It’s not a “cost-of-living crisis”; it’s a failure to tax the rich - Weekly Roundup

August 3, 2024

If the well-off paid their fair share of tax no one would be talking about a cost of living crisis; Dutton weeps as his beloved Home Affairs Department, modelled on the Soviet KGB, is dismantled; how the gambling lobby has become Australia’s equivalent to America’s National Rifle Association. Read on for the weekly roundup of links to articles, podcasts, reports and other media on current economic and political issues.

It’s not a “cost-of-living crisis”; it’s a failure to collect tax from the well-off. The latest CPI figures show the government is on track to fix the inflation problem it inherited from the Coalition. Rex’s troubles stem from a long-term failure of public policy that sees aviation in isolation rather than as part of a transport system.

Violence against women is about more complex and deeply-seated cultural issues than toxic masculinity. The ministerial reshuffle is about cleaning up the mess Coalition left for the Albanese government. Multiculturalism reviewed – we’re doing OK but there’s work to be done. The gambling lobby – our version of America’s National Rifle Association. Hillbillies standing in the way of affordable electricity.

Two threats to capitalism and they’re not from the “left”. The “west” from the perspective of a Singaporean public intellectual. On history and democracy.

Won’t you please come to Chicago

It’s not a “cost of living crisis”: it’s a deep problem in structural inequity

We keep on hearing about a “cost of living crisis”, as if we’re all doing it tough.

That’s not so. About two-thirds of Australians are coping quite well, while the other third are indeed having trouble making ends meet.

Ross Gittins puts it clearly in his post Cost-of-living crisis? Why only some of us are feeling the pinch, where he writes “some of us are doing it a lot tougher than others, and some of us are actually ahead on the deal”.

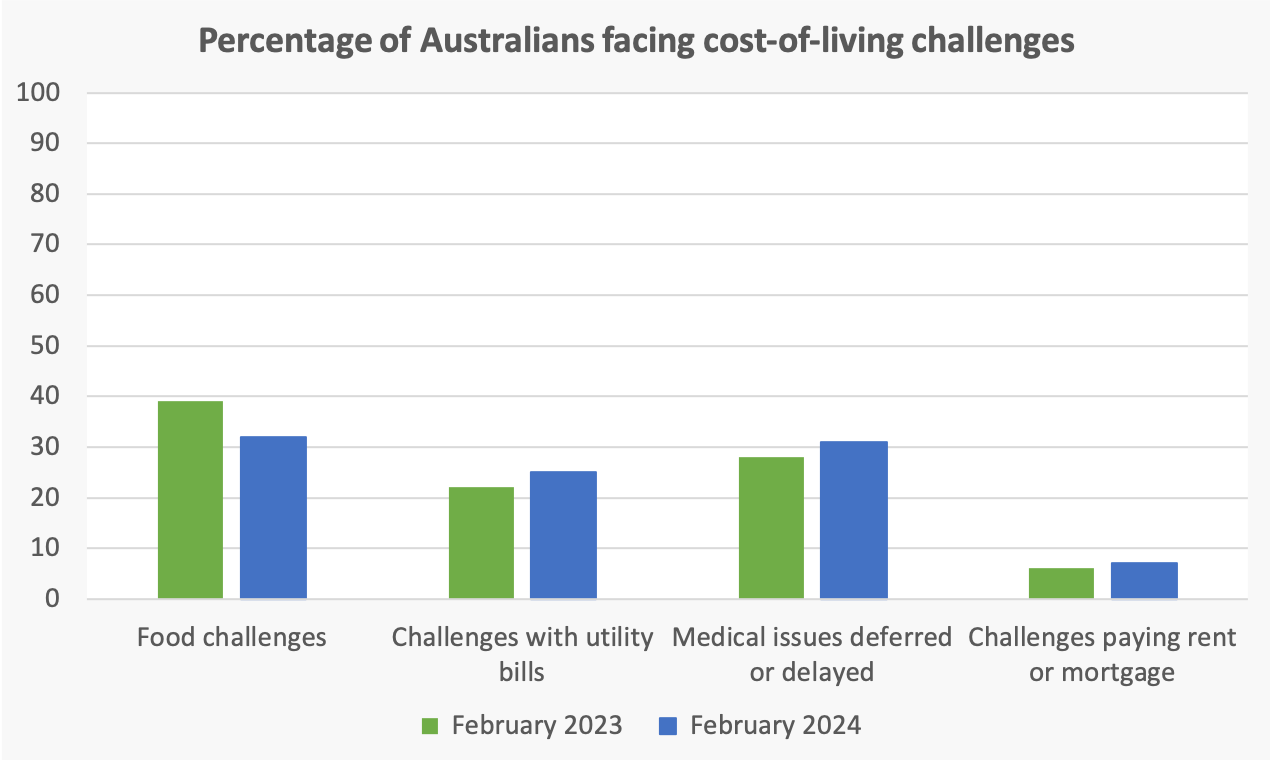

This imbalanced pattern of cost-of-living pressure is confirmed by the Melbourne Institute-Roy Morgan survey Taking the Pulse of the Nation, which looks at the proportion of Australians facing cost-of-living challenges, comparing responses in February last year with February this year.

The results covering four areas – food, utilities, health care and housing – are shown in the graph below. Notably the proportion of people experiencing food challenges is down from 39 percent to 32 percent. (This aligns with the latest ABS CPI release, which finds lowering food price inflation, apart from some items affected by adverse weather conditions.)

Other stresses have risen, reminding us that while inflation has fallen, it is still positive and for many, incomes have not kept up with inflation.

Some may be surprised that only 7 percent of people report that they are experiencing mortgage challenges, but those problems are concentrated among a small demographic group, typically younger people who have bought their first home in the last few years. Those who have given up the search for suitable accommodation and are couch-surfing or living with parents would not be facing bill stress. Therefore this figure provides a very incomplete picture of the extent of housing stress.

The ABC’s Michael Janda has a well-researched post demonstrating why most indicators tend to understate the hardship people face resulting from higher interest rates: Mortgage risks are rising but are they still understated by the RBA?. For example some people are free of mortgage stress because they have sold their properties, having borne the hardship of incurring transaction costs of buying and selling within a short period. He notes that the number of homes resold within 3 years has risen sharply since 2022.

The RBA, he says, focuses on the number of owner-occupiers who are in arrears in their mortgage payments as an indicator of mortgage stress. That indicator has been low and stable for a few years, but it doesn’t cover those who are making significant sacrifices in order to avoid going into arrears.

Even when we compensate for the understatement in that 7 percent figure, it is still clear that only a small proportion of Australians have been badly affected by high interest rates. As Gittins points out there is a sizeable proportion of the population with mortgages whose repayments have risen because of higher interest rates. But who hasn’t had the experience of juggling changing incomes and expenses? That’s not a “cost of living crisis”.

Unsurprisingly the Melbourne Institute-Roy Morgan survey finds that at least 60 percent of people facing cost-of-living challenges report symptoms of mental illness – feeling depressed or anxious “all of the time, most of the time or some of the time”. That compares with 26 percent or less among those without challenges.

The $3000 test

As an indicator of precarity the survey looks at people’s capacity to meet a requirement to come up with $3000 within a month to cover an unexpected expense. That may be emergency car or house repairs or travel because of a family tragedy. Almost all of those two-thirds without challenges have access to liquid resources, but others are far less resilient. The people most seriously short of cash are those finding it difficult to pay rent or a mortgage, suggesting their sources are close to maxed out.

The ABC’s Hanan Dervisevic draws on the Melbourne Institute-Roy Morgan survey, and data on the fall in household savings, to write about the way people can develop an emergency fund: How much should you have saved in an emergency fund? Experts say the key is to start small. Financial advisers, she points out, suggest people should have three to six months of take-home pay in such a fund.

She doesn’t go further into the benefits of people having a cash or near-cash reserve, but they can be considerable. People with such a buffer can do without credit cards and buy-now-pay-later schemes, using debit cards instead. They can take advantage of substantial discounts in house and car insurance by choosing policies with high deductibles. In general, those with liquidity have the means to free themselves from subsidising a bloated high-cost finance sector.

It’s about an unfair and enfeebled tax system

The main finding in the Taking the Pulse of the Nation report is that there is something very wrong with the distribution of wealth, income and opportunity. There has been an extraordinary failure when a third of people are reporting food challenges in a country so naturally bountiful as Australia. Similarly it is disgraceful that a third of people should be deferring or delaying medical procedures.

The easy and partisan response is to blame the Albanese government, as if these problems have arisen because of policy failures over the last two years. But the problems are more entrenched. People’s difficulties in buying food result, in part, from high-cost practices within the food industry, including excess packaging and advertising.

They also result from failures of successive governments, mainly Coalition governments, to attend to economic reform. Weak competition policy has contributed to high food prices, successive cuts to Medicare have contributed to challenges in meeting health costs, privatisation of electricity authorities and a failure to invest adequately in renewable energy have contributed to high utility costs, and severe cuts in public housing have contributed to housing stress.

The cost of these failures is concentrated unfairly on a third of Australians. Once we see it that way, rather than as a “cost-of-living crisis” that implies a shared burden, we have to face the uncomfortable fact that its solution involves spreading the cost more fairly, particularly by having the well-off pay more tax.

If the Albanese government is to shoulder some of the blame for this situation it’s for having done too little to repair the damage it inherited from the Coalition, particularly our weakened public revenue base. But the Coalition has absolutely no intention of getting the privileged to pay more tax, and politically they are very satisfied when journalists keep referring to a “cost-of-living” crisis.