Environment: will humans behave like monkeys when climate apocalypse strikes?

July 14, 2024

Summers right across the northern hemisphere are getting hotter but vegetation can lower the temperature locally. Macaques show humans how to cope with hotter conditions. Poor progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals.

Northern summers are getting hotter

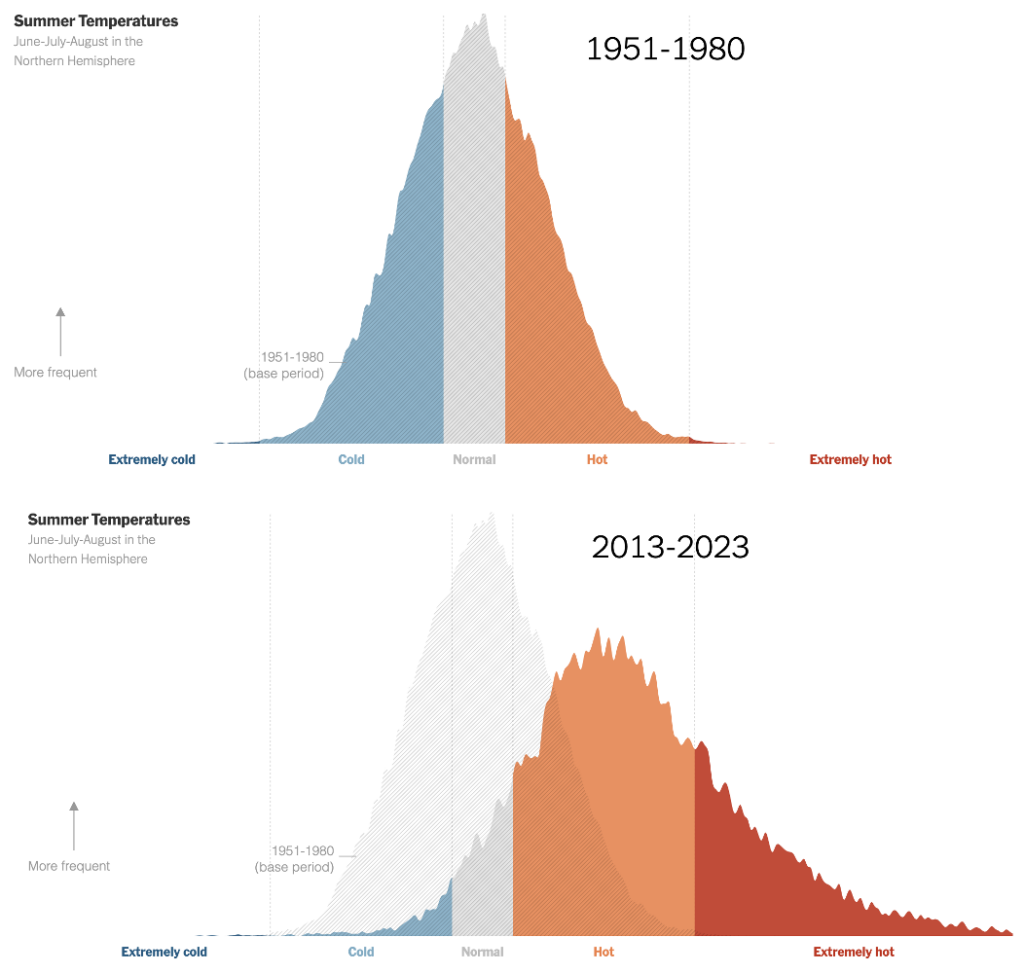

Sometimes a picture is worth a thousand words, even if not all the details are clear (the axes in the two graphs below).

But to add a little clarity, the graphs display land temperatures across the whole northern hemisphere in June, July and August during 1951-1980 and 2013-2023. Because the graphs cover such a wide range of locations – pole to equator, coast to hundreds of kilometres inland, sea level to high altitudes – the horizontal axis relates to whether the temperatures are ‘cold’, ‘normal’ or ‘hot’ for each specific location.

Not only is the mean temperature hotter in 2013-2023, but also the range has flattened and shifted well to the hotter right. In essence there is a new ‘normal’. Temperatures that were considered ‘cold’ and ‘normal’ occurred about two-thirds of the time in the earlier period but by the later period the same temperatures occurred only about one-eighth of the time. The frequency of temperatures that were considered to be ‘hot’ and ‘extremely hot’ have increased greatly, particularly for ‘extremely hot’ which has increased from less than 1% to over 25% of the time. (In the link, these two graphs are the end points of an animated display.)

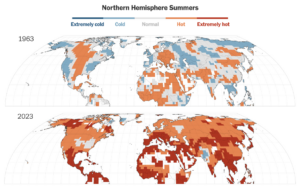

The next two maps show the temperatures over land in the northern hemisphere during June, July and August in 1963 and 2023. It’s glaringly obvious that almost everywhere north of the equator is now experiencing hotter summers, and it’s only going to get hotter.

Hot macaques display the Dunkirk Spirit

When the climate apocalypse arrives and it’s Hothouse Earth one day, storms and floods the next, food and water is scarce and infectious diseases are running amok, how are humans going to respond? Will we be at each other’s throats, hoard what we’ve got, steal toilet paper from our neighbours and invade previously friendly countries that have more trees? Or will we all muck in together, make the best of a dire situation, pool and share what little we have and help as many people as possible to survive? If Rhesus macaque monkeys are any guide, maybe our better selves will rise to the surface.

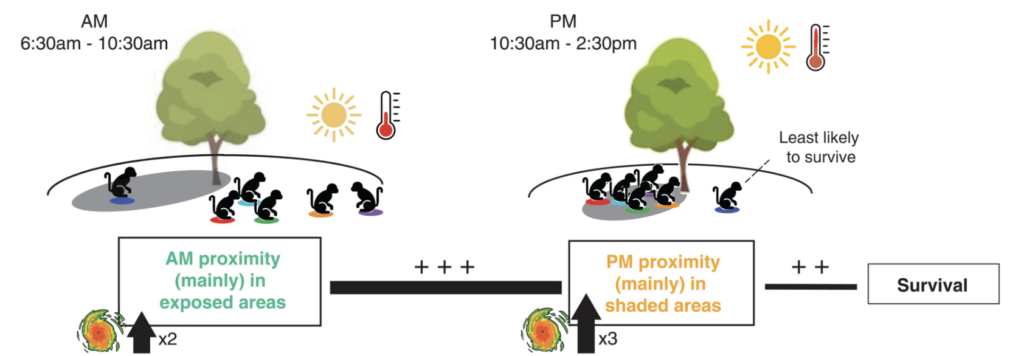

In 2017 Hurricane Maria caused devastating destruction to the vegetation of Cay Santiago, a small island off Puerto Rico. Two-thirds of the tree cover was lost and five years on it was still reduced by about 50%. Temperatures on the island regularly exceed 40oC. In the afternoons, there can be an 8oC difference between shaded and unshaded areas.

Macaques are widely regarded as one of the most hierarchical and cantankerous primate species, very intolerant of physical closeness to each other. Santiago was home to a colony of about 600 macaques when Maria struck. After the hurricane, food and shade became extremely scarce.

How would the normally testy macaques respond, with increased aggression to each other or greater cooperation? As it turned out, they got along together pretty well:

- In the year after the hurricane, the monkeys were less aggressive to each other and three times more likely to tolerate other monkeys nearby, thereby facilitating access to the scarce shade that is vital for their thermoregulation. Although their newfound tolerance fell away somewhat over the next four years it remained much higher than before the hurricane.

- The number of colony members that each monkey would tolerate close to it (proximity partners) increased after the hurricane.

- More proximity partners and stronger links with them were each associated with an approximately 40% lower mortality after Maria struck. Beforehand, there was no relationship between proximity partners and mortality.

- The increased tolerance for other monkeys nearby was seen not only when they were squeezed together in the limited shade in the hot afternoons but also during the cooler parts of the day, suggesting that the overall nature of the macaques’ social relationships had changed.

Humans look like being too stupid or selfish to prevent a climate catastrophe but maybe, just maybe, our cooperation genes, which have for the last two million years been largely responsible for the success of the human race, will spring into overdrive, If so, those humans who are left might learn to work together even more strongly to try to ensure that our species doesn’t die out completely. Those who regard the long-term survival of humans as important can hope for and work towards that outcome anyway.

Seville in southern Spain gets very hot in summer and shade is at a premium

More vegetation means lower temperatures

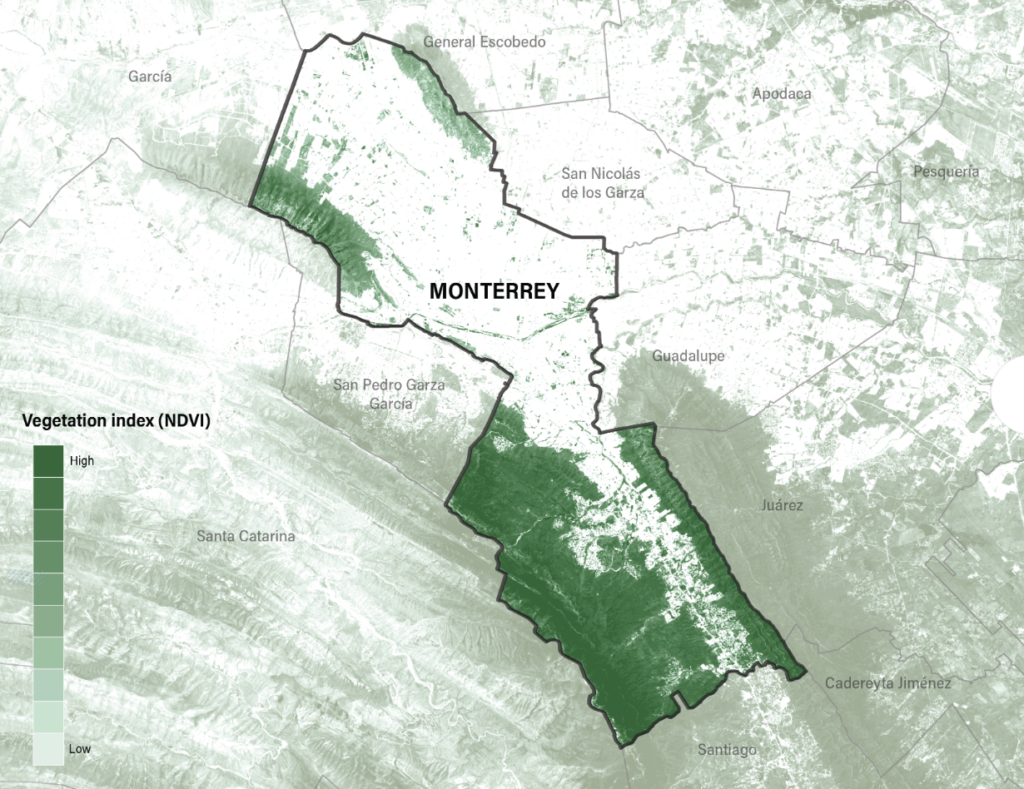

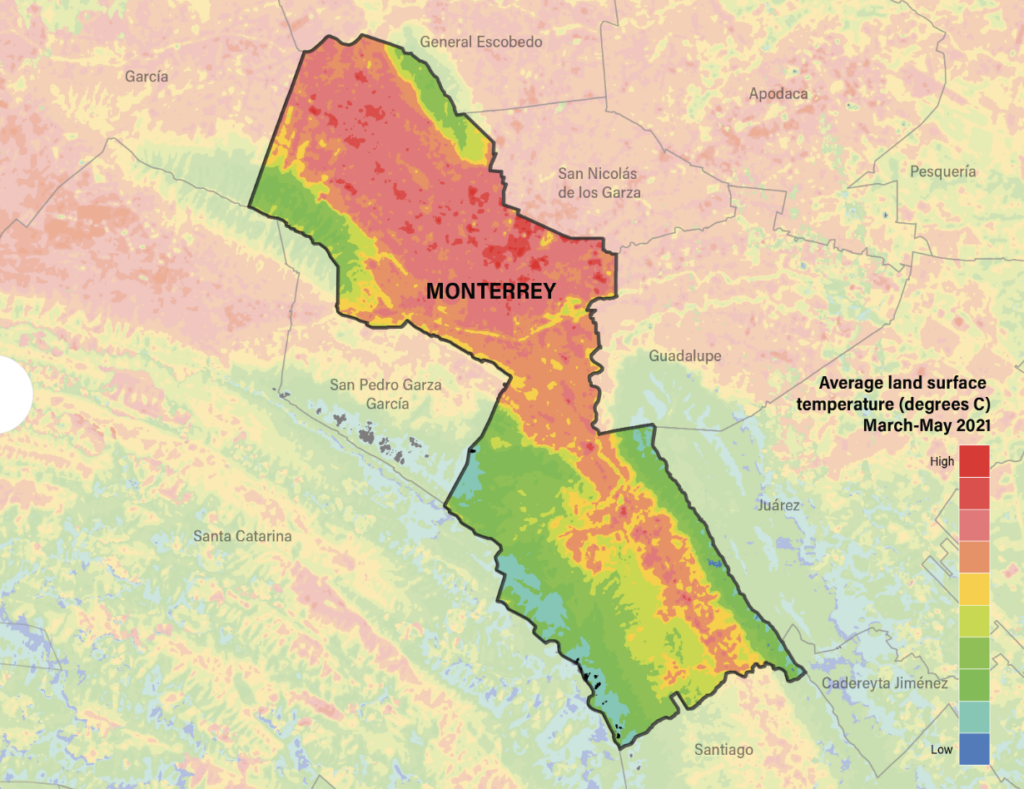

The two maps below show measures of vegetation cover (the greenish map) and average land surface temperature (pinkish map) for Monterrey, CA in March-May 2021. Across the whole municipality there was an 11oC temperature difference between the hottest and coolest districts, and across the mostly urban districts there was a difference of 6oC.

If you want to stay cool as the temperature rises, make sure you’ve got plenty of trees and shrubs in your gardens, streets and parks, and replace those dark, heat-absorbing roofs and other surfaces with lighter reflective ones.

SDGs. Remind me what they are

The United Nations’ seventeen SDGs, or Sustainable Development Goals, which replaced the Millennium Development Goals in 2015, have had a very low profile in Australia. So it is not surprising that the 2024 report on progress towards the 2030 deadline for achievement suggests that Australia’s end of term report might say ‘has great capacity but makes little effort, could try harder’.

The progress of 167 of the nations that are signed up to the SDGs has been scored on an index of 0-100. Finland tops the ranking with 86.4, closely followed by a host of European nations. Japan and Canada are the only non-European nations in the top 25. Southern Sudan brings up the rear with 40.1.

Australia ranks 37th with a score of 76.9, not too bad but we are on track to meet only one goal, Gender equality. Few P&I readers will be surprised to learn that our lack of achievement on the following goals has dragged down our overall progress score: Reduced inequalities, Responsible consumption and production, Climate action, Life below water and Life on land.

Of the 167 nations assessed, 158 scored more than 50/100 but only 16% of the 169 targets within the 17 SDGs are on track to be met. Many of the remainder are showing limited progress or even going backwards. The targets related to food and land systems are going particularly badly.

The unavoidable conclusion is that globally most SDGs will not be met by 2030 and this has led to calls for a focus on fewer goals and targets. An opinion piece in Nature strongly disagrees, arguing, rightly in my view, that the various global crises are interlinked and only a holistic and global approach to solving them will work. The authors suggest that the SDGs should remain at the centre of global policy agendas (remain? it isn’t clear to me that they are currently) and that the framework should be extended to 2050, with interim targets for 2030 and 2040.

Suggested targets for Climate action (SDG 13) are that global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions should be reduced by at least 58% by 2040 compared with 2019 and that the world should be net zero GHG (not just CO2) emissions by 2050, with fewer than 5 giga tonnes of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) emissions per year. The authors are clear that a price on carbon is essential.

For Life below water (SDG 14) and Life on land (SDG 15), a target of halting the global loss of biodiversity by 2030 is proposed.

Central to the authors’ proposals is a strengthening of global governance, including financial, systems, and a shift from countries endlessly negotiating about problems to delivering solutions and strong enforcement mechanisms. The last element is the one that will be most vigorously opposed by governments and the private sector. Cross-border impacts that hinder another country’s SDG progress (wealthy countries are particularly at fault here) must be eliminated.

The authors stress the dangers for future generations of exceeding planetary boundaries and creating unmanageable, irreversible damage to the natural systems that support life on Earth. Particularly cogent is their comment that, ‘A new economics of the common good is needed, too — for setting shared goals and working out how to achieve them. This involves cross-cultural respect and cooperation, the cultivation of civic virtues and defending the dignity of the socially, politically and economically marginalised — with not just words but also policies and collaborations involving government, business, workers and civil society. Diverse voices and sources of knowledge must be brought to the table to discuss what it means to co-create a just and sustainable economy’.

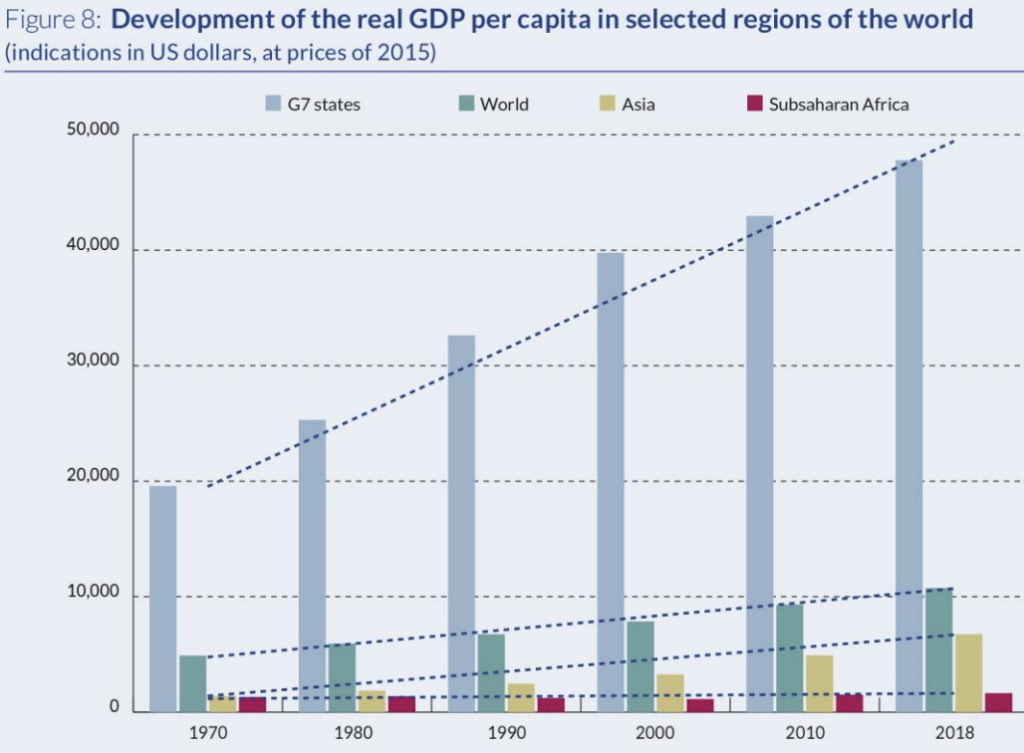

Climate change and the other pressing environmental challenges are not just ‘material’ problems that can be solved with scientific evidence and the application of cutting-edge technology. They are also social and moral problems that require simultaneous attention to social justice and democracy. How much longer can we expect the peoples of Sub-Saharan Africa to meekly accept situations such as this:

In case you missed it, here is a link to the article by Jeffrey Sachs in last Tuesday’s P&I about the SDGs, specifically five challenges that can be solved only by global cooperation and the forthcoming Summit of the Future. I’d add a sixth challenge: better models for the delivery of true democracy throughout the world.

More shady characters

New Delhi, May 2024

Muslim pilgrims at the Jabal al-Rahmah, Saudi Arabia, June 2024