Half a century: Australia, China and the United Nations

December 19, 2022

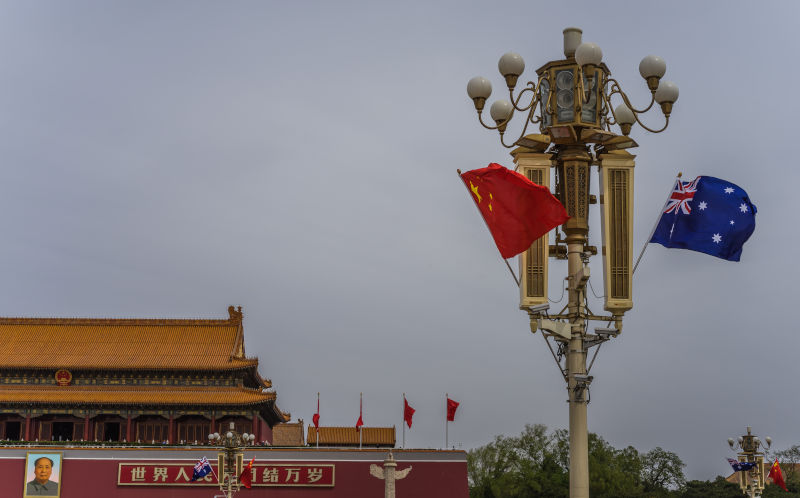

On December 21 it will be fifty years since Australia established diplomatic relations with China. The anniversary has already been marked by several events across the country. It is also prompting some reflections in the media. Many draw comparisons between 1972 and 2022, noting that in both years there were significant shifts in Australian foreign policy.

Immediately after his election win in 1972, Gough Whitlam built on his earlier visit to the Peoples Republic of China with a swift move to normalise relations. In an eerie replay of the events half a century ago, following this years change of government, Anthony Albanese has promised to look at measures to move forward together with China, and has described relations under the previous Morrison government as not healthy.

The comparisons are interesting but have limited value, because they fail to consider what extraordinary changes have taken place in the international environment over the decades. Their focus is only on the bilateral, not the multilateral relationships and not on shifts in the global strategic balance. Morrisons comments, that China had changed but Australia had not, ring hollow. Both have changed, and so has the whole world.

People forget, or perhaps they never knew, what the world was like back in the seventies. The decade was marked, not just by disco music, but also by a fundamental cultural shift. In 1972, Australian forces had been fighting in Vietnam for a decade, in a war led by the United States to contain the spread of communism. Across Australia, hundreds of thousands had joined moratorium marches. Even after the withdrawal of Australian troops, there was widespread negativity towards returning veterans. In the 1970s, most Australians still had vivid memories of World War Two and of how narrowly an aggressive Japan had been defeated in the Pacific. With this in mind, they were prepared to set aside Liberal Party concerns about a communist threat and instead look for ways to engage constructively with China, which they remembered had been our ally in the war against Japan.

Then, thirty years later, in 2001, came the shocking attack on New Yorks Twin Towers. President Bush named the perpetrators part of an Axis of Evil and the pursuit of these enemies led to Australian engagement in another decade of war, this time in Afghanistan alongside US allies, aiming to eliminate Taliban and Muslim extremism that threatened our security and that of the Western world.

Interestingly, at this time Bush sought and obtained cooperation from Chinese President Jiang Zemin to contain the spread of extremism from Afghanistan and the Middle East into the far west province of Xinjiang. This initiated closer relations between the US and China, described by Jiang as of the highest importance. This period of cordiality lasted for around ten years until at last Washington became concerned about Chinas growing economic might and global influence. That was a new threat to US primacy in the world.

The twenty years of War in Afghanistan did not impinge on public opinion in Australia to the extent that the Vietnam War had. There was no national conscription and only limited numbers of troops were dispatched. War rhetoric related to how Muslim extremism might be imported into Australia, not to a threat of military invasion. China, Australia and the US all viewed the War in Afghanistan as a matter of grave concern but unlikely to spread to their homelands. As long as the war lasted, they concentrated on building strong economic relationships to the benefit of all sides.

How could it have happened therefore that relations would deteriorate in recent years to the level where Australian ministers spoke of the threat of Chinese military invasion? Times of peace and cooperation were surely desired by all, yet undoubtedly there was a campaign to create fear and loathing and create an atmosphere where conflict might be a real option. The answer to this question is easy to find, and perhaps Tolstoy has expressed it best In all history there is no war that was not hatched by the governments, the governments alone, independent of the interests of the people, to whom war is always pernicious even when successful.

What is different between 1972 and 2022? It is this: that a large part of the world has forgotten the overriding importance of peace and international cooperation. It was this common longing that inspired the formation of the United Nations in 1945. It seems that following a prolonged period of peace, broken only by limited localised wars, the world has forgotten the benefits of multilateral cooperation. The focus on bilateral relations is dangerous. It risks sliding into a new and dangerous, possibly nuclear, arms race and war.

The Kremlin has denied that there will be any truce in Ukraine to mark Christmas, which should be a season of peace and goodwill. The noise of war and conflict is intensifying. It is in this environment that the older generation, whose childhood memories were shaped in the horrible years of global warfare, must find a way to communicate their concerns to the young. In the words of Pope Francis, “Great social challenges and peace processes necessarily call for dialogue between the keepers of memory the elderly and those who move history forward the young.”

Although, in 2022, disrespect for the role of the UN Security Council and General Assembly has complicated the Russian/Ukraine conflict, with all its faults, the UN still offers the best prospect of preventing or stopping war. As Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has tweeted, A majority of UN member countries now acknowledge that the Security Council should be reformed to reflect todays geopolitical realities. I hope regional groups and countries can work together to achieve greater consensus on the way forward and the modalities of reform. It is an urgent task, but one that might, just might, bring peace on earth.