Grinding the axis

November 12, 2024

Axis is a four-letter word that should be banned or at least binned for the time being. The US uses the term in a distinctly hostile way, and now Andrew Shearer, Australia’s chief security adviser, has adopted the same language.

When the world teeters on the edge of uncertainty following the outcome of the US presidential elections, presaging fears of unimaginable catastrophes, all security chiefs should be ultra careful not to use such inflammatory language.

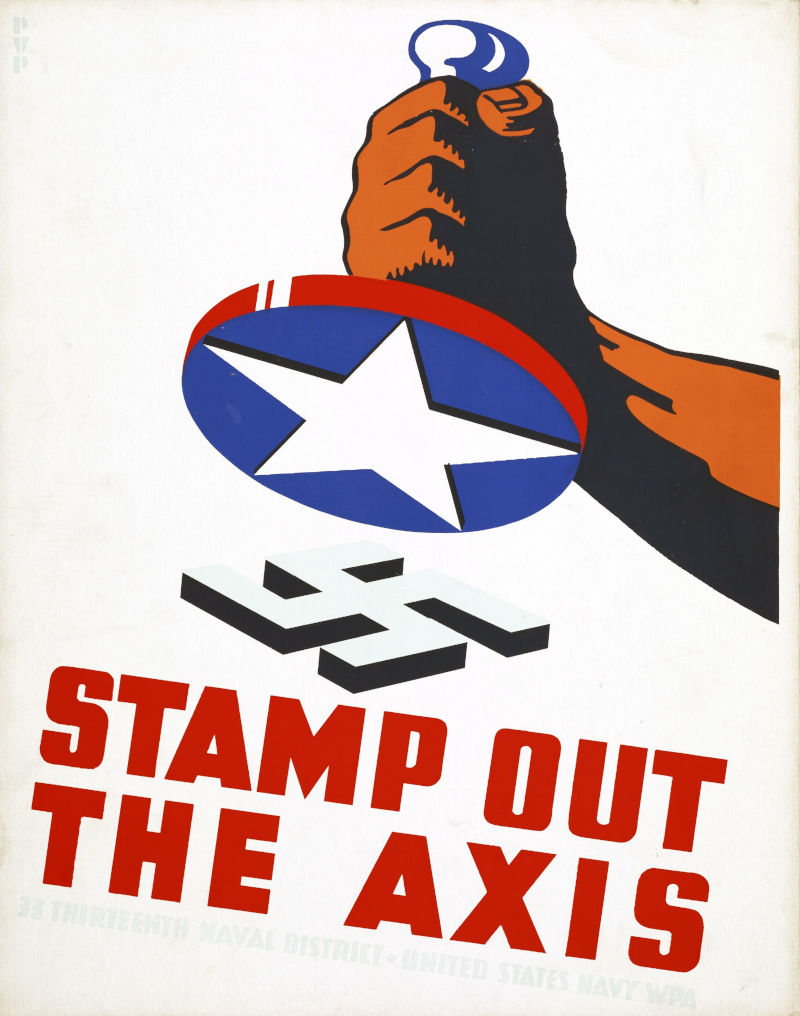

In plain speech, an axis is a straight line with a specific function that gives it importance, such as an axis of symmetry. In politics, the term “axis” came into general use to refer to the “Axis powers” of Germany and its allies in the Second World War. In that context, it made sense. Mussolini had proposed an alliance with Germany against France as an axis already in the 1920s. In the 1930s, Japan proposed a similar pact with Germany against the Soviet Union.

Memories of the War are still potent and colour thinking and action in the West. Politicians use the scenario of the rise of Hitler in the 1930s to drum up fear. In 2002 US President George W. Bush described Iran, Iraq and North Korea as the “Axis of Evil”. He implied that the three were linked in their support of terrorism and weapons of mass destruction. There was then and is now scant evidence of any alliance between the three and this was not the reason for the reference to an axis. The term was used to rally support for Bush’s “War on Terror.” We all know how much trouble that caused.

“Axis” then became a highly pejorative term. “Axis of Resistance” was thrown at Iran, Syria and Hezbollah. “Axis of Upheaval” is now levelled at China, Russia, Iran and North Korea. The term first appeared in April 2024 in an article by Richard Fontaine and Andrea Kendall-Taylor published in Foreign Affairs. The authors do not argue that there is a formal alliance or union between the four nations, but that they are united by their opposition to US primacy and an international order led by the West, by shared values of autocracy and neo-imperialism, and by economic, military and diplomatic cooperation. They are all bad guys, united in their villainy.

Despite questionable evidence, this perspective now dominates discussion of international affairs in the US. The consequence of such a view is that a dispute with any one of the four “Axis” countries is equally as significant as a dispute with any of the others. Russia must be resisted in Ukraine, Hezbollah in the Middle East and China and North Korea in North-East Asia. As set out in his latest book, Geoff Raby is one of the few who have cast doubt on the construction of what he calls “Chussia”. He highlights the deep-seated historical issues affecting relations between China and Russia. They undoubtedly share suspicion of the motives of Western powers and a desire to have an international order that allows more room for their interests. In the case of China, now a dominant economic power, this is surely overdue. They differ in their foreign policies, Russia pushing to establish buffer zones while China focussing on securing existing borders, as Shanshan Mei and Dennis Blasko argue in a recent RAND commentary.

Australian strategic policy leaders have now enlarged on the theme of “axis”. On 6 November Andrew Shearer, the head of the National Intelligence Office, told the Raisina Downunder Dialogue that China and Russia were the core of an “emerging axis” in a “profoundly troubling strategic development”. He cited as evidence Chinese “dual use assistance” to Russia, Iranian drones and North Korean missiles and troops and said, “This is one of the strategic challenges of our times.” It is ironic that Shearer chose to deliver this message to the India’s premier conference on geopolitics. Coming only days after a meeting on 23 October between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Xi Jinping and an announcement on disengagement and resolution of border issues. One wonders whether Shearer keeps up with his reading or if he is whistling up the ghost of Hitler and preparing the Australian electorate for another khaki election.

Not surprisingly, Chinese state media noted Shearer’s remarks and his reference to an emerging axis. An editorial in the Global Times on 6 October noted that China “did not create the Ukraine crisis, nor is it a party to the crisis”, and that China had been working to promote peace and encourage dialogue. The whole world hopes for a resolution of the war in Ukraine, for justice and peace. That includes China and China can surely play a role in bringing this about.

I guess it is too much to hope for an apology from Andrew Shearer, but at the very least, he should mind his language.