IAN McAULEY. Reclaiming the ideas of economics: Socialism

November 27, 2019

Its unfortunate that the term socialism has become a weapon in the armoury of those who stop government from performing its economically-justified functions.

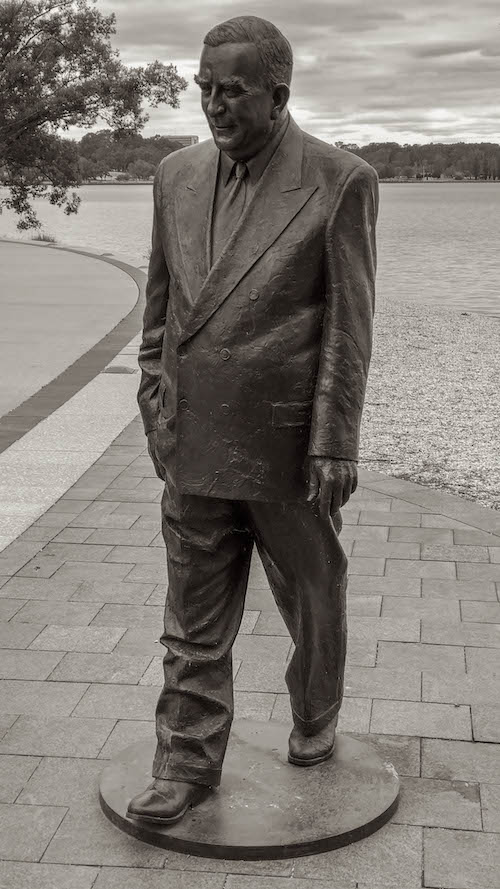

In 1944, on the foundation of the Liberal Party, Robert Menzies spelled out the partys core principles:

a true revival of liberal thought which will work for social justice and security, for national power and national progress, and for the full development of the individual citizen, though not through the dull and deadening process of socialism.

The Liberal Party has quietly dropped ideas of social justice and national progress, and has re-defined security in authoritarian terms, but it still holds on to its rejection of socialism. In the lead-up to the 2019 election, Dan Tehan, commenting on Labors child care policy, said that it was a fast track to a socialist, if not communist economy. Whenever Labor promises to strengthen or expand Medicare, there are inevitably voices accusing it of advocating socialised medicine. In the current political contests in the USA and the UK the word socialist is used to discredit the economically-responsible platforms of candidates such as Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn.

The word socialism lacks hard meaning however, there being as many definitions as there are languages and dictionaries. At one end of the spectrum of meanings it is a brand name for social-democratic parties, such as Spains ruling Socialist Workers Party. At the other end of the spectrum it means collective ownership of all means of production the meaning that allowed communist governments to use the term socialist in the names of their rgimes. Like the word aspiration it is a term into which one can assign a wide field of meanings a floating signifier but its association with authoritarian communism has allowed it to take on a pejorative meaning.

Parties of the political right, or private lobbies defending rent seeking, can taint any proposal to expand the scope of government with the term socialist. And even the right is not immune from having this usage turned on itself: the National Party, renowned for its pork barrelling and regional boondoggles, is often disparagingly referred to as a party of bucolic socialists. Its one of the terms designed to defend the rights small government agenda, and to attack any expansion of the reach of government, no matter how economically justified such an expansion may be.

There is a whole set of goods and services which governments provide, fund or regulate because of what is known as market failure. Some are goods and services which only governments can provide, such as national defence, country roads and weather forecasting, because there is no way companies can make a profit out of them. And there are others which the private sector can provide, but less efficiently than governments, such as health insurance, urban roads (using tolls) and policing. Abraham Lincoln summed up this role of government when he said:

The legitimate object of government is to do for a community of people whatever they need to have done, but cannot do at all, or cannot do so well for themselves, in their separate and individual capacities.

That principle is based on economic efficiency, and in terms of laying down a basic economic role of government it should be uncontentious. Republican presidents such as Eisenhower have quoted it, but importantly it has been absent from the statements of later Republican presidents, even those who (unlike the incumbent) were basically literate. In Australia Coalition governments, in the name of small government, are notorious for using expensive private mechanisms to do what the public sector could do more efficiently and equitably.

These functions to do with market failure are covered in public finance text books, and, for readers who arent too attracted to economic equations, in Miriam Lyons and my book Governomics: can we afford small government?. In this essay I want to cover another function which, if the language had not been so abused, I would call the socialist role of government. Its about things we choose to share.

The Harvard political philosopher John Rawls developed a theory of distributive justice based on a thought experiment: imagine that you are asked to write the rules of distribution in a society which you will occupy, but without knowing what your position in that society will be your original position to use Rawls term.

Confronted with such a thought experiment the rules we develop tend to be egalitarian. We come out in favour of social security transfers and progressive taxes.

We may believe his theory has little relevance outside a university philosophy class because we do actually live in a society and we do know our position in that society. We have a fair (if not always accurate) feel for our own employability and our own financial security, for example.

But in some areas of our life we can be in or close to an original position. We know that our fortunes could change in a flash a car accident, diagnosis with a debilitating but non-fatal condition, an unexpected need to give up work and provide care for someone close to us. These are the areas of our lives where we may be more willing to pool our chances with others, through national health or disability insurance for example.

The principle of equality of opportunity rests on the same idea of an original position. Even those who may take a hard line on distributive welfare may feel strongly that everyone should be able to set out with fair rules of life. Belief in a fair go does not necessarily translate to a belief in a fair outcome.

The key point of Rawls work is that he was not some romantic idealist espousing a utopian vision of a society with equality of outcomes. His arguments are based on the traditional economic starting point of self-interest. (He was, after all, a loyal American.) Perhaps in most realms of our lives we may be willing to take our chances as imagined rugged self-reliant individualists. But not in all realms.

Labors traditional attachment to the idea of the social wage, first outlined in the 1945 White Paper on Full Employment, aligns with Rawls ideas. Its emphasis is on education, health care and pensions all areas where we may find ourselves in an original position. They owe far more to Rawls and Keynes than they do to Marx.

Even beyond the self-interest that underpins Rawls theory, we may choose sharing in certain other domains because we consider sharing to be something of value in itself. If that is socialism, why are politicians on the left so apologetic about it and why are politicians on the right so bothered by it? Its simply about an old-fashioned moral virtue we try to teach our children that there are some areas of our life where sharing is the norm.

This is the eleventh of a series of articles in Pearls and Irritations on reclaiming the ideas of economics. Others so far have been:

General introduction (September 19)

Aspiration (September 26)

Jobs and Growth (October 3)

Society, economy and the environment (October 10)

Regulation and deregulation (October 17)

Taxes (October 24)

Globalisation (October 31)

Debt and deficits (November 7)

Wealth (November 14)

Competition (November 21)

Ian McAuley is a retired lecturer in public finance at the University of Canberra and a Fellow of the Centre for Policy development.