In Myanmar, oppression, disease and stymied aid tilt the crisis towards disaster

November 17, 2021

With the crisis in Myanmar intensifying this week, Ian Mannix, in a two-part report, looks at the conflict and how aid agencies are responding.

In the cataclysm that has followed last November’s elections in Myanmar, the country faces a new humanitarian crisis forcing aid groups to call for a rethink on how donors are providing aid.

Britain has raised the prospect of another Rohingya disaster in Myanmar, as international non-government organisations call on donors to adapt to the unfolding and now prolonged humanitarian and development crisis.

Clashes erupted on November 9 between junta forces and the Arakan Army in Maungdaw Township in Rakhine State. The respected independent online publication Myanmar Now reported residents were fearful of artillery fire: The earth shook. It was heard about three to four times," said one resident.

Frontier Myanmar reported the Tatmadaw armed forces sent reinforcements into the area and locals expressed concern that fighting might break out again. Clashes reportedly continued on the next two days.

The AA and military have been observing an uneasy ceasefire since November 2020, after fighting a brutal two-year war described by Frontier Myanmar as “the most intense fighting Myanmar had seen in decades”.

The UN Security Council (UNSC) met on November 8 to discuss the military crisis unfolding elsewhere in the country. The meeting coincided with the first anniversary of the re-election of Aung San Suu Kyi’s government, which was ousted by the military in the February 1 coup.

Britain’s deputy UN Ambassador, James Kariuki, said it was particularly concerned about the build-up of military action in the northwest of the country which mirrors the activity we saw four years ago ahead of the atrocities that were committed in Rakhine against the Rohingya".

The situation in the northwest followed an escalation of fighting between the Myanmar military and the Chinland Defence Force in Chin state and the People’s Defence Forces in Magway and Sagaing regions.

The UNSC expressed “deep concern” and called for an immediate cessation of violence to ensure safety of civilians. It made no mention of the new outbreaks of fighting but underlined the importance of steps to improve the humanitarian and health situation in Myanmar, including to facilitate the equitable, safe and unhindered delivery and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines".

It called for unhindered humanitarian access to all people in need and called for greater international support to ensure vaccine availability.

The United Nations warns that more than three million people are in need of life-saving aid due to the growing conflict and failing economy.

The UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, reported in its Myanmar Emergency Update on November 1 that there were 593,000 internal refugees in Myanmar, including more than 223,000 displaced by armed conflict and unrest since February. Most are in the southeast near Thailand.

The Border Consortium is the main provider of food and shelter in the nine camps in western Thailand and supports local partners to provide emergency assistance including health care and COVID prevention measures to displaced communities in southeastern Myanmar.

Displaced people seeking protection in Thailand as a result of conflict since the coup were only allowed to stay for a few days before being sent back to Myanmar.

The Military Junta, chaired by former General Min Aung Hlaing, continues to thumb its nose at all attempts by ASEAN and the international community to create a dialogue that might lead to a resolution of the crisis.

The population responded to the coup first with colourful and entirely peaceful protests, then with strikes by government workers in health, transport and education, under the civil disobedience movement (CDM).

Many are now resorting to open armed insurgency, guerrilla style urban warfare and targeted assassinations of coup leaders and their supporters.

There are no official figures on the death toll of civilians and soldiers although one reliable monitor says 1260 civilians have so far died.

Independent media reports on a daily basis refer to deaths of between five and 30 soldiers. Khit Thit Media counted 122 soldiers killed throughout the country on November 7.

The reports are from opponents of the military regime, so might be exaggerated, but it is clear thousands of soldiers and civilians have been killed and injured since February 1. This might make it the worst death toll of any current conflict in the world.

A key challenge facing the Tatmadaw is the Myanmar economy, which is in freefall. The Myanmar currency, the kyat, (pronounced chat) lost 60 per cent of its value in September alone. Fuel and food prices are skyrocketing while a persistent electricity bill boycott has deprived the ruling generals of US$1 billion in revenue. This means that the generals are not in a position to simply buy loyalty from the rank and file as they were in the 1990s and 2000s.

One report suggests Tatmadaw defections are likely to become a problem.

More formal and better organised opposition is being directed and coordinated by the National Unity Government, or NUG, formed by former MPs and activists who are defying the coup and providing alternative leadership.

Chillingly, a “defence ministry official” of the NUG told _Myanmar Now_that the resistance war against the junta will transform from guerrilla-style attacks into more conventional warfare in collaboration with the public.

Targeted assassinations have led to a collapse of the local government system, which in the past provided a semblance of control over health care and education, and played a role collecting fees and taxes for the government.

The public health system has all but failed, with 70 per cent of health care workers on strike to protest against the coup. Some doctors who returned to work were immediately arrested.

The public is refusing to attend military-run health services, which make up the bulk of remaining clinics and hospitals. Consequently vaccination rates remain very low. There is mounting concern in Thailand that COVID-19 will affect its population and deny the country an opportunity to open up again to tourism and trade.

As the conflict threatens to spiral out of control, the Junta is continuing its crackdown on media.

Reuters reported American journalist Danny Fenster was healthy and happy to be going home after he was freed from prison in Myanmar this week and flew to Qatar, following negotiations between former US diplomat Bill Richardson and the ruling military junta.

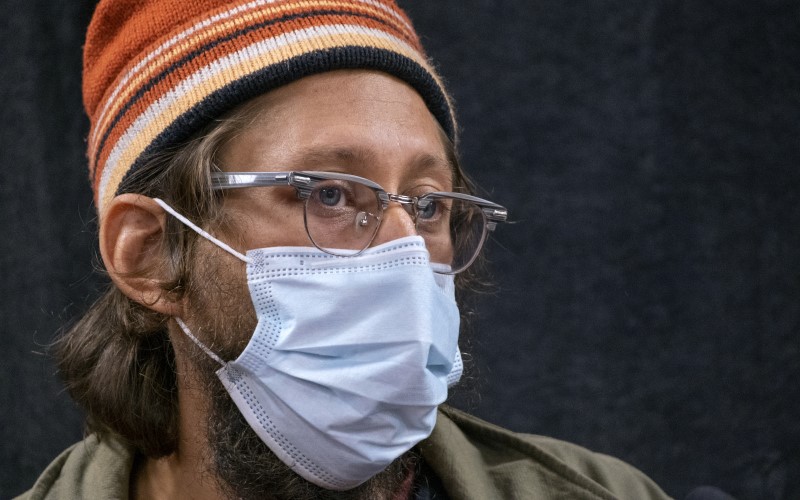

Fenster, 37, the managing editor of independent online magazine Frontier Myanmar, looked frail three days after he was sentenced to 11 years in prison for incitement and violations of laws on immigration and unlawful assembly. He had been detained since May.

Frontier Myanmar said on its Facebook page that it was deeply disappointed at the court’s decision. Its post said: “The charges were all based on the allegation that he was working for banned media outlet Myanmar Now in the aftermath of the February 1 military coup. Danny had resigned from Myanmar Now in July 2020 and joined Frontier the following month, so at the time of his arrest in May 2021 he had been working with Frontier for more than nine months.

The Alliance for Journalists’ Freedom says more than 100 media workers have been arrested since February.

The media is playing a crucial role in disseminating reliable information to the entire community through social media. The junta is powerless to stop this except when it turns the internet off completely. The country having embraced the digital economy, when this happens, money flows dry up and people cannot access banks, or place international orders.

However the net is being monitored and used as a tool for oppression.This is a new challenge for NGOs, which are seeking more flexibility and innovation from multilateral and other donors to deal with the humanitarian and development crisis.