IAN MACPHEE. Manus Island

September 29, 2019

As a defence lawyer in criminal cases in New South Wales and Papua New Guinea I saw many prisons, including on Manus Island. Most had a harsh reality that one might expect in jails for convicted criminals. Yet I will never forget some of the cruelty inflicted on prisoners who had misbehaved in NSW jails.

I did not see that in PNG. Yet, successive Australian governments have inflicted outrageous mental pain on asylum seekers who have never been convicted of crimes in Australia or PNG. This has been starkly revealed in an alarming account of detention in a primitive prison created by Australia on Manus Island in PNG.

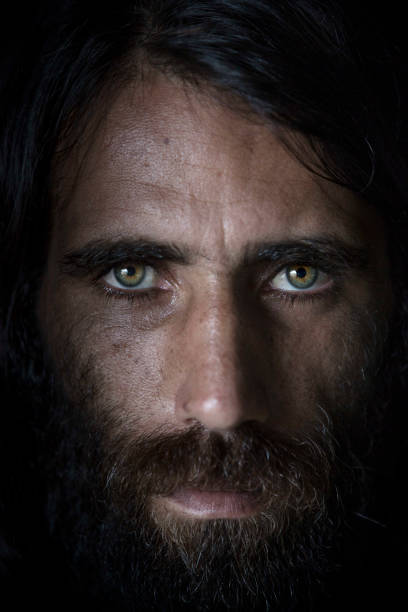

Behrouz Boochani. Photo by Jonas Gratzer/LightRocket via Getty Images.

The distressing book was written by a scholarly Kurdish poet, writer and film maker who fled Iran and sought asylum in Australia. Entitled No Friend But The Mountains, it was written by Behrouz Boochani who used a concealed mobile phone to text daily extracts to his translator, Omid Tofighian, who has a PhD from Leiden University, an honours degree in philosophy from Sydney University and is an Honorary Research Associate for the Department of Philosophy there. His translation is superb and the book could not have been published otherwise. It was published by Picador in 2018.

The author first won praise as a young Kurdish poet. He has degrees in political science and geopolitics from two universities in Tehran. From his jail cell on Manus he has written for major Australian newspapers. He would be a marvellous Australian.

As an Immigration Minister who worked with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) and Malaysia, New Zealand, Canada and the USA, I have been outraged by the inhumane treatment of asylum seekers from the Howard government onwards. Prisons behind barb wire in Australian deserts soon extended to the Australian Christmas Island, the tiny Pacific island nation of Nauru and PNG’s Manus Island. This book reveals the abominable treatment of people mostly fleeing persecution in prisons administered by a private company! What values allow Australia to invite a company to make profits out of increased suffering of people fleeing tyranny and applying for assessment in accordance with International Conventions that Australia has undertaken to comply with?

One can only imagine how one of our most distinguished human rights lawyers, Gillian Triggs, feels in her new role as Assistant High Commissioner for Protection in the UNHCR. I do know how another distinguished Australian human rights lawyer, Julian Burnside, feels. We are both despairing at the inhumanity of most of our politicians from the Howard government onwards. And so would most Australians be if they read this book.

Another distinguished Australian, Richard Flanagan, wrote the splendid Foreword for the book and I hope that some of the quotes from it will inspire many readers of Pearls and Irritations to access the book. Flanagan accurately describes the crisis:

Everything has been done by our government to dehumanise asylum seekers. The very existence of this book is a miracle of courage and creative tenacity. It was written not on paper or a computer but thumbed on a phone and smuggled out of Manus Island in the form of thousands of text messages.

Movingly, Flanagan adds that we should recognise ’the difficulty of its creation, the near impossibility of its existence’. He adds: ‘Our government jailed his body but his soul remained that of a free man’. The lives of those imprisoned on Manus ‘are stripped of meaning. They were imprisoned without charge, without conviction and without sentence’.

Hence, some have brutally cut or burnt their bodies or sewn their lips together. I agree completely with Flanagan’s judgement:

with only the truth on his side and a phone in his hand, one imprisoned refugee alerted the world to Australia’s great crime… Reading this book is difficult for any Australian. We pride ourselves on decency, kindness, generosity and a fair go. None of these qualities is evident in Boochani’s account of hunger, squalor, beatings, suicide and murder.

Yes, the story is horrific yet the writing is inspiring and the translation marvellous. Omid Tofighian has continued to help Boochani transmit information around the world. When his work was presented at UNSW in 2017 he engaged with participants through WhatsApp.

As Boochani has argued, if Australians were allowed to know of the qualities of the people who had fled persecution they would appreciate the contribution they could make to Australia and its evolving culture. If only the character and skills of refugees could be understood most Australians would oppose harsh government policies.

The contrast with the assessment and settlement policies of the Fraser, Hawke and Keating governments could not be greater. That policy was bipartisan. We worked together to explain our policies to the public. From Howard onwards the major parties have pandered to paranoia.

SYDNEY, 27 Aug 2016 Protesters hold signs at a rally to demand all asylum seekers and refugees be brought to Australia following PNG government’s decision to close the refugee camp. Photo by Hugh Peterswald. Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images.

SYDNEY, 27 Aug 2016 Protesters hold signs at a rally to demand all asylum seekers and refugees be brought to Australia following PNG government’s decision to close the refugee camp. Photo by Hugh Peterswald. Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images.

Racism has returned and has been increased by an ill informed fear that most Islamic people are terrorists and that those who are not will never integrate into Australia. That is not true. Thousands have done so when local communities have tried to understand them. There are many parts of Australia where they have been welcomed and have made a contribution to a broadening of knowledge and opinion. If we tried to understand Kurds like Boochani they could be as successful in integration as were the Vietnamese.

One of the tragedies of The Treaty of Versailles after World War I was the creation of Iraq instead of three nations: one Kurdish, one Sunni and one Shia. The treatment of Kurds since has been why people like Boochani have fled tyrants like Saddam Hussein. Most have no choice but to flee by boat. Many are arriving by plane now but that is another issue. Boochani’s experience is typical of most asylum seekers since our government ignored working with the UNHCR and neighbours to help people fleeing tyranny. They were desperate enough to give their minimal resources to ‘smugglers’ who put them on overcrowded rickety boats to sail in wild seas to countries that they dared to hope would accept them. Australia was one of those.

Hence, Boochani arrived first in Indonesia where he and those with him met hundreds of others who had realised that they could not settle in Indonesia and were told that their only hope was Australia. Had we had a UNHCR process such people could have been settled in countries where they had relatives or people from the same region of the country they had fled. That was the process we had for settling refugees from Vietnam or Cambodia in Canada, USA, New Zealand or Australia.

Instead Boochani and many others had reached Indonesia on hazardous boats and, after a few months of trying to settle there, took more fragile, overfilled small boats to Australia. The Australian Navy rescued Boochani and fellow asylum seekers as their boat was about to sink. The Navy then took them to Christmas Island and they were soon flown to Manus Island or Nauru.

Boochani describes the shock of their arrival to ‘soulless cages’ with vast numbers of mosquitoes, unknown to Kurds, that swamped prisoners lacking nets to protect them. Malaria and encephalitis threatened lives. Near starvation harmed most of those who were in the prison. Most soon had little flesh on their bones unless they managed to often be at the front of the long and narrow queue and grab as much food as possible.

Boochani writes: ‘what reason could there possibly be for a person to have to endure extreme suffering’? Manus is ‘oppressively hot… agonisingly humid. Suffocating, especially in the shameful, cramped prison cells in a massively overcrowded prison… The prisons are a confrontation of bodies, a confrontation of human flesh’. Small rooms have beds virtually adjoining each other. Rooms are adjacent. Corridors with rooms on each side are long and so narrow that it is hard for people to pass each other.

Worse still is the fact that so many prisoners are from many countries with different cultures and languages. It is, therefore, hard for them to converse and settle in a civilised manner. As they arrived they were forced into rooms regardless of any cultural links. Asylum seekers include some from Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Iran, Iraq (including Kurds), Lebanon, Somalia, Pakistan and Rohingya from Myanmar. The one thing they shared was an endless supply of cigarettes. Food was scarce but cigarettes not. Toilets are few and rarely cleaned. When allowed to walk in the small area outside the prison many urinate.

After a few months the rooms were rearranged for people of similar culture to be together. This should have happened at the outset. Before it happened, isolation compounded stress that all had endured when fleeing their country and struggling on fragile, overcrowded vessels in wild oceans. As Boochani observes: ‘we are a bunch of ordinary humans locked up simply for seeking refuge’. And desperate people of sometimes conflicting cultures find that their stress worsens because of their forced interaction without communication skill. This was especially the case in their first three months.

At page 125 Boochani writes:

In addition to the torment produced by the oppressive enclosure of the prison fences, every prisoner creates a smaller emotional jail within themselves something that occurs at the apex of hopelessness and disenfranchisement. Most prisoners evaluate their health and vitality through regular close examination of their bodies, developing fragmented and disrupted identities and a sense of self that makes them more cynical of everyone else.

That seems to be the purpose of the prison: ’to drive prisoners to extreme distrust so that they become lonelier and more isolated’. It is no wonder that many try to suicide by knife or fire.

Adjoining the prison containing the men are others containing women and children. There are sparse areas for them to walk in and as the sun shines on the metal roofs and wire fences the heat intensifies. Being surrounded by jungle the evening brings a welcome silence. Yet it is still hot and stuffy and a vast contrast with the cold mountains of Kurdistan. Other reports have revealed the suffering of children.

Mercifully, in the prison Boochani was in, there was also an Iranian singer and comedian who entertained prisoners in a crowded corridor most nights. That was the only relief that one of the four adjacent prisons had on Manus. For it is clear from Boochani’s account that guards were cold and sometimes harsh in their treatment of prisoners. I can’t imagine that Australian police or military guards would be as cruel to asylum seekers as are those employed by companies making profits from detention. Guards even forced prisoners not to play games like backgammon. It seems that many of the guards were ex-servicemen who had served in Iraq and Afghanistan where they were ordered to kill people.

In April 2016 the Supreme Court of Papua New Guinea declared that the Manus Island detention centre was illegal because none of the prisoners had committed an offence in PNG. Yet it was not until October 2017 that the centre was closed. The hundreds detained were then moved to ‘accommodation facilities’ on Manus Island. This year some have been sent to Port Moresby. It is unclear at present how they have been settled there and at whose expense. I cannot imagine that many would be permanently settled there so a serious problem remains. And it is Australia’s responsibly not Papua New Guinea’s.

I wrote in an earlier article in Pearls and Irritations that I despise the way some of our politicians (including our Prime Minister) parade their Christianity but betray its fundamental principle: do unto others what you would them do unto you. The sheer inhumanity of policies since 1996 have made me ashamed to be Australian.

Ian Macphee was Minister for Immigration in the Fraser Government