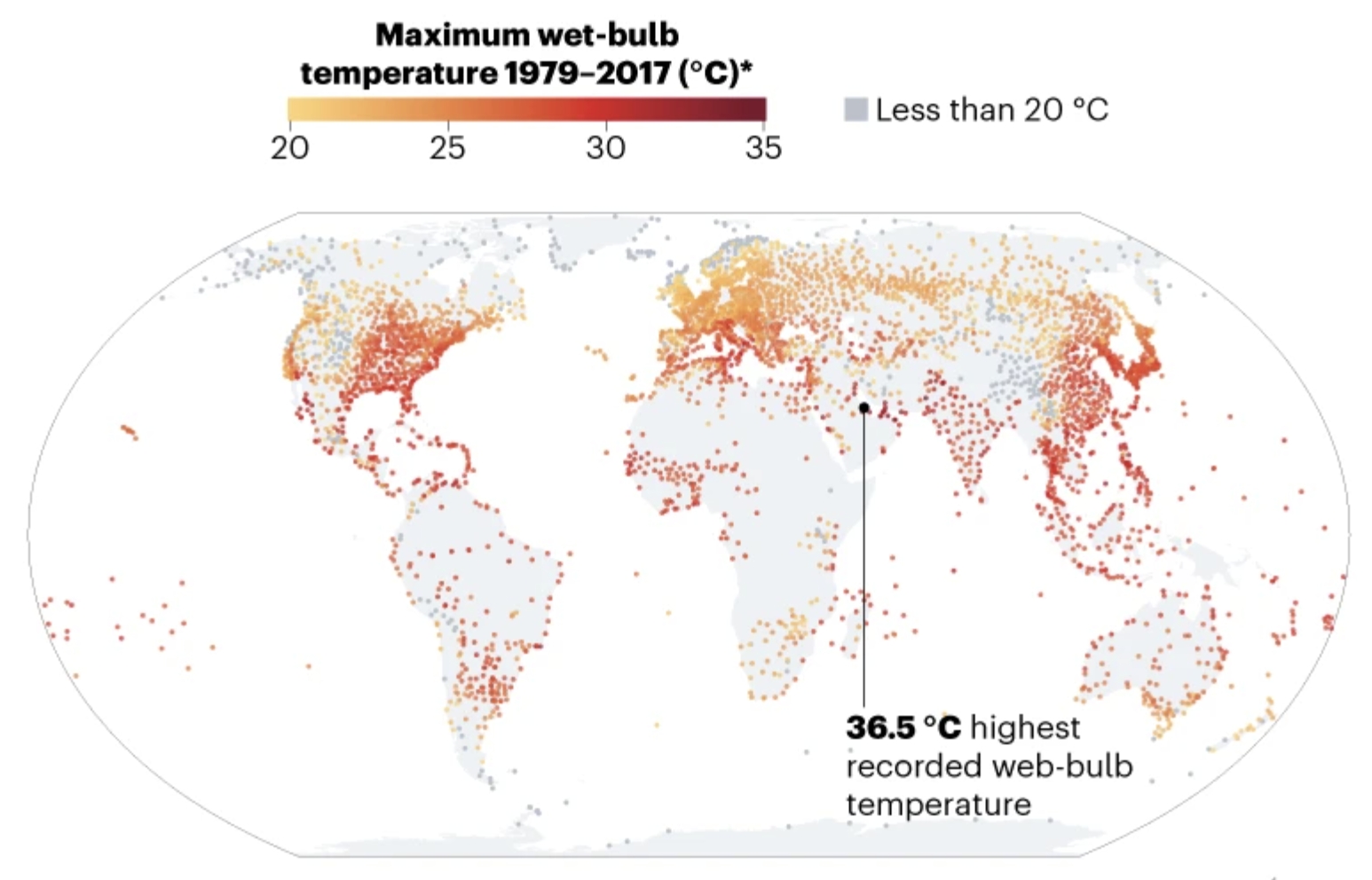

If you are struggling to get your head around the concept of wet bulb temperature, at what level it becomes dangerous for human health and survival, and what can be done to combat high wet bulb temperatures, an article in Nature provides more details, including research being conducted at the University of Sydney to explore how varying levels of temperature and humidity affect heart and kidney function. The map below displays maximum wet bulb temperatures in recent decades.

Based mainly on theory, it has been believed that, depending on the individual and the conditions, a wet bulb temperature of around 35oC is the limit of human tolerance. Recent empirical work has lowered this to around 31oC and suggested that as global warming exceeds 1.5oC and reaches 2oC increasing numbers of people will be exposed to dangerous hot and humid conditions in the Middle East, India, sub-Saharan Africa and China. The Americas and northern Australia will be increasingly affected when warming reaches 3oC.

Wet bulb temperatures have had particular significance for people in the northern hemisphere over their recent summer months where scorching dry bulb temperatures have felt a further 6-11oC higher when humidity has been high (the wet bulb temperature).

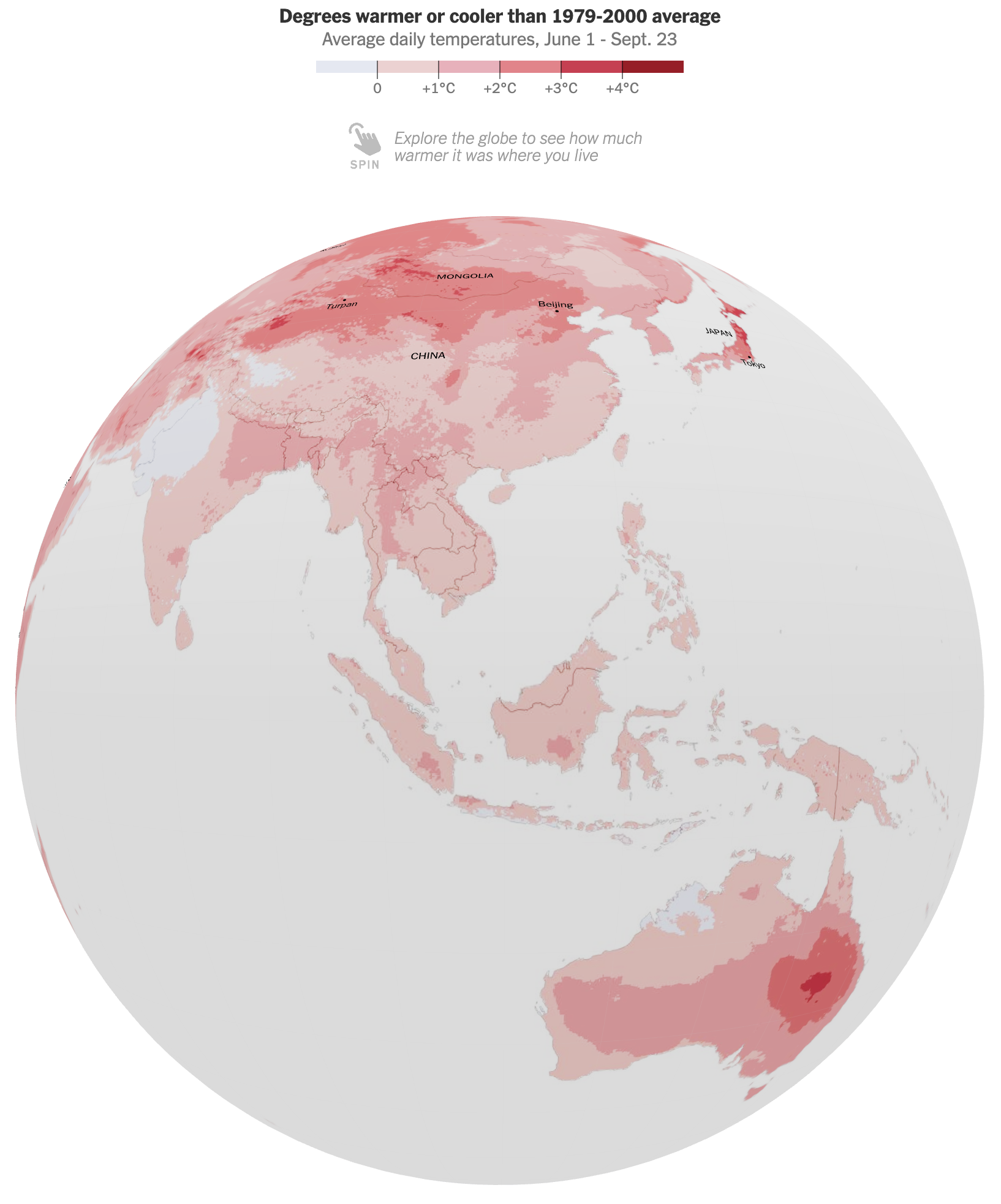

Even though its been winter, the average temperature in the southern hemisphere has been the highest on record. The temperature anomalies in the two hemispheres during June-September 2023 are clearly illustrated in the maps below.

Tallaganda Forest update

A month ago, I reported the plans of the Forestry Corporation of NSW to log the Tallaganda State Forest and the forty-day Stop Work Order issued by the NSW Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) in response to public outrage.

The size of the trees felled in the forest and the scale of the destruction is well illustrated in the photograph below (courtesy of Wilderness Australia).

In recent weeks, Wilderness Australia, WWF and South East Forest Rescue have been surveying greater gliders and their dens in the trees of the Tallaganda Forest and have submitted a report to the EPA. Im delighted to report that the EPA has extended the Stop Work Order for another forty days until November 13th. Watch this space.

Succulents: separate evolutions to similar outcomes

With half an hour to kill close to Sydneys Royal Botanic Garden, I wandered into the succulent garden, probably for the first time since Covid struck. We all know that succulents grow in arid areas but I hadnt realised that their distribution is very limited outside the Americas and Africa.

Nor was I aware that despite their very similar appearances the agaves of the Americas and the aloes of Africa (both are leafy succulents) have developed quite separately an example of parallel evolution. This is also true of stem succulents, the cacti of the Americas and the euphorbias of Africa.

It has traditionally been believed that Australia has very few succulents but this view has been challenged in recent years and there now seem to be over 400 Australian succulents.

Unfortunately, as with countless other plants, many species of succulents are threatened with extinction as a result of habitat loss for housing and agriculture, climate change, invasive species and even over-collection.