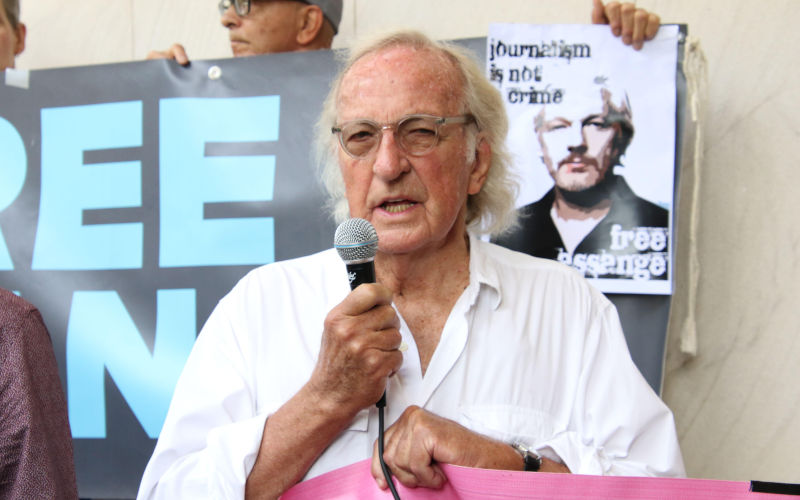

John Pilger, maverick journalist (1939-2023)

January 10, 2024

In a speech he made in Sydney in 2011, defending Julian Assange, John Pilger recalled how it was always impressed upon him when he was young that Australia was a brave country: that we stood up to authority, and we stood up for justice. Such national myths were at best half-truths, Pilger said, but in our political life, there was scant evidence of this. But now and then, an Australian came along who made such myths seem true. Julian Assange was such an Australian, he said.

I find him an extraordinarily brave Australian. And I can’t say that about many of my compatriots in the same way. I’m not saying that there aren’t brave Australians, but I can’t think of any that has really been so unusually brave by his standing up to a superpower. Brave in starting a project like WikiLeaks that he knew would get him into trouble.

One of the things that of course almost has never come out of the generally appalling media coverage of Julian and WikiLeaks is the reason for WikiLeaks. It had a moral base. It was about justice. He nailed his colours and the colours of WikiLeaks to that mast. This was going to be about justice. It was about seeking justice through letting people know what is going on, to letting people know what those who have power over their lives are saying, I can’t tell you how brave this is. Many people have tried to do this and failed. Julian succeeded actually, because the information that he has got out to people all over the world has made a difference.

Those same moral qualities that Pilger admired in Julian Assange underpinned Pilgers own journalism. Like many Australians, I have read numerous Pilger articles, a few of his books, and watched several of his more than sixty documentaries. I stand in awe of his enormous output over six decades of what he called maverick journalism.

Most of his documentaries and scores of his articles are available on his website, johnpilger.com, which is an enormous journalistic treasure trove, a contrarian archive of the history of our times.

The breadth of Pilgers journalism was staggering. Over five decades. he covered wars and social conflicts in Vietnam, Cambodia, Nicaragua, Iraq, Burma, China, Okinawa, the Chagos Islands, Timor Leste, Chile, South Africa, Australia (frequently), Mexico, Japan, Czechoslovakia, the UK, the US etc, etc. He produced powerful documentaries about these issues. He was truly a globe-spanning journalist.

His first documentary, The Quiet Mutiny, (1970) was about U.S. soldiers in Vietnam who were fragging, their officers, which was slang for throwing grenades into the tents of the commanding officers they didn’t like. Many of the conscripted US soldiers were rebelling against the Vietnam war. His most impactful documentaries were Year Zero: The quiet death of Cambodia (1979) about the Khmer Rouge and Death of a Nation: The Timor Conspiracy (1994). His final documentaries were The Coming War with China (2016) and The Dirty War on the NHS (2019).

It is worthwhile visiting his website, not only for these documentaries, but for a series of interviews he did of other journalists, called Outsiders. Pilger interviewed two other great war journalists from the generation before him who covered the Second World War: Wilfred Burchett, who talked about being the first western reporter into Hiroshima after the atom-bombing, who wrote a powerful piece of journalism, The Atomic Plague: I write this as a warning to the world, and Martha Gellhorn, who described walking into the Dachau death camp at the end of the Second World War and documenting the horrors she saw; two revelatory and astonishing pieces of journalism.

As Chomsky and Herman argue in Manufacturing Consent, the mainstream media rarely give you the truth. Instead, they give you what powerful people want you to believe. As a rare truth teller in the mainstream media, like Wilfred Burchett before him, and the man he saw as his successor, Julian Assange, Pilger presented Australians with a powerful counter-narratives to the war-mongering of our mainstream media and the ASPI-inspired propagandists of the ABC.

Since Pilger was an important supporter of Julian Assange, and had spent his last decade defending Assange, I interviewed Julian Assange’s father, John Shipton for Bay FM about his memories of his good friend John Pilger.

The two met when Julian Assange sought asylum at the Ecuadorian embassy. Assange used to host Christmas dinner there and John Shipton would go over to England every Christmas and stay ten days. He first met John Pilger when they shared Christmas dinners with Assange at the Ecuadorian embassy.

Like many Australians, John Shipton had followed Pilger - the written works more than the film documentaries. In particular, The Secret Country had a big effect on his understanding of Australia. Recently he rewatched Pilgers documentary on Palestine, which he thought held up well.

Pilgers earliest documentaries had David Munro as director and the pair had a long-term partnership which ended when Munro died in 1999 after making twenty documentaries with Pilger. Pilger wrote the scripts, was the interviewer, and the narrator. His scripts were exemplars of modern journalism, adorned with an abundance of the most viscous irony and a passionate desire to expose the deceits of the mainstream narrative. As the front man, Pilger was handsome and his camera voice, though occasionally over-preachy, was magnificent even then, sounding like Moses descended from the mountain to chastise the worshippers of the Golden Calf.

He was a chronicler of the world of the late-20th century, said John Shipton, who praised his bravery. He chronicled it all, and he feared nothing. In particular, he had the amazing capacity to maintain virtue and moral integrity, and extraordinary energy in chronicling the depravities of empire. You know, in the sense that he bore the unbearable weight of all this depravity, he managed to hold his head high and work his way through it and bring to us a truthful description of the actions of these depraved people that rule this empire.

He reported on everything: the vigour of the man was extraordinary; he was immensely productive. Having been on the road now for 11 years myself, you know, you get frazzled, and I mean that psychically, not physically. It did wear John out physically. In the last five years he had a series of sicknesses.

I don’t know the origins of his relationship with Julian, but he was publicly and privately a defender of Julian. What I mean by privately is that he introduced lawyers who he thought were competent.

John and Julian, their virtues seem to me to be an absolute hunger to seek justice, to believe that justice can come as a result of truthfulness. They didn’t say that to me. However, that is what I continued to observe. John had a greatness of soul you know; a magnificent human being in every and all respects: interpersonally, truthfully; a capacity to write, a capacity to speak, a capacity to absorb facts and information and bring it forth into a justice-seeking narrative. You know, there’s certain greatness of soul you require. He was an Australian Dostoyevsky, distinctly Australian, but he wrote in a Dostoyevskian tone.

An interesting example of mainstream media invention of facts was the claim made in one of Pilgers UK obituary that Pilger had lost money when Julian Assange broke bail and went into the Ecuadorian embassy. The same false claim can be found in Wikipedias article about Pilger. It must be true, of course, because it has a footnote that references a UK tabloid!

This wasn’t true, John Shipton contradicted. Not only was the story not true, but the tabloid misinformation also covered up an astonishing act of bias by the English judiciary. John Pilger had indeed volunteered to post bail for Assange, but the judge refused to allow Pilger to post bail, calling Assange and Pilger peripatetic Australians.

Pilger described this incident too.

My own high point was when a judge in the Royal Courts of Justice leaned across his bench and growled at me: ‘You are just a peripatetic Australian like Assange.’ My name was on a list of volunteers to stand bail for Julian, and this judge spotted me as the one who had reported his role in the notorious case of the expelled Chagos Islanders. Unintentionally, he delivered me a compliment.

Said John Shipton, I argued with John Pilger about that matter that the establishment in the United Kingdom holds Australians in contempt for our origins; that we were populated by what were called convicts. They were actually slaves. They regard us a relic of empire.

Julian Assange, who has suffered a life-endangering overdose of British justice, will find out whether he will be extradited to their US overlords on February 22. There will be protests around Australia, so find out when your local demonstration will be.

John Shipton is organising a seminar in Melbourne on Saturday March 9 at Storey Hall, RMIT called Nightfalls in the Evening Lands: The Assange Epic. John Pilger was to be one of the speakers, but the list of speakers remains impressive. The website is nightfalls.info. All the information is there.