Environment: using the law to drive (and retard) climate action

August 25, 2024

Climate activists are increasingly using the courts to challenge development approvals and change the law, but so are action delayers. Access to electricity is increasing worldwide, but fossil fuels still dominate electricity production.

Climate litigation increasing worldwide

Lots of decisions on development proposals by environmental protection authorities, land and environment courts and ministers for the environment and planning are subjected to legal challenges by members of the public, non-government organisations, corporate entities, even Governments themselves if they are unhappy with the decision. This is sometimes referred to (pejoratively) as lawfare when the challenge is lodged by organisations concerned about the environment, but as far as I’m concerned it is perfectly right and proper to use the law and the courts in this way.

Less common but perhaps more important in the long term is strategic "climate change litigation" where a win is important for the specific case and also contributes to changing policy or the law related to climate change and/or influencing the public debate about climate action. These cases can be fought in sub-national, national or supranational jurisdictions, including international courts of human rights and justice.

Even a loss in strategic litigation, although disappointing for the plaintiffs, may still have an influence by, for instance, exposing a deficiency in policy or the law, clarifying the law or broadening the public debate. So, whatever the outcome in the court, strategic litigation might spur legislative reform, encourage financial regulators and insurance companies to become more active around climate risk, or even simply highlight issues with the public through the public hearings and reporting of the case.

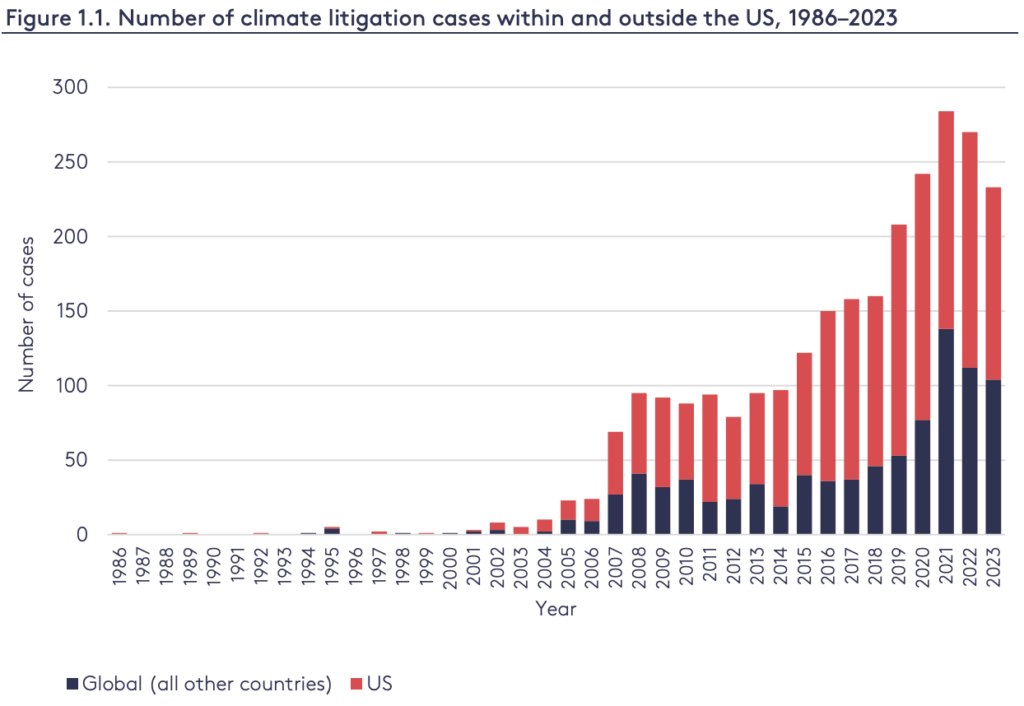

A global database of climate change litigation has identified 2,666 cases, 70% of which have been filed since 2015. The US, with 1,745 cases in total, is far and away the most popular jurisdiction, with the UK (139 cases), Australia (134), Brazil (82) and Germany (60) well behind but still having significant numbers. In total, 55 countries, including some in the Global South, have now had at least one case of climate change litigation. During 2023, 233 cases were initiated globally.

The cases heard to date often:

- Challenge the ambition or implementation of a government’s climate policies.

- Attempt to integrate climate considerations into decisions within a particular policy area, for instance the assessment of proposals for new fossil fuel production or electricity generation projects.

- Seek monetary damages for an alleged contribution to harm caused by climate change (‘polluter pays’).

- Seek to change company policies and governance to reduce their high emitting activities.

- Challenge a government or company for failing to reduce climate change-related risks in society or in their own business activities.

- Challenge inaccurate government or corporate narratives about their climate actions (‘climate-washing’). This has been a growing area in recent years with more than 70% of cases being decided in favour of the claimants.

- Attempt to reduce the flow of finance to activities that are not aligned with climate action.

As an example, the International Court of Justice will soon begin hearing evidence on two important questions:

- What are countries’ obligations under international law to protect the climate from greenhouse gas emissions? and

- What should be the legal consequences for countries when their actions or failures to act cause harm?

The database report anticipates three future trends in climate litigation:

- More legal disputes over recovery efforts following climate disasters, for instance challenging the reconstruction of fossil fuel infrastructure.

- Expansion of the concept of ecocide into national legislation.

- Incorporating climate change concerns into broader environmental issues (e.g., into plastic pollution and rights-based environmental cases).

The University of Melbourne maintains a database of Australian and Pacific climate change litigation.

Not only the angels use climate litigation

Not all the litigation tries to protect the environment or the cultures, livelihoods and health of current and future generations. Nearly 50 of the 233 new cases filed in 2023, again mostly in the US, many by companies or trade associations, were using legal tactics to obstruct climate action. These involved, for instance, allegations of deception and breach of fiduciary duties when climate risk was incorporated into financial decisions, and suits brought against environmental NGOs and shareholder activists for speaking out about climate change. This development is hardly surprising — what’s good for the goose is good for the gander — but bearing in mind the usually far greater resources available to corporate entities than individuals and NGOs, such cases can be more focused on intimidation than application of the law.

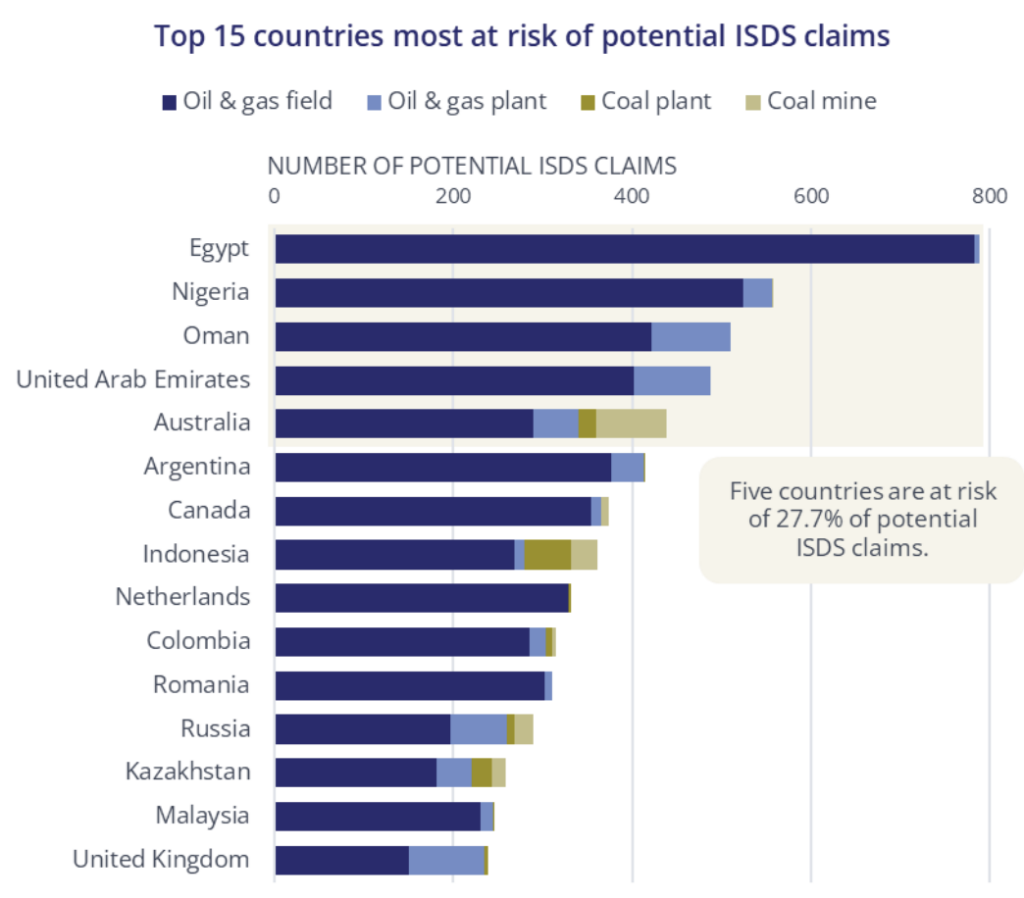

It is particularly concerning that some litigation opposing climate action occurs not within properly constituted, publicly accountable courts of law but in secretive tribunals established by international trade agreements to consider claims for compensation by companies that feel that their financial interests have been damaged by a country’s policies or legislation – a process known as Investor-State Dispute Settlement. Australia ranks fifth in the world for its exposure to potential ISDS claims by fossil fuel companies seeking billions of dollars in compensation for government climate change policies.

The most notorious local example is Clive Palmer’s various ISDS claims for hundreds of billions of dollars compensation from the Australian Government after his plans to build mines in WA and Queensland collapsed. Basically, the ISDS process is completely incompatible with the responsibility and ability of governments to take action to protect the health of its inhabitants and the environment.

Junk your Junipers

Junipers, true junipers that is, of which there are about 60 species, are evergreen shrubs and trees that are members of the cypress family. They are widespread across the northern hemisphere but not native to Australia. Many are now grown in gardens in Australia and the berry (actually a pinecone, not a berry) of one species is an essential ingredient of gin, of course.

Attractive they may be, but junipers are highly combustible, explosive even, due to their volatile oils, dense growth and retention of dead plant material. Householders in fire-prone areas in Boulder, Colorado are being encouraged to remove them. If you live in a fire-prone area (where isn’t fire-prone these days?) and you or your neighbours have junipers in the garden, maybe you should consider removing them.

Native juniper, a figwort shrub found along the coasts of the southern half of Australia, and Juniper-leaf grevillea are not true junipers.

The where and how of electricity generation

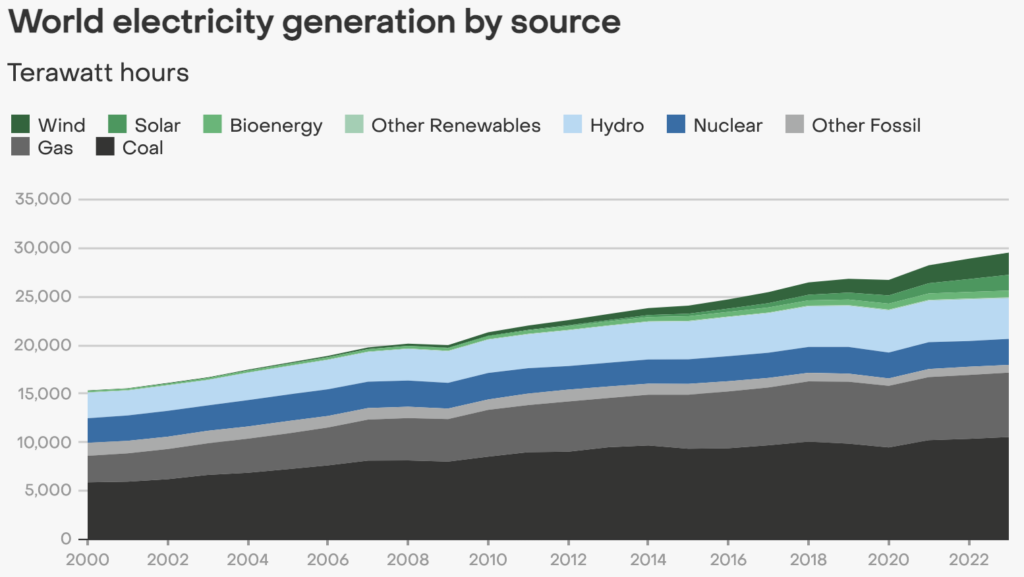

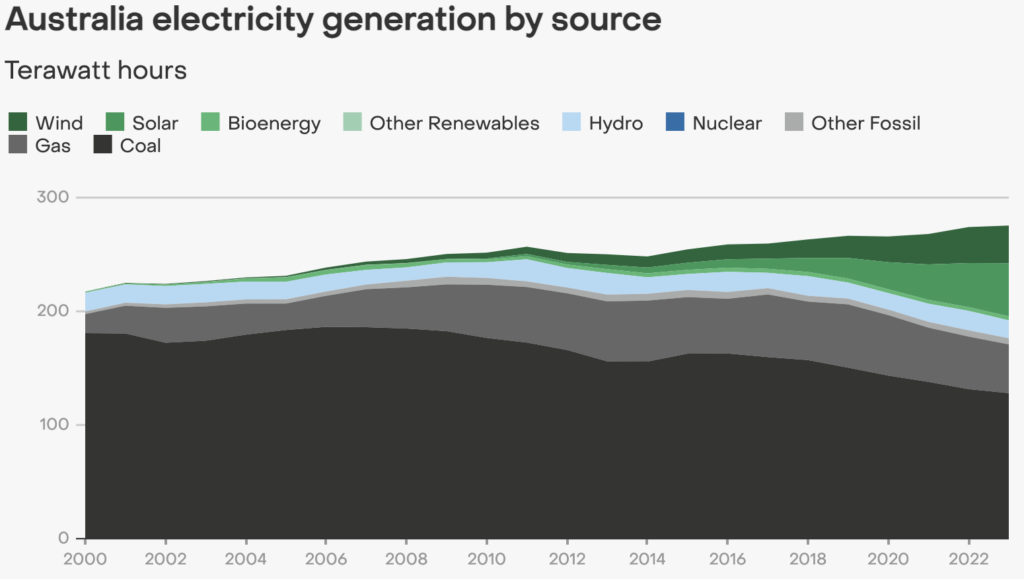

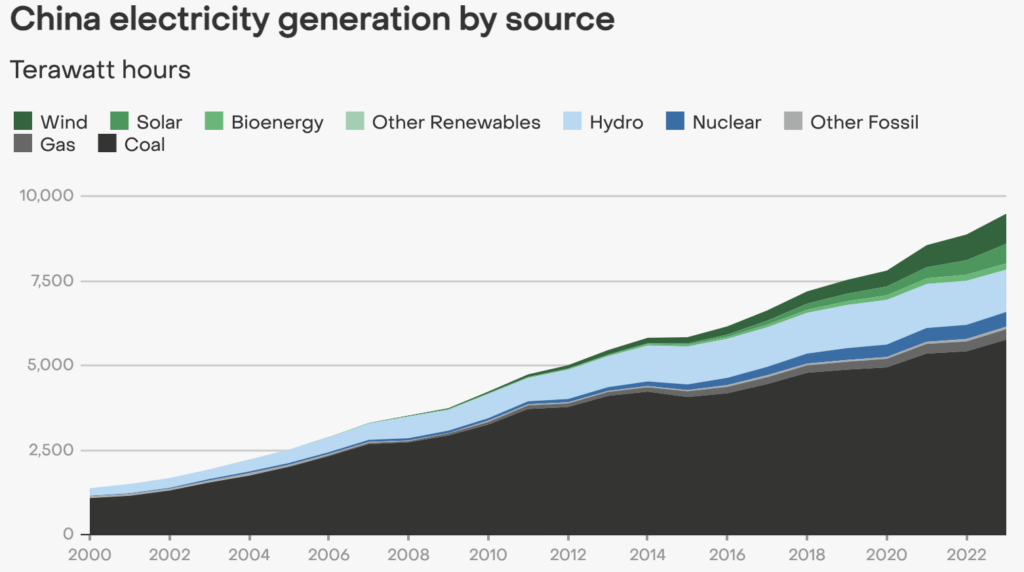

The three graphs below show the sources of electricity for the World, Australia and China between 2000 and 2023.

Obviously, the amount of electricity generated varies enormously, with Australia being two orders and one order of magnitude lower than the world and China respectively. China generates about a third of the global amount. Notwithstanding the very different amounts generated from different sources and the different trajectories of total electricity generation over the decades, in 2023 fossil fuels supplied a similar proportion of electricity in all three (around 65%).

If you follow the link above, you can explore similar data for the countries of your choice. If anyone cared to look at it, I suspect that there would be a fairly direct correlation between the amount of electricity generated in 2023 and the number of Olympic medals won at the recent games, although confounding rather than causation is the likely explanation.

But who gets to use all this electricity?

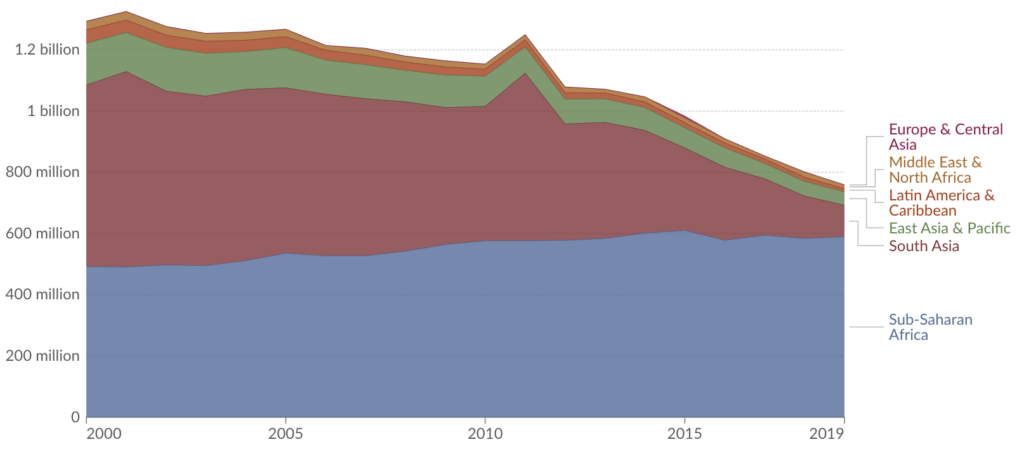

Between 2000 and 2019 the number of people worldwide with access to electricity capable of providing basic lighting and charging a phone or powering a radio for four hours a day increased from 4.8 billion to 6.9 billion. The number without access almost halved from 1.3 billion to 761 million. The gains were not attained equally across the world, however.

People in South Asia were the big winners, with the number lacking access to electricity falling impressively from 593 million to 103 million. Unfortunately, the number of people in Sub-Saharan Africa without access increased by 20% from 492 million to 589 million.

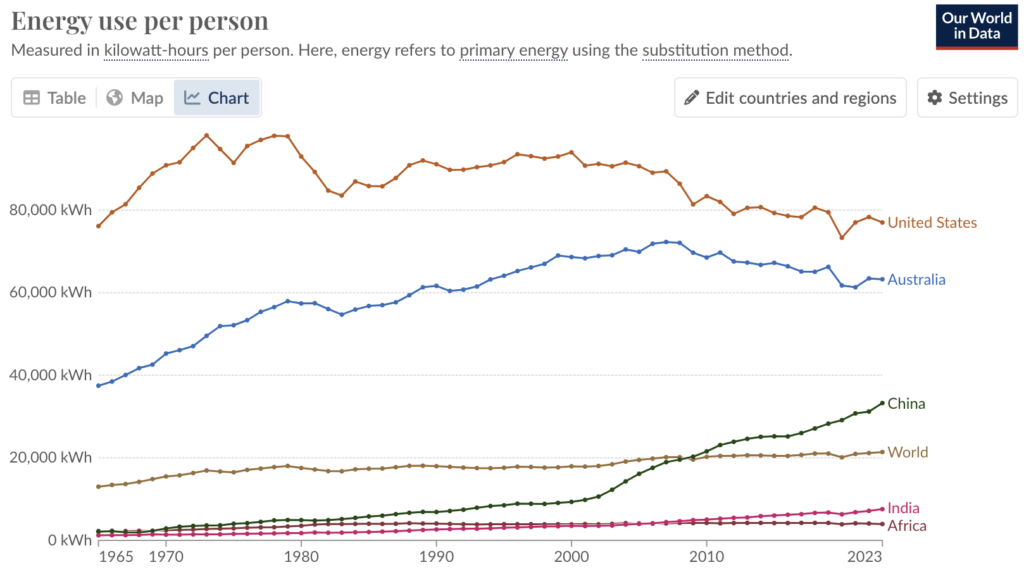

Not surprisingly, this is all reflected in the energy use per person in different countries and regions.

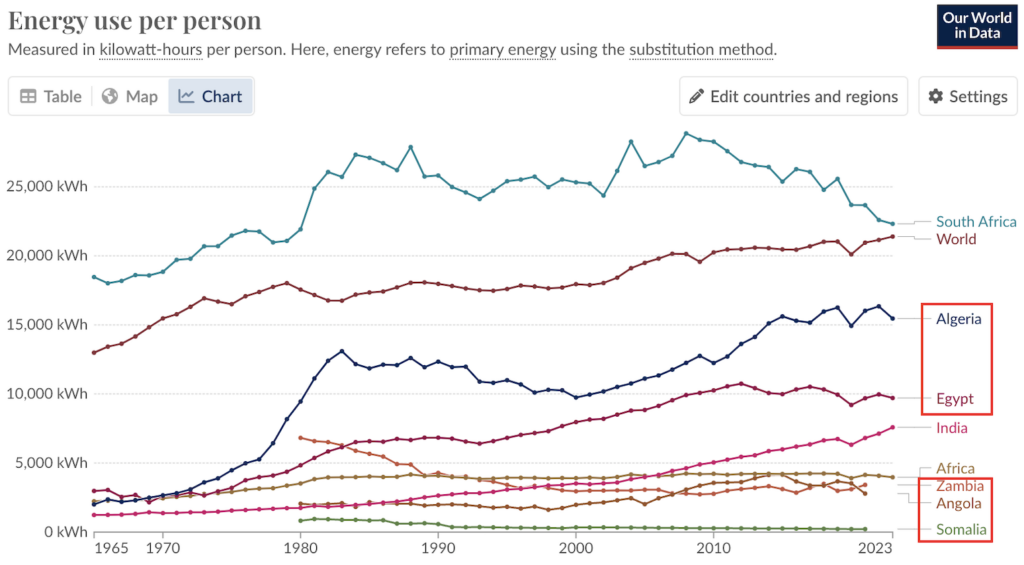

Note in particular the positions of the World and Africa in the graph above. Now see below the enormous differences within Africa. South Africa’s usage has been falling for almost 20 years and is now almost the same as the global average. North African countries are below the world average, but steadily increasing, roughly in parallel with but higher than India. But usage per person in Sub-Saharan African countries is well below the world average and not going anywhere.

Winter wattle

If you’ve got rid of your juniper bushes, you might consider replacing them with Sweet Wattle (Acacia suaveolens) which has attractive flowers in winter, thrives in full sun to partial shade near the coast and is named for its scent (suaveolens: sweet-smelling). Plant a few of them and your garden could look like the Sydney-Canberra road at present.