Environment: When will politicians take climate change seriously?

June 9, 2024

Both the WHO and UN may be starting to take seriously the effects of climate change on health. A global plan to save 1,000 freshwater fish from extinction. Covid reverses life expectancy at birth.

WHO resolution on climate change and health

It’s difficult to know whether to celebrate (the achievement) or groan (about the delay) but the World Health Assembly last week adopted its second resolution on climate change and health – the first was fifteen years ago. This follows hard on the heels of last year’s COP meeting in Dubai when the UNFCCC held its first ever health and climate day, convened a meeting of health ministers and developed a Declaration on Climate and Health.

It seems incredible that when the catastrophic consequences of climate change on people’s health have been so obvious and so well documented for more than a decade, the UN and the WHO have both been so slow to focus their attention on the issue. Maybe not so incredible though when one remembers that both organisations are run by (and for) the same people, the national governments of the world, many of who are not at all keen to discuss, let alone tackle, serious climate- or health-related issues.

The WHO resolution recognises that climate change is a major threat to both current and long-term health and wellbeing: ‘increasingly frequent extreme weather events and conditions are taking a rising toll on people’s well-being, livelihoods and physical and mental health [and] changes in weather and climate are threatening biodiversity and ecosystems, food security, nutrition, air quality and safe and sufficient access to water, and driving up food-, water-, and vector-borne diseases’. The resolution also notes that health systems themselves contribute to environmental pollution and release approximately 5% of global carbon emissions.

However, the most important statement in the resolution is that ‘any further delay in concerted global action on adaptation and mitigation will miss a brief and rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all’.

Having rehearsed the seriousness and urgency of the situation, what does the WHO resolution (which is non-binding on the member states) propose? First, it asks the member states to pull their collective finger out: conduct more health assessments and monitoring, develop plans to lower health services’ greenhouse gas emissions (‘only when doing so does not compromise health care provision and quality’), promote collaboration across government departments, invest in climate adaptation, raise awareness in the general public, and promote research and development. All motherhood statements – still, it’s a start.

Second, it requests the Director-General to develop for the WHO a plan of action on climate change and health and a Roadmap to Net Zero by 2030 (it isn’t clear to me whether the roadmap needs to be developed by 2030 or net zero needs to be reached by then), and to accelerate the implementation of WHO’s actions on climate change and health.

Lacking from the resolution is any mention of the role of fossil fuels in causing the severe threats to public health and the need for a just transition to renewable energy as soon as possible.

Taken together the WHO’s resolution and the UN’s Declaration do place the health consequences of climate change on the agendas of the world’s foremost intergovernmental organisations and provide a lever that can be used to promote stronger action on both mitigation and adaptation at national and subnational levels. The best thing going for the resolution and the Declaration is that the heads of the two organisations, particularly António Guterres at the UN, have already demonstrated strong leadership on these issues.

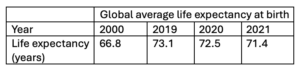

Covid has reduced life expectancy

While the origins of Covid remain unclear – spill over from nature or escape from a high security lab? – the consequences are much more obvious. The WHO has reported that global average life expectancy at birth (how long, on average, a baby born in any particular year can expect to live if current death rates continue to apply) declined by 1.7 years during the first two years of the Covid pandemic. This followed many decades of increasing life expectancy at birth. The table below shows the data since 2000. The 2021 figure of 71.4 years is the same as it was in 2012 - Covid has eliminated almost a decade of improvement.

The Americas and Southeast Asia were the regions that suffered the biggest decline (3 years), while the Western Pacific fared best (losing only 0.1 years) during Covid’s first two years. Throughout the period shown in the table, women have enjoyed a life expectancy at birth about five years longer than men.

Figures just released by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare demonstrate that Australia was not immune from this phenomenon. After 60 years of continuously increasing, the life expectancy at birth of both women and men fell by 0.1 years during the first three years of Covid (2020-22) compared with the 2019-21 triennium.

Saving Galaxia

Maybe it’s just me but I have the impression that, with the exception of plastic pollution, the oceans receive much less conservation attention than the land but that freshwater fish receive even less attention than marine fish. So, I’m delighted that there’s an initiative to stimulate more protection of the world’s freshwater fish.

Rivers, lakes and wetlands cover less than 1% of Earth’s surface but are home to 12% of all known species, including 18,000 species of freshwater fish. This is half of all known fish species and 200 new freshwater fish are described every year. Unfortunately, there has been an 84% decline in freshwater population sizes since 1970, the extinction rate in freshwater ecosystems is four to six times higher than in marine and terrestrial environments, and a quarter of freshwater fish species are threatened with extinction.

The SHOAL initiative is a partnership, established in 2019, that aims to engage with and build the capacity of a wide range of organisations to escalate conservation action to halt extinctions and save 1,000 of Earth’s most threatened freshwater fish species by 2035. SHOAL’s approach is to support local organisations around the world to implement interventions that focus on the conservation of specific fish species and sites. However, by conserving freshwater fish, SHOAL will also be protecting thousands of other freshwater species and their ecosystems.

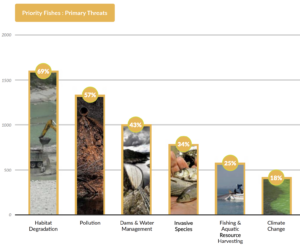

SHOAL has assessed the conservation status of almost 15,000 fish and prioritised over 2,300 that need urgent protection. Most of these are restricted to very small areas and it’s the usual culprits that are changing the conditions in which they have evolved and thrive. The figure below shows the percentage of priority fish threatened by each factor.

Only 12% of the priority fish are receiving any direct conservation action and even that is mostly very limited. Local action is essential but suitable local partners are rare and usually under resourced. The good news, however, is that many species do not require vast resources. The SHOAL Blueprint for action outlines strategies to target the most threatened fish, assist local stakeholders’ and conservation agencies’ programs, and build a global movement based on the best science.

Three-quarters of the priority fish are found in just 20 countries. Brazil tops the list with 263 and Australia comes 8th with 80 species. Most worryingly, Australia has five of the most threatened 25 species in the list of Evolutionary Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) freshwater fish, including two at the very top. Number one is Lepidogalaxias salamandroides or salamanderfish found in the southwest tip of WA and number three is Milyeringa Justitia, a 2cm long cave dweller with no eyes found on Barrow Island, WA.

An intergenerational crime against humanity

Returning to the seriousness and urgency of the climate crisis, I thoroughly recommend Joëlle Gergis’s recent article in The Conversation – an extract from her longer essay in the June 2024 edition of The Quarterly, ‘Highway to Hell: Climate Change and Australia’s Future’.

Stressing the urgency of action, Gergis recommends: ‘Forget the critical decade, what happens every single month during the next handful of years is crucial in determining how quickly we drain the remaining carbon budget needed to achieve the temperature goals of the Paris Agreement.’ She then relates how ‘People who have been working in the [climate science] field for decades are no longer sugarcoating the bad news – they want us to feel an appropriate level of alarm and outrage. We need you to stare into the abyss with us and not turn away.’

As someone who has been harping on about the urgency for well over a decade, I have never understood why some of the climate scientists I most respect as scientists have been keen to avoid scaring the horses in their public utterances. The herd should have been galloping like crazy for a long time now. A gentle trot would have been fine if we’d got serious 30 years ago but it’s too late for slow-and-steady now.

The subtitle of Dr Gergis’s article is ‘what will it take for political leaders to start taking climate change seriously?’. That is indeed the crucial question. Until that happens, and as I keep saying I see no prospect of it happening in the foreseeable future, we will continue hurtling towards a 3-4oC hotter world. And that’s the global average remember. It will be hotter over the land and it will be hotter in some places than others.

Gergis concludes: ‘It makes me wonder if people in decades to come will look back at the world’s collective failure to shut down the fossil fuel industry in time and see it for what it really is: an intergenerational crime against humanity.’

Honey possum in the pink

A heart-warming photo to celebrate World Environment Day on June 5th. The theme was Restoration.