Explaining the Gaza genocide: Settler colonialism in Palestine

December 8, 2023

In a settler colonial state, the indigenous population has to be physically erased because they are an ongoing reminder of the violence and injustice that occurred at the foundation of the political community. Their continuing existence constitutes a legal and political challenge to the states legitimacy.

It is therefore crucial that military resistance to the state by indigenous groups is de-politicised and instead seen as the behaviour of irrational and violent groups consumed by hatred, bigotry and racism: fanatics and extremists with dark hearts. In some cases it is suggested that the perpetrators are less than human, deserving of removal or extermination.

Ascribing the term terrorists to those who violently challenge the legitimacy of the state or colony, especially its existing borders, is designed to shut down any discussion of their political claims, grievances, nationalist aspirations, and therefore the possibility of a negotiated settlement of the conflict. The Portuguese, the British, the Belgians and the French all adopted this strategy in the face of growing demands for independence within their colonial territories. In almost every case they were unsuccessful.

The process of demonising those demanding self-rule and national liberation not only had to steer clear of any consideration of a groups political objectives, it also had to deny that their resistance was a display of anti-colonial violence.

Thats because the second half of the twentieth century saw the collapse of European empires and a wave of revolutionary upheavals resulting in a trebling of the number of independent states in the world. De-colonisation, as a pre-requisite to an act of self-determination, became both a norm in international politics and the title of a permanent committee at the United Nations which sponsored the transition of colonial territories to independent actors.

This is the context for the Israel-Palestine struggle which has been underway since 1948. For most of that time the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) was considered by the Israeli government as a terrorist organisation challenging the political legitimacy of the Jewish state. Its leadership was regularly assassinated or driven into exile.

However, since the secular PLO as the Palestinian Authority (PA) became a collaborative local authority in the West Bank which effectively manages the occupation of the territory on Israels behalf, it has been Islamic group Hamas in Gaza which has taken on the mantle of an existential terrorist threat in the eyes of Israel.

In light of the deadly attacks by Hamas on 7 October, 2023, it is worth examining the nature of settler-colonial states and the extent to which Israel fits the profile. In particular, it is important to ask whether it is Israels status as a settler-colonial state that explains the nature of its response to Operation Al-Aqsa Flood, specifically its most recent attack on Gazas civilian population.

Settler-colonial states According to Illan Papp, who drew on the work of the French Marxist Maxime Rodinson and other scholars whom he describes as a new movement in intellectual and activist approaches to Israel-Palestine, Zionism was a settler colonial movement, similar to the movements of Europeans who had colonised the two Americas, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand Thus one can depict Zionism as a settler colonial movement and the Palestinian national movement as an anti-colonialist one.

Papp argues that settler colonialism can be distinguished from classical colonialism in three key respects.

First, settler colonies rely only initially on the empire of origin for their survival and the settlers themselves may not belong to the same nation as the imperial power which supports them (eg South Africa and Israel, but not Australia and New Zealand). Often they separate from the empire, redefining themselves as a new nation, sometimes by concession (eg Australia), negotiation (eg New Zealand), and at other times via wars of national liberation against the motherland (eg the United States and South Africa)."

Secondly, settler colonialists seek a homeland already inhabited by others who need to be controlled (eg Palestinians), removed (eg Palestinians) or exterminated (eg Australia and the United States). Often the settlers claim the land is theirs by divine, moral or historical right, or because as a higher civilisation, they will make more productive use of it. This may lead to cultural assimilation in some cases and, in others, the genocide of the indigenous population.

Thirdly, settler colonialism focuses on the control of land rather than the extraction of resources, which is more commonly associated with classical colonialism.

This third point is crucial in explaining the empathetic relationship between settler colonial societies such as Australia and Israel. According to critical anthropologist Patrick Wolfe, the insatiable appetite for land leads settler colonialists to a logic of elimination in their attitudes and behaviour towards the indigenous populations they encounter, displace and annihilate. According to Wolfe, elimination is an organising principle of settler-colonial society [which] destroys to replace it erects a new colonial society on the expropriated land base invasion [therefore] is a structure not an event.

Wolfe claims that whatever settlers may say and they generally have a lot to say the primary motive for elimination is not race (or religion, ethnicity, grade of civilisation, etc.) but access to territory (emphasis added). Territoriality is settler colonialisms specific, irreducible element [because it] always needs more land.

The claim to land can be dressed up in many ways. A superior people will make better use of it, it will help to civilise and evangelise backward natives, the land was vacant or the indigenous population is considered unworthy, sub-human, and therefore unable to bear legal rights to it.

In the case of Israel, settlers claim to have been on the land primordially and were merely returning home after an extended absence of occupancy. This assertion is frequently combined with an exclusive biblical claim invoking a divine promise of land, considered an ancient moral right, a mandate and a duty to displace the indigenous population of Palestine:

Although the Zionist conquest of Palestine has many precedents (eg the European settlement in North America, or the British one in Australia and New Zealand), it had several unique features. The displacement took place within decades rather than two or three centuries. Secondly, the Zionist colonisation took place after the heyday of European colonisation, at a time when the European colonising nations were beginning to respect the right of self-determination of indigenous populations and when the very notion of colonisation was beginning to break down. Thirdly, most of the Zionist colonisation has taken place in an age of mass communications, although until recently, it has managed to portray itself as an innocent victim reaping its just rewards. But, most distinctively, the Zionist colonialist enterprise has widespread religious support, Christian as well as Jewish, and in most theological and religious circles is viewed as being consistent with biblical prophecy, or at least being no more than what the Jewish people deserve in virtue of the promises of God outlined in the Bible.

With the Torah as a legitimating charter for land entitlement, and the unprecedented genocide of European Jews during World War Two, the arguments for an exclusively Jewish homeland which were first made in the late nineteenth century, became an almost irresistible reality by the middle of the twentieth century. Furthermore, a return to a newly created Jewish homeland may have legally entitled those without any familial or historical connection to the holy land to migrate to it and dispossess the exiting indigenous population. It remains a powerful, legitimising ideology for Israel.

As is normally the case with settler colonial societies, however, the pursuit of Zionism, which was originally an overwhelmingly secular movement but has been more recently defended on religious grounds, came at an enormous cost to the indigenous population: the Palestinian Nakba or catastrophe. Dispossession, exile, cantonment, separation, occupation, cultural repression and death followed a familiar pattern set elsewhere.

According to Wolfe, Zionism had additional unique attributes as a settler colonial movement. Unlike in Australia and the US where there isnt an archive of detailed accounts of the need to eliminate their respective indigenous populations, Zionism presents an unparalleled example of deliberate, explicit planning. No campaign of territorial dispossession was ever waged more thoughtfully. It was open and explicit.

Secondly, whilst American Indians and Australian Aborigines were belatedly granted citizenship and forms of native land title, Zionism rigorously refused, as it continues to refuse, any suggestion of Native assimilation [and] constitutes a more exclusive exercise of the settler logic of elimination that we encounter in the Australian and US examples.

This has led directly to unique distinctions between citizenship and nationality (citizens and natives) in Israel, granting superior rights to immigrants, both actual and potential, than to those remaining indigenous and occupied populations. It also raises serious questions about the democratic nature of a state which maintains these distinctions: which human rights groups have described as constituting apartheid. According to Wolfe the distinction must be preserved because the Jewish state cannot live with the Palestinians and it cannot live without them, a necessary case of bonding by exclusion.

Thirdly, and unlike the Australian and US experiences, immigrants to Israel were not overwhelmingly sourced from a one mother country. From its beginnings, Zionism was an internationalist movement that consciously avoided confinement to a single metropolis .

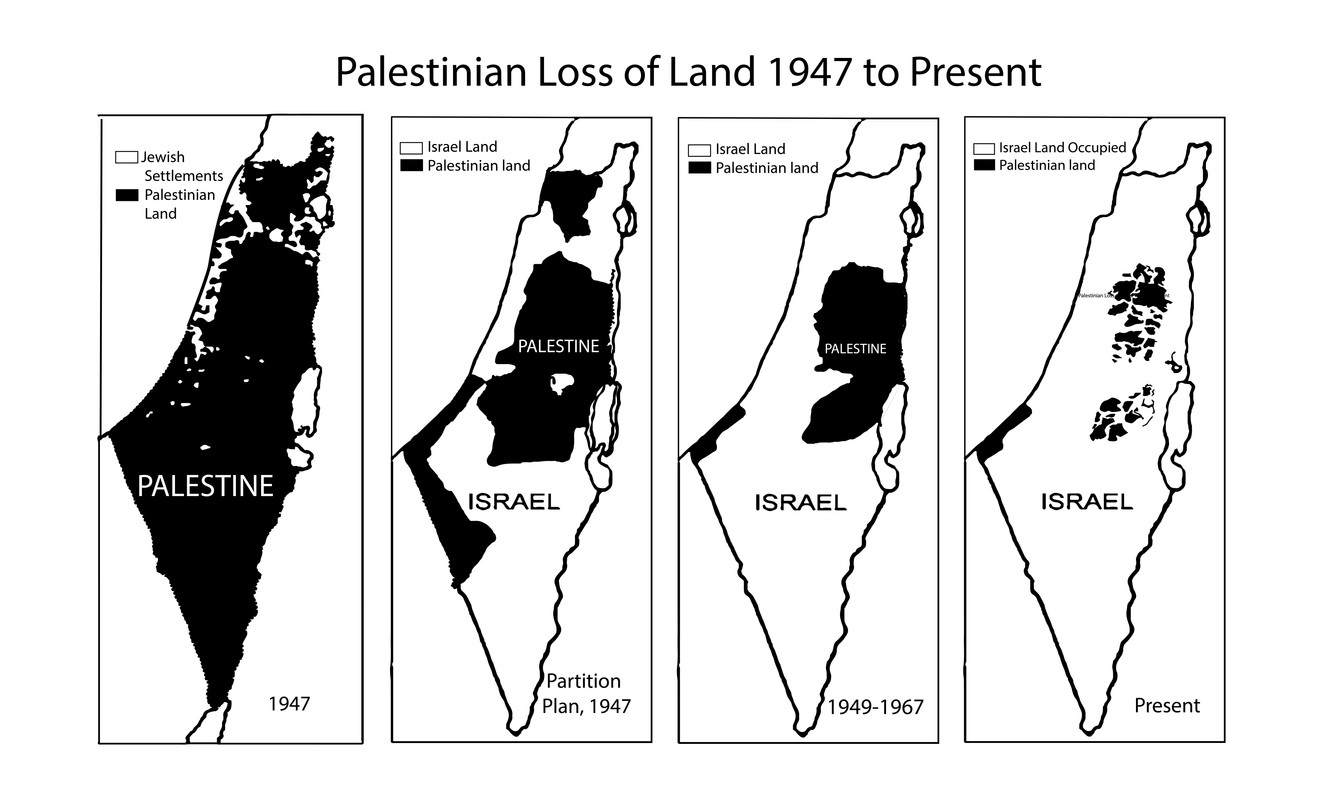

Finally, prior to the end of 1947, Zionism was conspicuous for its policy of purchasing Native land in at least notional conformity with the domestic laws of the current local power. This was fundamentally different to the colonisation of Australia which began in 1788, though it was almost entirely abandoned the following year when the state of Israel was proclaimed.

What do these parallel experiences tell us about Australias consistent support for a colonial project in the post-colonial period?

The first point to make is that within Australias mainstream political narratives, there is no mention of Israels colonialism or colonisation of Palestine, let alone genocide or apartheid. Despite universal acknowledgement of Australias own colonial history, and an increasing understanding of its devastating effects on the Aboriginal population, there is no recognition by either of the major political parties that the creation of the state of Israel in 1948 and the events which followed constituted a comparative experience Like an unmentionable pejorative term, Israels colonial occupation of Palestine has been defined out of existence in Australia, despite its currency in debates in the Levant.

A similar double standard applies to indigenous opposition to colonialism. In Australia, largely as a result of the work of historian Henry Reynolds, accounts of aboriginal resistance to the European invasion of Australia and the frontier wars that occurred have become mainstream historiography in the country since the 1980s. Any suggestions that this resistance constituted terrorism have long disappeared from public discourse. In fact the challenge for historians of colonial Australia has been to gain acknowledgement that organised indigenous resistance took place at all. The contrast with mainstream depictions of Palestinian resistance to Israeli colonialism could hardly be greater.

Notwithstanding other factors at play, including heavily resourced and influential lobby groups, relatively high levels of post-war migration by holocaust survivors and bipartisan party political support, the shared settler-colonial experience is a powerful explanation of why Australia, the United States and Canada have been so supportive of Israel or, conversely, why they have been so unsympathetic towards Palestinians. The approach towards an occupied and colonised people mirrors the sentiments and treatment of their own indigenous populations, which in the case of Australia and the United States was much worse than Israels.

If you regard indigenous people as irredeemably violent, inexplicably resentful and ungrateful for being civilised by a superior white culture, and incapable of accepting their fate, why respect their rights or treat them as equals? It is much easier and more effective to treat them as religious fanatics, primitives, terrorists, a barrier to statehood and an ongoing security threat to people who do matter. This goes much deeper than internalised racism. As Wolfe reminds us, this is first and foremost about entitlement to land.

Compare the indifference towards hundreds of Palestinian deaths at the hands of the IDF drones and snipers in Gaza and the deaths of civilians during Operation Cast Lead, Operation Pillar of Defence and Operation Protective Edge with public expressions of outrage and sympathy whenever a Katyusha rocket kills or injures an Israeli citizen: the extent to which racism and colonialism have been internalised in this settler colonial society is soon revealed.

The legal right to resist the confiscation of land and colonial occupation (including by the use of military force), which in Australia proved futile, is replaced with the more ideologically effective terrorism narrative in the case of the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Why did the the 7th October incursion generate global expressions of outrage and headlines around the world, including saturation media coverage in the West, compared with Israels regular mowing the lawn attacks on Gaza over the last twenty years? The answer seems obvious. On this occasion, around 1200 Jews were killed. In previous conflicts with Gaza, very few Israeli citizens lost their lives.

Paradoxically it was therefore the ethnicity of the victims which rescued the Palestine question from increasing media and political obscurity: presumably this was one of the motives for the attacks which Hamas had in mind.

It is not true to suggest that the civilian population of Gaza is suffering as a result of Israels conflict with Hamas. They are being deliberately targeted and punished as part of the ethnic cleansing of the strip. Up until the ceasefire which saw an exchange of prisoners and hostages, Hamas appeared to be relatively unscathed.

Civilians who survived Israels onslaught have seen their homes destroyed and are now watching as outsiders discuss, without any consultation, where they will be re-settled. They may be driven from their homeland again as they were in 1948, possibly into Jordan, Lebanon or the Sinai Desert. Israeli MKs have discussed negotiating with other states to accept clusters of Palestinians on the understanding they will never be allowed to return home. The common theme is very clear: destroying Hamas is the pretext for vacating, or more accurately ethnically cleansing the entire Gaza strip of its inhabitants.

The logic of elimination, as Wolf terms it, means this conflict is primarily about territory, and Hamass attack on 7 October gave Israel the perfect excuse it needed to realise long held territorial ambitions: Eretz Israel. The quest for lebensraum, or additional living space, is textbook settler-colonialism.

It would appear that settler-colonial societies have a common appreciation of the conditions and challenges they face, and similar attitudes towards indigenous peoples. This ultimately shapes the policy framework they construct towards each other. As Noam Chomsky argues,

The movement that developed (ie the Jewish settlement of Israel) is a settler-colonial society. Like the USA, Australia, the Anglosphere. Israel is one of them. Its not a small point. If you take a look at the international support for Israels policies, its of course primarily the USA, but secondarily its the Anglosphere. Australia, Canada I suspect there is a kind of intuitive feeling on the part of the population. Look, we did it, it must be right. So they are doing it, so it must be right. The settler-colonial societies have a different kind of mentality. We did exterminate or expel the indigenous population so there has to be something justified about it superior civilisation or other ideas. Israel has had the problem that its a twentieth-century version of a seventeenth through nineteenth-century colonialism. Thats the problem.

An earlier version of this article can be found in Scott Burchill, _Misunderstanding International Relations (_Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore 2020).