From genocide to resilience: The Crimean Tatars' struggle for justice

October 4, 2023

For nearly five decades, the Crimean Tatars tirelessly campaigned to return to their historical homeland in Crimea. Yet, for many political analysts writing about Crimea today from a critical perspective, the historical facts remain sadly unknown.

As a representative of the indigenous people of the Crimean Peninsula, a Crimean Tatar whose sole homeland is the Crimea, I cannot remain silent regarding an article in Pearls and Irritations penned by Graeme Gill, titled “Crimea and Conundrums.”

This article reflects the Soviet-Russian narrative in history, brimming with myths strategically woven by Russians to justify the genocide against the Crimean Tatars, as well as to bolster Russias claims in support of its illegal annexation and occupation of Crimea. Such distortion of history is also deployed to support the idea that the current ethnic Russian majority on the peninsula has a right to separate from Ukraine.

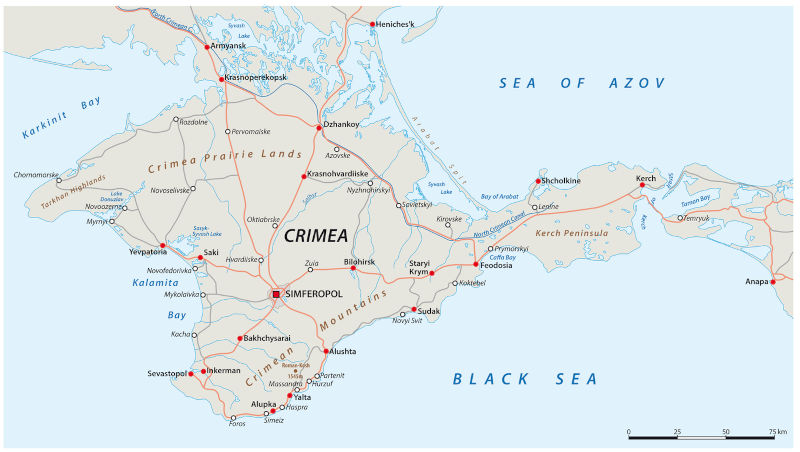

The Crimean Tatars are a nation that has evolved on the peninsula, complete with its own system of governance and national symbols, including a coat of arms and a flag. The very name “Crimea” has Turkic origins, translating to “stronghold” or “fortress.” Prior to the unlawful first annexation of Crimea in 1783, Crimean Tatars constituted approximately 80 percent or even more of the peninsula’s population. They were reduced to a minority due to Russian policies spanning more than two centuries targeting this people.

The author of the article questions the Crimea’s affiliation with the Crimean Tatars, prompting me to wonder, “Where does my homeland belong, then?” Furthermore, the author makes significant errors in defining the Mongols. Mongols are a distinct ethnic group, while Tatars are another. Within the Golden Horde, various Turkic peoples coexisted alongside Mongols. Russian historiography, alongside the Russian historian P.N Naumov, amalgamated these diverse Turkic groups into a single category known as “Mongol-Tatars,” which is an incorrect classification. This period marks the commencement of another distortion of the historical past of the peninsula.

The Golden Horde exerted a profound influence on the ethnogenesis of Eastern Europe and Asia, including Russia and Ukraine. Notably, when the Golden Horde arrived in Crimea, it marked the beginning of the Golden Horde’s disintegration. By then, the Golden Horde had already been absorbed by Turkic peoples. Furthermore, Crimea had been home to Turkic and European tribes prior to these events, forming the foundation of the Crimean Tatar nation.

Consequently, historical narratives fabricated by Russia about Mongols surrounding Crimea are progressively losing relevance with each passing year.

People who meet Crimean Tatars will notice that many resemble in appearance other European peoples, underscoring the influence of other European tribes that actively participated in the ethnic formation of the Crimean Tatars, such as the Goths, Genoese, and Greek colonies, which at various times settled in Crimea. The Crimean Khanate itself stood as one of the formidable Eastern European states, known for its cultural, architectural, and intellectual contributions, expressed through the works of Crimean Tatar philosophers, reaching far beyond Crimea’s borders.

I would also note that the Crimean Tatars have been recognised as indigenous by the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Peoples, the European Parliament, the Ukrainian Parliament and several countries around the world.

Graeme Gill, in a comment implying that Crimean Tatars are not indigenous, cites the 1897 census, claiming that Crimean Tatars constituted around 35 percent of the population. However, how can one overlook the systematic wars that occurred within Crimea’s borders? The unlawful annexation of Crimea in 1783 and Russia’s brutal policies towards the Crimean Tatars led to their mass expulsion from their ancestral lands. Moreover, the consequences of the Crimean War of 1853-1856 had a significant impact on the Crimean Tatars, who consistently faced ethnic cleansing at the hands of Russia.

Even so, 35 percent was actually the biggest ethnic group (compared to 33 percent of Russians - and remember, many of the Russians were incoming military personnel and so on): why is this number not enough for proving that Crimean Tatars are the indigenous nation there and not some kind of foreigners?

In a comprehensive scholarly study conducted by Yamur Derin kten, an expert in the realm of Western travellers and their observations regarding the Russian incursion into Crimea, valuable insights emerge concerning the enduring and recurring nature of forced displacement experienced by the Crimean Tatars.

The migratory patterns, set in motion immediately following the Russian occupation, persisted for approximately 150 years and witnessed several distinct surges, most notably during the 19th century, with peak years occurring in 1812, 1828-1829, 1860-1861, 1874, 1890, and 1902. Post-1874, compulsory military service for the Tatars emerged as a significant factor contributing to their displacement. It is estimated that between 1783 and 1922, around 1.8 million Crimean Tatars were forcibly uprooted from their homeland.

This policy of ethnic cleansing targeting the Crimean Tatars endured for centuries, including their complete removal to Central Asia in the Soviet deportation of 1944, which resulted in the deaths of 40 percent of the Crimean Tatar population.

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Crimean Tatars actively began returning to their historical homeland. Prior to 2014, they constituted between 13 percent to 15 percent of the population. If not for the nine years since the second annexation by Russia in 2014, Crimean Tatars would have accounted for approximately 30 percent of the population today.

The process of returning to their homeland will not cease after the de-occupation of Crimea, and the returning Crimean Tatars will significantly bolster the indigenous population of the peninsula. However, after 2014, Crimea again began to be actively populated by citizens from Russia. According to various experts, from 600 thousand to a million Russians came to Crimea, a deliberate increase in the Russian population in Crimea. This is a violation of international law.

Graeme Gill writes: “a series of polls taken after the referendum by reputable polling companies Gallup, Pew Centre, and Levada Centre all showed overwhelming support for the decision to join Russia”. I strongly believe all this data is completely unreliable, since no one seriously believes in any polls taken in Crimea after 2014. Especially the Moscow-based Levada Centre. Even directly asking people if they agree to be “a part of Russia”, many answers will be positive because of fear of being persecuted by the FSB and other Russian forces.

In a poignant struggle against the unlawful annexation of Crimea in 2014, the Crimean Tatars find themselves once again contending with the violation of their rights in their homeland. Hundreds of Crimean Tatars are unjustly imprisoned in Russia facing sentences ranging from five to 25 years. Between 2017 and 2022, the Crimean Tatar Resource Centre documented over 7,000 human rights violations in occupied Crimea, with 5,613 of these incidents targeting members of the Crimean Tatar people. But despite the punitive policy towards the Crimean Tatars, they continue to fight.

Moreover, they are prominently represented within the Ukrainian government. Eminent figures like Emine Dzheppar, the First Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, and Tamila Tasheva, the Presidential Representative in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, proudly identify as representatives of the indigenous Crimean Tatar people. And the newly appointed Minister of Defence of Ukraine, Rustem Umerov, is a Crimean Tatar.

Overall, with full respect to the author, it is evident that even for scholars highly competent in political discourses around Russia, there is a lack of any deep insight into the history of the region.

Simply put, for many political analysts writing about Crimea from a critical perspective, the historical facts remain sadly unknown.

For nearly five decades, the Crimean Tatars tirelessly campaigned to return to their historical homeland in Crimea. They persevered through Soviet jails and hunger strikes to reclaim their rightful Homeland Crimea. They did it. They returned. No amount of pro-Russian narratives or attempts to obscure the genocide against the Crimean Tatars, under the guise of a Russian majority population, will deter this resilient peoples fight for their homeland - Crimea.