Fighting coercive control: Why we can’t police our way to safety

November 19, 2024

Last week the state of South Australia moved another step closer to criminalising coercive control, with the bill passing through the House of Assembly on its way to the Legislative Council.

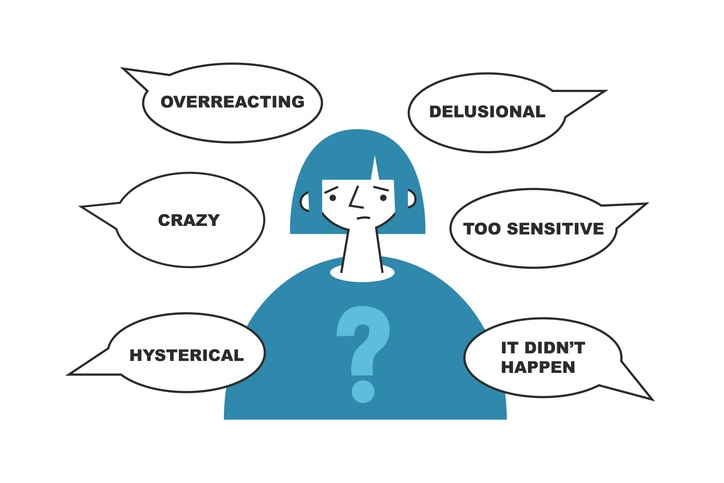

South Australia’s Criminal Law Consolidation (Coercive Control) Amendment Bill 2024 was introduced by the Labor Government in August this year. This legislation aims to criminalise coercive control, recognising it as a serious, non-physical form of domestic abuse that includes emotional manipulation, isolation, and financial control. If passed, the law would impose penalties of up to seven years in prison for people who perpetrate these controlling behaviours. The Attorney General states that the drafting of the bill involved extensive consultations with community groups, including First Nations representatives, LGBTQIA+ advocates, and multicultural and disability communities, presenting a broad understanding of the diverse impacts of coercive control in intimate relationships.

The proposed law is part of a broader national push to address and prevent domestic violence-related harm, informed by evidence that coercive control is often a precursor to physical violence and domestic homicides. While the availability of data on coercive control in Australia is limited, the New South Wales Domestic Violence Death Review Team found that coercive control was present in 97% of intimate partner homicides in NSW between 2000 and 2018. Coercive control is clearly a problem that we must pay attention to, and carceral feminists have made sure that it has remained on the legislative agenda, despite abolitionists objection to its criminalisation.

Let me start by acknowledging that we are in the middle of a crisis. 11 Aboriginal women have been killed since June this year, and the total number of women killed by intimate partners stands at 81 just this year. However, while white feminists are readying themselves to take to the streets and understandably protest these killings, I feel compelled to remind them that this is not a new crisis for the Aboriginal community. The disappearing and killing of Aboriginal women began the day that the First Fleet arrived on these shores, and it has not ended. In fact, Aboriginal women have been screaming their objections and resistance into, what has felt like a colonial void, for more than two centuries, with barely a whisper let alone of a roar of solidarity from the white sisterhood.

As an abolitionist and a victim-survivor of coercive control, I have vocally opposed the criminalisation of coercive control. This is not because I do not recognise the seriousness of the violence, or because I condone it. Rather, I am opposed to extending the role of criminal law enforcement in our country, and because I do not think that police, courts, or prisons represent safety and justice for everyone in this country. I believe that a carceral response to gendered violence whereby we typically focus on raising arrest rates, securing convictions, and imposing longer prison sentences for people who perpetrate violence, will not necessarily protect all survivors, nor prevent further abuse.

What we, as abolitionists, predict is that these kinds of policies, such as criminalising coercive control, while well intentioned and designed to safeguard women, will in fact, paradoxically lead to a rise in the arrests of women themselves. As it is, victim-survivors are frequently arrested alongside or instead of their abusers, especially when they defend themselves physically. Take Ms Dhu for example. Ms Dhu was killed in custody after being arrested for outstanding warrants when police were called to her property in response to her partner breaching an AVO. These kinds of preventable tragedies happen because many victim-survivors do not fit the ‘ideal victim’ profile that the legal system expects, complicating the distinction between ‘victim’ and ‘perpetrator.’ This issue is a particular problem for Aboriginal women who are frequently treated as the perpetrator, and subsequently criminalised for fighting back or not presenting to police as the ‘ideal victim’. While the Minister for Women and the Prevention of Domestic, Family and Sexual Violence, Hon. Katrine Hildyard has acknowledged the deep mistrust held by Aboriginal women toward government authorities due to the intergenerational trauma of colonisation and dispossession, I remain unclear how exactly this bill will prevent misidentification of victim-survivors as primary aggressors, nor the arrest of victim-survivors for retaliatory offences, as the Honourable Minister promises. Misidentification is a real problem, but it is only one of the many problems we have highlighted with the criminalisation of this form of abuse.

The criminalisation of coercive control will require an increased police presence in victim-survivor’s lives, further entangling us in the criminal legal system For myself as a criminalised woman, I know firsthand the reasons many of us don’t turn to the police. My own history with law enforcement, and the ways that police represent a threat rather than a source of safety, deterred me from reporting the abuse that I suffered. This decision, however, wasn’t accepted by everyone involved in my support network. A social worker viewed my choice not to report to the police as a failure to protect myself and my children, implying that ‘real’ safety could only be pursued through the criminal legal system. Despite me leaving the abusive relationship and seeking support through a domestic violence service, the social worker still included my decision not to report the abuse to the police in their report to the child abuse report line. They regarded the decision as me not holding my aggressor responsible for his choice to use violence. I, like many other women in my situation, know that the legal system, a deeply carceral institution, is not safe for everyone—it can be deadly for people like me and can exacerbate harm, especially in Aboriginal communities. The reliance on policing and criminalisation to address gendered violence doesn’t just overlook the needs of women like me; it puts us at risk. And a side point worthy of mention is that were I to rely on police and prisons to bring the perpetrator to justice, and that perpetrator was Aboriginal I could well be complicit in imposing a death sentence upon them, given the high rates of Aboriginal deaths in custody in this country.

In the broader domestic violence sector, carceral solutions dominate, often with little room for alternatives that could genuinely protect and support all survivors, particularly criminalised and Aboriginal women. The reliance on the colonial legal system risks creating two tiers of support: one that serves those who feel safe engaging with law enforcement, and another that leaves the rest of us out in the cold. Feminism more broadly and the domestic violence sector, including frontline staff, seem unable to operate or imagine solutions outside the logics of the carceral state, leaving us reliant on systems that prioritise punishment over real care, support and protection; when we could be exploring and investing in alternatives that respect the safety and humanity of all victim-survivors.

An abolitionist approach to coercive control would focus on addressing the root causes of abuse, rather than merely reacting to its symptoms with punitive measures. Instead of relying on carceral systems that may offer temporary relief but often perpetuate cycles of harm, abolition demands of us to dig deeper into the conditions that create and fuel violence. It is about examining why abuse happens in the first place—and recognising that it’s driven not just by individual choices but by structural and systemic forces that normalise and even incentivise violence.

At the core of this perspective is an understanding that poverty, unemployment, and lack of access to resources fuel the dynamics of abuse. But beyond these immediate factors, coercive control is also tied to larger, entrenched systems of racial capitalism and the patriarchy. These systems thrive on inequality, generating disparities that perpetuate vulnerability, dependency, and oppression. For example, poverty can make it harder for survivors to escape abusive relationships when they lack safe housing or income to sustain themselves independently. Meanwhile, racial capitalism and patriarchy enforce hierarchies that normalise control, dehumanise marginalised people, and keep certain communities—especially criminalised Aboriginal women—trapped in cycles of harm.

Without addressing these underlying forces, any response to violence risks being mere window dressing—a large band-aid covering a festering wound. Criminalising coercive control might provide an illusion of safety, but it doesn’t dismantle the structures that allow coercion and control to exist in the first place. Instead of focusing on more arrests and longer prison sentences, we need to invest in community-centred solutions that address material needs and shift power to victim-survivors and communities, not to punitive systems.

This requires a radical rethinking of support systems from the ground up: creating safe, affordable public housing, real and sustained job opportunities, accessible mental health services, and social support that can prevent abuse and provide victim-survivors with the real choice to leave harmful situations. It means working to dismantle the racial and economic inequalities that make certain groups disproportionately vulnerable to both violence and state control. We can’t police our way to true safety—it will require us transforming our communities into spaces where everyone has what they need to live free from violence.

An abolitionist approach to coercive control, then, is about building systems of care and solidarity that replace cycles of control with ones of community and healing.

In pushing for the criminalisation of coercive control, the state and carceral feminists may claim to be advancing safety for women and survivors of domestic abuse. But real safety, especially for those of us most vulnerable to both interpersonal and state violence, cannot come from the same institutions that criminalise, surveil, and punish us. We must resist the easy answers and empty promises offered by the criminal legal system and, instead, demand the systemic transformation that abolitionists envision. Addressing the roots of coercive control means ending the conditions that perpetuate poverty, racial capitalism, and patriarchy—building a society where resources, support, and care are accessible to all. Only by investing in community-driven solutions, supporting victim-survivors on their own terms, and dismantling systems of control can we create a world where people are safe not only from abuse but from the institutions that have historically failed us. The work of real safety, accountability, and healing will not be found in prison cells or police reports but in communities that refuse to leave anyone out in the cold.