Indonesia: going for gold

September 2, 2024

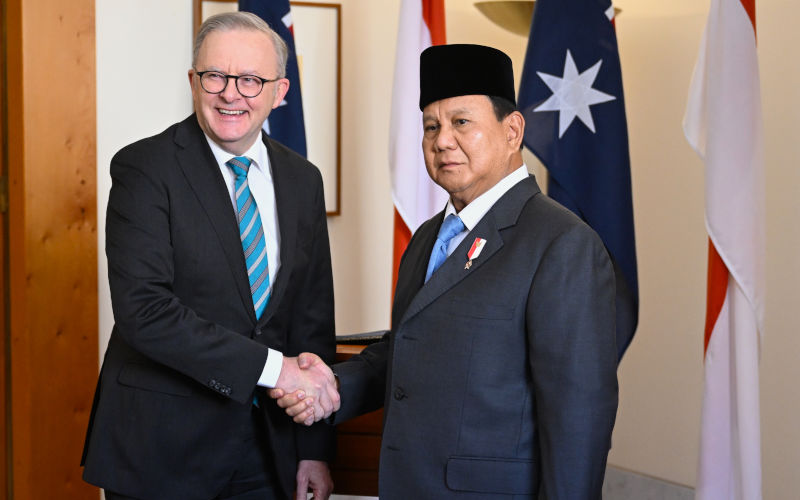

While in Canberra on 20 August, Defence Minister and President-elect Prabowo Subianto made it clear that Indonesia remains avowedly non-aligned. This stance and how Indonesia perceives the world needs to underpin our relationship.

To refresh our own sense of the country, my partner and I recently returned to Indonesia, having not been there for seven years. (We had both worked there previously.) Our hotel in Jakarta was well placed for early morning walks. How the footpaths have improved! On the first day, I noticed a huge sign, Indonesia Emas 45, or Golden Indonesia 2045: not an aspiration for the Paris Olympics, but a much larger vision. The current president, Joko Widodo (Jokowi), has set the deadline for achieving this as 2045, the centenary of Indonesian independence from Dutch colonial rule. The ambitious agenda includes accession to the OECD, becoming a high-income country and an influential, non-aligned regional power.

When I got back to Australia, people asked about our trip, which had taken us across Java, the most populated island in the world and home to 56 per cent of Indonesia’s 280 million people. They were shocked to hear that number and admitted they really didn’t know much about our closest neighbour, described in the CIA World Factbook as the world’s third-most-populous democracy and the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation.

In Java, Muslim headdress is everywhere now. The majority of women and girls — even tiny children in the hotel’s swimming pool — wear the hijab. This trend has been growing for decades. Does this symbolise a retreat from Indonesia’s moderate and tolerant version of Islam? That is the first of many questions that occurred to me during our travels. I found answers in research undertaken by Australians, Indonesians and others, mostly freely available in English on the internet. There’s no excuse for ignorance.

All along our route we were struck by the tenacity of Indonesian expressions of national pride – in the red and white flag flying everywhere and in references to “nusantara”, first coined to denote territories within the orbit of the Majapahit empire. At its peak in the 14th century, these extended from modern-day Thailand to New Guinea. That imperial connotation has faded; the word is now synonymous with the archipelago that is Indonesia. It is also the name for the new capital being built in Kalimantan.

This nationalist sentiment can have distinct regional characteristics, which makes the electoral process interesting. At the national level, the majority of Muslims and the most prominent Islamic organisations are committed to retaining a secular national government. At the regional level — the whole country returns to the polls in November to vote at the provincial, district and city levels — politics is influenced by national alliances and manoeuvring but also reflect local concerns and religiosities. They have become a battleground for Jokowi’s dynastic ambitions.

Day-to-day life seems to be even more local. Some argue that’s how the megacity of Jakarta will survive – as a series of kampungs (or villages) infused with their own sense of community. In Semarang, we walked off a main road and were soon in a food market. I asked a man unloading garlic if he’d grown it himself. No, it all came from China. Not so local after all!

China has been Indonesia’s largest trading partner for more than a decade and is among Indonesia’s top three sources of foreign investment. In 2023, China announced an investment pledge of US$21.7 billion, covering e-commerce, industry, agriculture, fisheries, science and technology. Australia’s investment stock in Indonesia is about $4.3 billion.

Also omnipresent is the mobile phone. It seems everyone has one; indeed, the statistics reveal a total of 353.3 million active mobile connections in early 2024. That’s equivalent to 126.8 percent of the total population. We had no difficulty accessing wi-fi in Java and Bali. Connectivity gets worse in more remote areas, yet internet penetration has reached 66.5 percent. No wonder people see the potential of the digital economy to help Indonesia leapfrog towards its desired high-income status.

For the time being, however, Indonesia remains a middle-income country. Fifty-two million Indonesians are now classified in the middle class. They are economically secure and have money for discretionary spending. Still, in Australian terms, monthly incomes are modest: a middle-class job pays around $500 a month. Many more Indonesians remain vulnerable to economic shocks, with up to 75 percent of jobs being in the informal, unregulated sector, mainly in agriculture, hospitality and trade. Most informal workers are poorly educated and ill-equipped to improve their lot. Nor do they readily have access to social services.

In Jakarta, prosperity manifests itself in big and small ways. The new metro system has transformed life for those who can afford to use it (a ticket costs 30 cents per station) and to live in proximity of one of its 13 stations. These middle-class Indonesians now walk, unheard of in the past, to public transport hubs. The productivity gains must be enormous, both in terms of the economy and cultural capital. And everyone visits the malls, though only the megarich can afford to buy luxury items for the eye-watering amounts imposed by the monopolistic arrangements that rule in these complexes.

To address income inequality, during the February 2024 presidential campaign all the candidates promised to increase taxes. The winner, Prabowo, vowed to raise the most, $100 billion. The wealthiest Indonesians can certainly afford to pay up. Prominent on the rich list are Indonesian Chinese, which still prompts criticism of their penchant for wealth accumulation, although anti-Chinese Indonesian feeling was more pronounced when I lived in Jakarta in the 1980s. Now the role of Chinese in the development of the nation is emerging as an important strand of Indonesian history, even in discussions about who brought Islam to the shores of Java. Was it the 15th century Chinese admiral Cheng Ho Sam whose shrine we visited at the impressive Po Kong Temple in Semarang?

A visit to another tourist attraction, in the East Javanese city of Malang, brings us back to the poor of Indonesia. Kampung Warna-Warni (Village of Colours) has been transformed, not only by a paint job, but also by the tourist dollars it attracts and a new social dynamic within the village. The change began as a university project. Students partnered with a local paint company interested in social responsibility to transform the slum. Bringing colour to the houses brought a sense of pride and new income streams.

Cleaning up rubbish is no easy task. Get off the beaten track just a few hundred metres and you are confronted by the scale of the problem. Plastic is one of the worst challenges; it takes so long to decompose and flies off open rubbish piles on the slightest breeze. Huge billboards exhort Indonesians to look after the environment, but many seem not to notice the signs, let alone all the debris on their verges.

When we got to Bali no-one checked if we’d paid the tourist tax of $15 — we had — introduced to raise revenue to help preserve the culture and nature of Bali and improve tourism services. Some of the revenue should be spent in the northern part of the island, marred by litter on the sides of roads and even the temples. Cultural practices do remain entrenched, though it seems that what the tourist industry demands is what the Balinese deliver. Seventy percent of the island’s economy is tied up in the industry. If the influx dries up, as it did during the pandemic, everyone hurts.

Australia and China are the top two source countries for tourism to Bali, but it’s the Australian flavour that is more palpable: in the coffee culture, the restaurant style, the joint wine-making operations, the surf schools, the dog rescue shelters. This prompts my last question: with the prospect of greater investment flows mentioned in Australian Government announcements, can we not look to this type of people-to-people relationship to anchor our programs of skills developments, higher education, health, even EV collaboration? It’s not the kind of engagement proposed by those who see Indonesia through the lens of the threat from China — each country’s largest trading partner — but it might prompt more Australians to look north not for the enemy but for the opportunities and allure Indonesia can offer.