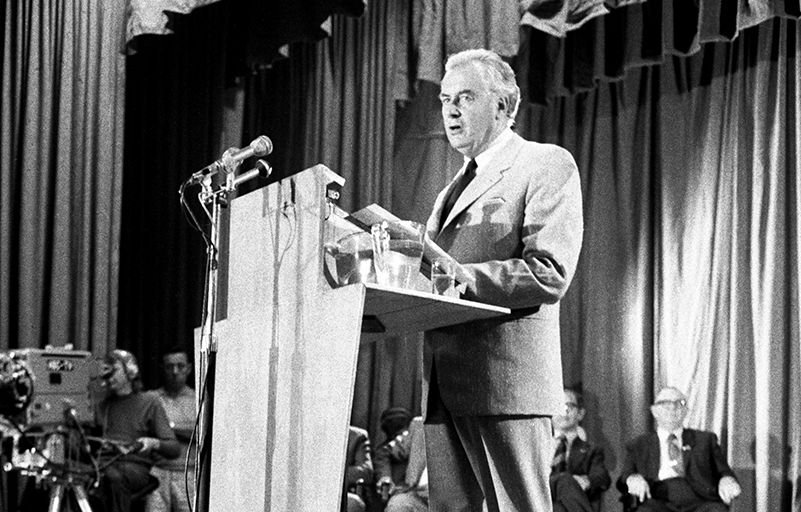

Whitlam was elected fifty years ago today: Medibank/Medicare was conceived five years before that

December 1, 2022

_On a bleak Melbourne midwinter night in 1967, Medicare was conceived. The election of the Whitlam Government on December 2 ,1972 gave impetus to what was to come. Medicare was finally launched in 1975.

_

It was hard-going developing policies in Opposition, particularly for a reform party out of power during the long Menzies ascendancy.

Health policy was no exception, but a turning point came on the night of 6 June 1967, at the home of the late Dr Moss Cass in Melbourne. Cass was among the most farsighted and perceptive thinkers on health policy that I had met.

As Gough Whitlams ‘Chief of Staff’ in an office of only three people in the mid-1960s, I had been building up groups of people who could advise him on a range of issues, such as education, science, housing, transport and health. These groups were the building blocks that Whitlam used to rewrite almost the whole of the ALP platform. He called it ‘Labor’s New Testament’.

The groups were made up of professionals, academics and other reform-minded people who freely gave their skill and time. Few were members of the ALP.

Professor Sol Encel was my chief collaborator in building these groups. He was Reader in Political Science at the Australian National University at the time. Encel suggested Cass as an adviser on health policy. Cass had written an influential Fabian Society pamphlet on health policy and advocated a national health system founded on public hospitals and health centres staffed by salaried doctors.

In 1967, the ALPs election prospects seemed as bleak as the midwinter night when Whitlam and I rang Casss front door bell. Many years later, Whitlam asked me what time of the year the meeting was held. I recalled it was midwinter because Cass had lit a log fire to try to cheer us up. The evening turned out to be a historic turning point, although no-one recognised it at the time. If we had realised how important it was, we would at least have had a photographer present!

Cass had also invited Dr Rod Andrew, Foundation Dean, Faculty of Medicine at Monash University, who had been a public advocate of more salaried staff in hospitals. Also present was Dr Jim Lawson, Superintendent of the Footscray Hospital, who was described by Cass as having a view that there were too many hospital beds, and that they should be used more efficiently and with greater emphasis on care in the community. Dr Harry Jenkins, the ALP spokesman on health in the Victorian State Parliament, was also present. However, the key attendees. were two young researchers from the Institute of Applied Economic Research at Melbourne University, John Deeble and Dick Scotton. Deeble had previously been Deputy General Manager of the Peter MacCallum Clinic in Melbourne. Scotton had been economist at the Commercial Banking Company in Sydney and doing research at Melbourne University on the pharmaceutical industry, hospital costs and compulsory and voluntary health insurance.

A scheme of universal health insurance

From that 6 June 1967 meeting, Deeble and Scotton developed a universal and compulsory health insurance scheme for Whitlam to be funded by a tax levy.

In May 1968, Deeble and Scotton distributed their paper, A scheme of universal insurance (unpublished paper, Institute of Applied Economic Research, May 1968). Whitlam used this academic treatise as a major input in his own policy development. In July that year, 13 months after the meeting at Casss house and almost five years before he became Prime Minister, Whitlam outlined The alternative national health program (called Medibank, and later Medicare), which was to become so much part of Australian national life.

Voluntary versus compulsory health insurance

Whitlam had been persistently criticising the shortcomings of voluntary health insurance. He had asked many questions on notice in Federal Parliament since the early 1960s about the high cost, high reserves and limited coverage of private health funds. We were of the view that, on a per capita basis, the total cost of the Australian health system exceeded by a large margin the cost of the NHS in the United Kingdom, but we were finding it hard to prove. We could identify the Governments health costs, but the additional costs to individuals, either directly or through their health funds, were hard to pin down. We suspected that the higher costs in Australia were due to the inefficiencies of the health funds and the perverse financial incentives inherent in fee-for-service, which encouraged over servicing and overprescribing.

So when Whitlam met Deeble and Scotton to discuss their new approach to health insurance, he was very receptive. They explained that a compulsory and universal scheme would be cheaper than existing arrangements. There was thus the exciting prospect ahead of a health scheme that was both universal and also politically defensible as to cost.

The campaign against Medicare/ Medibank

The long drawn out battle for the Medibank reforms was unrelenting in both the 1969 and the 1972 elections. John Cade, General Manager of the Medical Benefits Funds of Australia, said in August 1968, that Karl Marxs theories have never been wanted by Australians. The Australian Medical Association (AMA) and the more militant General Practitioners Society in Australia supported the shrill and long campaign against Medicare/Medibank.

The two Medibank Bills were three times rejected by the Senate after the 1972 election and were only finally passed after a double dissolution of Federal Parliament and the joint sitting of Parliament in July 1974. The Medibank Bills were two of the six Bills on which a double dissolution had been secured in April 1974. But, even then, the Coalition Opposition, supported by doctors, would not concede. The implementation of Medibank was delayed further by the Senate in late 1974 when it rejected three Bills to impose a 1.35% levy on taxable incomes. As a result it was decided to finance the scheme initially from general revenue, and the funding was provided in Bill Haydens first Budget in August 1975.

At that time I was Secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. It had been an eight year struggle from 1967.

It was worth the effort.