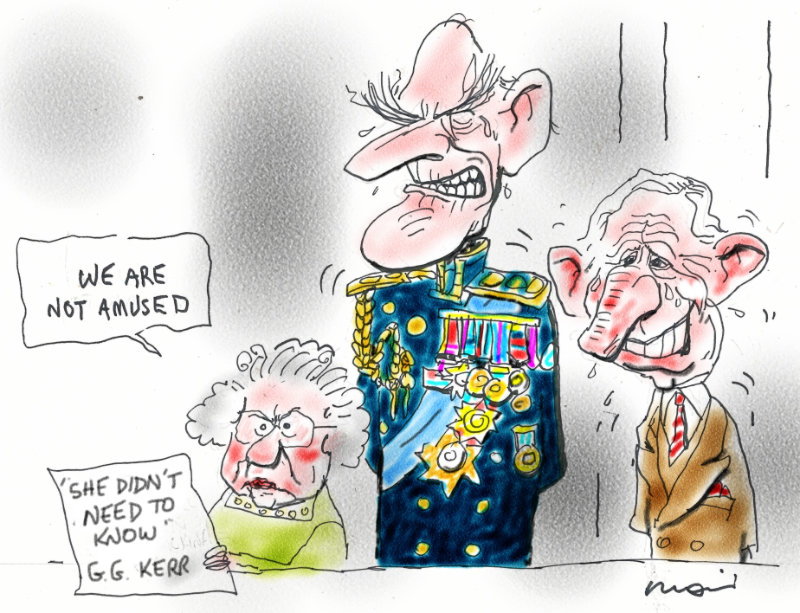

The Palace Letters have blown apart the claim the Queen had no part in the Whitlam dismissal.

July 14, 2020

_The letters show that the Queens responses, and at times even advice, particularly in relation to Kerr’s concern for his own position and the possible use of the reserve powers, played a critical role in his planning and in his eventual decision to dismiss the government.

_

In doing so the Queen breached the central tenet of a constitutional monarchy, that the Monarch is politically neutral and must play no role in political matters. The damage this has done to the Queen, to Kerr, and the monarchy is incalculable.

The Palace letters have proved to be every bit the bombshell they promised to be, and neither the Queen nor Sir John Kerr emerge unscathed.

In his vast, increasingly frequent letters and telegrams to the Queen, the governor-general provides the most extraordinary vice-regal commentary on the decisions and actions of a prime minister and elected government imaginable. They provide a remarkable window onto Kerrs views of Gough Whitlam, his planning, his options, his fears, and his eventual decision to dismiss the government.

Letter by letter, particularly from late August 1975, months before supply had even been blocked in the Senate, Kerr draws the Queen into his planning regarding the crisis unfolding in the Senate, including the possible use of the reserve powers. Kerr details options and strategies, which are then discussed with the Queen through her private secretary, Sir Martin Charteris.

These include Kerrs concern that prime minister Whitlam might recall him as governor-general, which he discussed with Prince Charles in September 1975 in a profound breach of political and constitutional practice. Charteris writes: “Prince Charles told me a good deal of his conversation with you and in particular that you had spoken of the possibility of the Prime Minister advising The Queen to terminate your Commission with the object, presumably, of replacing you with someone more amenable to his wishes. If such an approach was made you may be sure that The Queen would take most unkindly to it.”

It is a defining feature of a constitutional monarchy that the monarch**"**has to remain strictly neutral with respect to political matters", that the Queen must remain above politics at all times. Hundreds of pages challenge that claimed political disinterest, as Kerr relays conversations, meetings, and events to Buckingham Palace in the context of the most intensely political situation unfolding in Australia.

On September 30, “I had an interesting conversation yesterday with the Prime Minister about the current political and constitutional problems”; on September 20, “The Prime Minister and I had a detailed and important talk and he has told me privately that he has another tactic in mind.” What is pivotal throughout these letters is that the Queen, through her private secretary, engages with Kerr on these inherently political matters, even advising him on the powers of the Senate and, critically, the existence and potential use of the contentious and contested reserve powers to dismiss the government.

The Queen’s personal private secretary was kept well briefed about what was going on in Australia.CREDIT:GETTY IMAGES

Lets take just one example, from the first glimpse at the letters, Charteris letter to Kerr of November 4, 1975, on the reserve powers: “Those powers do exist but to use them is a heavy responsibility I think you are playing the ‘Vice-Regal’ hand with skill and wisdom. Your interest in the situation has been demonstrated, and so has your impartiality. The fact that you have the powers is recognised, but it is also clear that you will only use them in the last resort and then only for constitutional and not for political reasons.”

Charteris followed this up the next day with the clearest suggestion that the reserve powers may need to be used which, Charteris wrote, “places you in what is, perhaps, an unenviable, but is certainly a very honourable position. If you do, as you will, what the constitution dictates, you cannot possible [sic] do the Monarchy any avoidable harm. The chances are you will do it good”. He ends with a reference to the “discretion left to a governor-general”. These critical letters provided Kerr with the advice and comfort he needed to feel secure that the Palace accepted the existence and potential use of the reserve powers as he moved towards dismissing the Whitlam government.

This is just the first day of viewing these extraordinarily significant letters and there is much still to see and even more to assess. As we delve deeper into them, just as important as what is in the letters will be what isnt there the gaps, the events and people who should be but arent. Like the then High Court justice Sir Anthony Mason for instance, Kerrs secret guide and confidant whose role remained secret for 37 years. It is a remarkable thing that among the hundreds of pages of Kerrs letters to the Queen, he fails to tell her about the central role of Sir Anthony Mason in his thinking. That omission must raise questions about the completeness, if not the reliability, of what Kerr was telling the Queen.

Just days after the dismissal, Charteris wrote to the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Gordon Scholes, and insisted that, “The Queen has no part in the decisions which the Governor-General must take in accordance with the Constitution”. The Palace letters have just blown that claim apart. They show that the Queens responses, and at times even advice, particularly in relation to Kerr’s concern for his own position and the possible use of the reserve powers, played a critical role in his planning and in his eventual decision to dismiss the government. In doing so the Queen breached the central tenet of a constitutional monarchy, that the Monarch is politically neutral and must play no role in political matters. The damage this has done to the Queen, to Kerr, and the monarchy is incalculable.

Jenny Hocking is Emeritus Professor of History at Monash University and Gough Whitlam’s biographer.

This article is reproduced from the SMH of 15.7.2020 ,with the agreement of Jenny Hocking