John Kerin: Obituary from a staffer "The best policies are the best politics"

April 8, 2023

John Kerin’s contribution to the success of the Hawke-Keating government has been grievously understated and uncelebrated.

Given the economic, environmental, managerial and social change it successfully engineered, having someone who could neutralise the farm lobby was a boon to the ALP’s parliamentary machine. It contributed significantly to the material reforms of the Hawke/Keating era.

As Shadow Minister for Primary Industry from 1980 Kerin, like colleagues in a similar situation, had worked hard with a small number of advisers to devise and consult on a detailed plan for primary industry - against the chance that a Labor government should be elected.

Bob Hawke’s accession to the position of Prime Minister has been very well documented - although history is still to hear the view of the Drover’s Dog itself.

The need for a reformist Labor government to neutralise conservative rural forces was made more urgent and difficult by the fact that those right-leaning interests, after years of ineffective fumbling by the National Party, had been blessed with a competent and ambitious leadership group. It was the National Farmers Federation (NFF).

The NFF was formed in 1979 as a single national voice for Australian farmers. By 1983 the NFF was demonstrating its intention and capacity to be a strong conservative political force - at least in relation to larger scale producers and more significant agricultural industries, and at least in relation to farm policy narrowly defined.

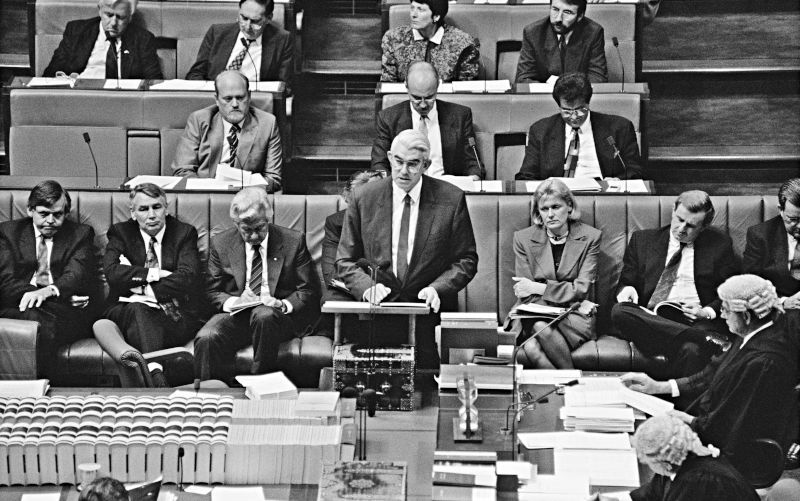

John Kerin was appointed by Hawke as his Minister for Primary Industry. He was placed front and centre in the sometimes theatrical struggle between a lively and refurbished agricultural interest group and the ambitions of a newly-formed social democratic national administration.

In 1983 some of the natural support for ‘a fair go for farmers’ occasioned by widespread drought was waning. The dry which had affected much of Eastern Australia was weakening its grip. But there were still rude clubs available with which a rural interest group might bludgeon an incoming Labor government. For one thing interest rates were ‘complainably high’ - mostly above 10% until 1995. For another there were industrial relations.

For the NFF the field of industrial relations was an obvious setting for efforts to diminish the power and place of unions. Farm leaders had already been heavily involved in the live sheep export dispute in 1978 and the NFF announced itself unsheepishly through its battle with the Australian Workers Union over the use of a wide comb (1982-83).

It was therefore no surprise when the NFF committed to a dispute involving the Australian Meat Industry Employees Union (AMIEU) at the Mudginberri abattoir in the Northern Territory. The dispute ground on from 1983 to 1986 and only ended after picket lines, 27 court cases and two years of litigation before the Arbitration Commission.

The union was fined and eventually lost face. Mudginberri was seen by the New Right as a win in the campaign to break the power of the unions and introduce contract employment. The NFF is on the public record as claiming that “the win over the Labor Government and over the unions in a bitter IR dispute just months before, galvanised the impact the bush could have when it stood united in demand of a fair go”. It seemed to be bracing itself for the role of standard bearer for those interests wanting to break the power of unions.

This could have become the main agenda in agriculture under a new Labor Government: testy battles between farmers (as employers and business managers) and unions which were of significance in the sector. The unions might have been given support for naive ideological reasons by a new Labor Minister for Agriculture.

But part of the magic of John Kerin now sadly passed from view was that he was not an ideologue and he was not nave.

Kerin was trained as an economist but was by nature a scientist. He sought evidence of what was true and without that, doubted everything. Sadly he sometimes doubted himself.

He had an insatiable appetite for facts at all levels, from the cellular to the philosophical. He read widely. He was driven by what he saw as the opportunity for a Labor Government to make Australia a more modern, productive and fairer contributor to a peaceful world. (He had lofty ambitions.)

The political situation Kerin faced was one in which:

" Labor for the most part had no profile and no following in the bush. We were up against a profound agricultural fundamentalism, constrained by a federal structure which allowed the parties to play off one set of interests against another and there was indifference at best to this set of issues in the Labor Party itself ."

At the beginning of Kerin’s long term as Minister the NFF continued to circle, armed with higher expectations from its more militaristic members and growing confidence in its own power. It set about fomenting the 1980s version of ‘A Rural Crisis’.

On 1 July 1985 an estimated 40,000- 45,000 farmers and their friends rallied at Parliament House “to protest about the effect of taxes and charges on the farming community and lack of government concern about their welfare”. In December of the same year 25 tonnes of Frank Daniel’s wheat was dumped at the door of Parliament House.

But Kerin was not for turning. Given his natural instincts, his fascination with the industries in his protection, and a real belief in the rectitude of the task given him, Kerin was building bridges, not moats. He opened the path between agricultural people (not just their leaders) and the evil of ‘Canberra’.

From the beginning Kerin demonstrated a technical understanding of agriculture and other resource industries but he always wanted to know more. He was consistent and approachable. And it was difficult not to like him, despite his jokes. He had what he called “a tough farming background” so his empathy with farmers and their families was deeply rooted.

As Minister he developed a vast network of contacts. He built an encyclopaedic knowledge of individuals in agriculture, fisheries and forestry and their resource, processing and financial off-shoots.

A meeting with Minister Kerin, home or away, could be charming, memorable and touching, even if one wanted to complain about reduced fishing quotas or the price of superphosphate. It certainly would never be a meeting characterised by arrogance, disinterest or interpersonal rudeness on the Minister’s part. He wanted to learn, so he listened.

The farming public, as well as agricultural scientists, researchers and public servants, grew quickly to trust Kerin and soon thereafter to like working with him. More rabid right wing commentators could agree that he was a good man in the wrong political party.

Meanwhile, over at the NFF, Ian McLachlan was playing a straight bat as President (1984-1988) as a warm-up to becoming Minister for Defence in a Howard Ministry (1996). He was followed in the Chair by John Allwright (1988-1991) and Graham Blight (1991-1994). The relationship between Presidents and Minister were cordial, respectful and businesslike.

For political effectiveness the NFF looked to the drive and leadership of Executive Directors, Andrew Robb (1985-1988) and the tragically parted Rick Farley (1988-1995). The organisation was well cashed-up for action: farmers had contributed millions of dollars to establish the Australian Farmers Fighting Fund.

Even with these assets at their disposal, nothing could prevent the NFF from respecting the Minister.

There was to be no refusing Kerin’s personality and working style. In his own policy memoir (of 720 pages) he listed the reform issues he took on:

“- they were about structural adjustment; gaining commodity production efficiencies; productivity increases; gaining some stability in essential research funding; establishing more relevant infrastructure and institutions; ensuring essential awareness of environmental issues; the elimination of self-defeating subsidies and protection; defining and implementing rural policies, not just agricultural; and about the government’s work to achieve international agricultural trade reforms.”

In July 1987 Kerin was appointed Minister for Primary Industries and Energy. This covered agriculture, fisheries, forests, and minerals. It was an enormous load of subject matter, much of it extremely complex and requiring detailed consideration. The industries in this mega-department earned about 60 per cent of Australia’s total export income.

Kerin’s success was not due just to his personality. He worked extremely hard. He often started shortly after 5.00am and worked until midnight. And most Monday evenings would see him travelling to ALP Branch meetings in his electorate in South-West Sydney.

He had the active support of the Prime Minister on many matters. The Prime Minister’s considerations were guided by the economic importance of primary industries and energy, and by the fact that he and his Minister both had the perspective of rural, regional and remote areas as home to many families and commercial activities apart from agriculture.

John Kerin’s professional journey took him from what he was delighted to describe as ‘Chook Farmer to Treasurer’. On the way he passed through philosophy and economics degrees at the University of New England and the ANU, and through the Bureau of Agricultural Economics (BAE). En route he made lifelong friendships with other economists of weight and significance, including Bob Whan, Stuart Harris and Geoff Miller. He had the constant support of his partner, June.

John Kerin’s track record in policy relating to primary industries and resource management has not been matched by any other Minister - and may never be.

His professional style, hard work and personal decency resulted, without doubt, in a positive ‘gross operating surplus’ for agriculture and other resource-based industries.

A State Funeral for John Kerin is to be held on Friday 14 April.

For more on this topic, P&I recommends:

The way I saw it; the way it was; the making of national agricultural and natural resource management policy, John C Kerin, published by the Analysis and Policy Observatory, 2017.