The elephant in the room - age and inter-generational equity

July 30, 2020

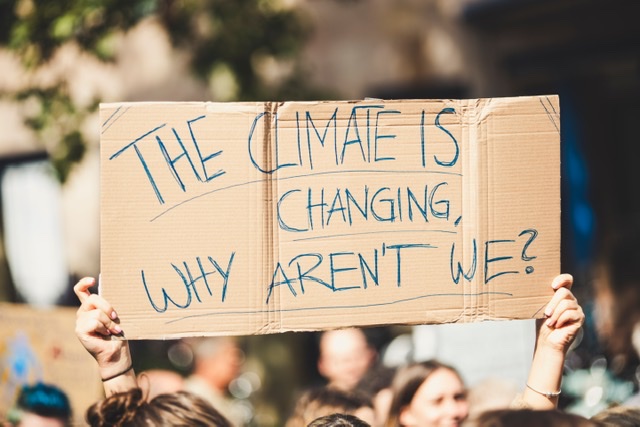

It is high time for a new inter-generational deal including a shift of decision-making powers as well as policy benefits towards the younger generations.

A few months ago, climate change alone seemed reason enough for a wider and very robust debate about inter-generational equity and the power the old and very old hold. The corona crisis has now added a new dimension to this issue. Calls for a new inter-generational deal may well become louder, and a unique opportunity to address other equity issues on the way may also arise.

From the perspective of younger people, it must appear that, whenever push comes to shove, political decisions are made for the benefit of the older half of the population at the expense of the younger half. More often than not, they are also made by the old or very old.

Whilst we are slowly awakening to the catastrophic impact government action against corona will have on the younger generation (in particular their employment prospects and their mental health), the young themselves have to date shown remarkable solidarity with the elderly and astounding constraint in expressing frustration and demands. Are the young really too saturated and soft (or lack resilience and need a hug as Ita Buttrose cynically said) and not angry and aggressive enough (as Michael Kirby recently suggested), are they simply still in shock or sedated by (finite) government welfare hand-outs; or is this only the calm before the storm? It may only be a matter of time before the younger generation(s) start demanding the right to determine their own future through more power and influence, as well as a radical reverse solidarity by the elderly through a gigantic re-distribution of burdens and benefits.

The ABC recently asked its audience in all seriousness if they find the 34-year old Finnish Prime Minister too young to be a political leader, yet not even the line-up of candidates in the US presidential election campaign has triggered a wider debate about the maximum age of political leaders.

I, like many around me born in the 1950s or 1960s, grew up with the firm belief that hardly anybody over 30 could be trusted. This was relatively straightforward and easily justifiable in (West) Germany at that time, given that most people of middle or older age who were still alive, had either been involved in war crimes or crimes against humanity, or had supported or been brainwashed by the Nazis in one way or another. However, the sentiment of a clear divide between the young (post-war) and the old (war and pre-war) generations was clearly present in many parts of the world and seems to be nowhere better captured than in Bob Dylans The Times They Are A-Changing. There was a widespread conviction within a large portion of the younger generation that those on the other side of the divide simply lacked the biographies, integrity, value compass and vision required to be entrusted with any significant role in shaping the future.

Trump v Biden is todays obvious case in point. Even if we are very generous and brush aside our suspicions that ones daily outbursts, mishaps and use of an active vocabulary of a 3-year old, and the others already proverbial gaffes, are evidence of underlying medical conditions, many of us would have (secretly) asked ourselves if either of them (or Sanders, Pelosi, or even Bloomberg or Warren for that matter) really has the energy, flexibility, sharpness and vision required for the job, or if they are simply too old. Would we happily see our children get in a car driven by any of them, fly our plane or perform brain surgery on us?

Even before corona, it has been argued that the world had crossed another Rubicon at some point in the past 20 years, in some ways comparable to the end of WWII. The technological revolution, climate change, the end of the cold war, and the rise of China mean that many truths, experiences and skill sets that were critical for shaping the second half of the previous century may now be almost worthless and more a curse than a blessing in the struggle to respond to the present environmental, economic, social and geopolitical challenges.

Corona has now exacerbated this development. Whilst only time will tell which country or government will be seen as having managed the health crisis well, the recovery management will be a totally different ball game (from a political, economic and social perspective) in a world we may not even recognise again. The age (not only in a biological sense but also as a matter of up-to-date vs outdated skill and mind sets) of our decision-makers will then matter even more.

Any person who was trained and at their professional peak in the previous century, would have already been challenged to throw a good portion of their experience overboard and find the energy to catch up on relevant technology and science and more or less reinvent themselves. In the political sphere in Australia, this has been particularly palpable in relation to climate change, our understanding and adaptation to the new roles both the US and China play in the new world order, and our response to the indigenous cry for a voice and constitutional recognition. When talking about the big issues that will determine our future way of life and our place in the world, most political leaders in our country seem to be so last century.

The situation is equally dire in the boardrooms of corporate Australia and many government, semi-government and not for profit organisations. The revelations of the Royal Commission into the Financial Services Industry and uncountable governance failures in all sectors have a lot to do with the fact that boards and other decision-making bodies often resemble more a retirement village than an engine room.

Accepting that 40 is the new 30, and that there is a grey area in which individual circumstances may determine whether a person is more rooted in the past or fit and energetic enough to shape the future, this may lead us to the rough assumption that the age of 50 could be the relevant divider. Lets then take into account that there are very good reasons to vest decision-making powers in women for longer (to allow for their longer life expectancy, make up for career breaks they experienced during one or more stages in their lives, and also address the widely agreed need to increase female representation in politics and boardrooms); and we may well have a case for a gigantic shift of any ultimate decision-making power to those who are under 50/55. This could well mean discouraging men from the age of 50 and women from the age of 55 to seek election to parliaments or councils, appointment to top jobs in the public sector or appointment to any executive or board positions; encouraging men from 55 and women from 60 to retire from any such positions; and encouraging those affected to dedicate their lives to advisory and voluntary/charity work and become a reliable resource for child care in their wider families. There would be almost no economic hardship involved with such a shift as almost everybody in this group is already well off (with the exception of the odd MP or Senator who cant live off $200k a year), and is not (or should not be) seeking or holding any such position for financial reasons (a study into the true reasons would be most fascinating, but I guess that ego, power and the desire to be/remain relevant would come out on top).

Even before the corona crisis, the inequity in the distribution of financial burdens, risks and benefits between the generations in Australia was obvious. Whilst the younger generation finishes their education highly indebted, has less chance of ever being able to afford their own home and is more likely stuck in casual jobs and the gig economy, the older generation has been enjoying social welfare benefits in form of the age pension (despite often living in high-value homes and having significant money in the bank) and franking credits (which are nothing else but a pension without any means test whatsoever), as well as ever increasing property values combined with generous capital gains tax exemptions and discounts.

The corona crisis has now increased this inequity dramatically. Whilst even the strategies pursued by governments (let alone the specific actions in response to the crisis) vary greatly between countries and even states and regions, it is fair to say that two facts are now widely accepted: (1) all actions governments have taken around the world have predominantly benefitted the elderly by saving their lives; and (2) the price for those measures is by and large (and will be for a long time) paid by the younger generation.

Throughout the crisis very few people have questioned the core principle that has driven government strategies, namely that all human life is of equal value and deserves the best possible protection regardless of how vulnerable a person is and how many years they would otherwise have left. However, if the application of this principle leads to disproportionate sacrifices of one group, then it is not only legitimate but imperative to set specific policies aimed at compensating the burdened group. This may mean shifting financial privileges from the protected group (the older generation) to the group that was forced to make the sacrifices (the younger generation).

In Australia, it is now time to adopt a younger generations first approach at many levels. The following policy changes would be an obvious starting point:

(1) HECS/HELP debts should be waived for everybody under 30. The often cited justification for the current loan system has been that university graduates and other beneficiaries of the system will have better jobs and earn disproportionately more during their lives. This argument has now gone out the window as some even predict that the younger generation of today may forever be a lost generation.

(2) Every parent must have free childcare options (including pre- and after school care) for the next 5-10 years. The cost of childcare has always been an enormous amplifier of social inequity, not only between the generations but also between the haves and have nots as well as the genders. Free childcare would give the most vulnerable (like young single mothers) a better chance to take advantage of job opportunities whenever they present themselves.

(3) Governments must subsidise apprenticeship and graduate programs (in the public and private sectors) at a large scale for the next 5-10 years. Such assistance would help younger people with an education to find a job in their profession and remain competitive during the economic crisis.

(4) On the revenue side of the equation, age pensions and franking credits could be (retrospectively) transformed into loans to the effect that they need to be repaid upon the death of the recipient and become a liability/debt of the estate. Such a step would ensure that the elderly are not worse off in their lifetime and do not have to change their financial plans and lifestyle (for example, the residential home and other quarantined assets would not need to be liquidated), but equity would be restored once a person is deceased.

(5) A substantial inheritance tax must become the centrepiece of a wider tax reform. It seems now widely accepted in the western world that wealth inequality is a much larger contributor to the widening gap between the poorer and the wealthier portions of the population than income inequality. Enormous amounts are passed on and inherited every year and a persons wealth is increasingly determined by how much they inherit. Taxing estates is therefore not only a logical way of contributing to inter-generational equity; it is also a legitimate means of combatting intra-generational inequity.

In addition to government policies, the young may also call on those elderly citizens who are already well off and still in (well-paid) jobs to make way for younger people by retiring earlier than planned, or waiving part of their salary to allow their employer to recruit an additional younger person, and so contribute to some form of payback.