An understated and yet a most influential and famous Australian.

June 11, 2020

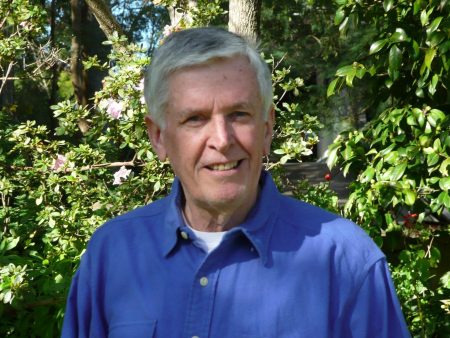

Rupert Murdoch aside, which Australian has had the greatest impact on US political and public thinking in recent decades? He comes from Adelaide, is unfailingly modest, was once in the news all the time, despises most politicians and has both incensed and stimulated people with his work.

He dislikes the limelight. He has been the subject of earnest seminars featuring prominent US academics and has been feted in Europe. But he was not on Scott Morrisons guest line-up at the White House jamboree last year.

His name is Patrick Bruce Oliphant, better known as just Oliphant, the cartoonist with the big black blob above i in his signature and his alter ego bird offering a comment from the sidelines.

For decades, Washington officialdom along with millions of other American newspaper readers woke up each day to his view of current events. Thoughts were stirred, views questioned, consciences pricked. Oliphant became the most famous cartoonist of his time. He is also an accomplished painter and sculptor.

In his heyday, Oliphants works were syndicated to 500 different publications, making him as much a household name as the great newspaper columnists of the day. One of them, Maureen Dowd, of the _New York Times,_said he could determine the fate of a politician with a few strokes of his brush. Pat is a giant, she said, and you only produce giants once in a generation if youre lucky.

P.J. ORourke, the US conservative political satirist and long-time friend, says Oliphant has a uniquely sensitive perception of evil, malfeasance and greed. He is able to see things we cant see.

Oliphant moved from Australia to the US in 1964. His work has observed all the presidents and the political decisions going back to Lyndon Johnson.

But he discovered that politics is the most boring thing you could possibly engage in, as he told Atlantic magazinein 2014. The study of the charlatans that practise it is what is enjoyable. The machinations of politics is not what is fascinating to me. It is the crookedness of the people. Politicians are disgusting people, with some exceptions.

Now 84, Oliphant set out to be a journalist but ended up even more prominent with the power of his brush and penetrating insights into the political intrigues and minds of Washington at work. In 1990, the _New York Times_described him as the most influential editorial cartoonist now working. His work and its style became the benchmark for other cartoonists.

He began at the _Advertiser_in Adelaide, the staid morning paper, back in the 50s. The editorial executives went to school together, wore the right tie and drank claret at the Adelaide Club, he recalled from his home in Santa Fe, New Mexico. They interfered all the time and wanted him to stick to safe subjects like the weather. I could not stand it any more, he said.

Oliphant found freedom of expression in the US. As his cartoons were syndicated to hundreds of newspapers, he was not beholden to any editor. If anything drove him, he joked, it was fear of the mortgage. Accolades and prizes, including a Pulitzer, came his way with his pungent, trenchant and imaginative interpretation each day of mainly political American life.

P.J.ORourke told cinematographer David Brill last year that Oliphant was able to make the powerful when they were being ridiculous look ridiculous. He could see into Nixons soul, he said. Hes a one-off.

Hes a rather quiet man, says his wife, Susan. He doesnt say a whole lot.

Im a listener, Oliphant says. Thats how I learn things. He is also a reader of history.

His dark humour has upset sensitive Asian, Arab and Jewish lobbies in the US. Although political figures dominated his works, he said anything related to personal beliefs and religion aroused his audience the most. He infuriated the Catholic church, not for the first time with his notorious drawing of the celebration of spring at St Paedophilias, which he called The annual running of the altar boys, pursued by eager priests.

Humour is a vehicle, he says. It is part of the cartoonists toolbox. It was also what made cartoons powerful. Humour makes things palatable and induces people to look at things they otherwise would not want to think about, he adds.

Cartoonists depend on villains, Oliphant told SBS Dateline at the end of the George W Bush presidency, an era which he said was a match-up of just the perfect villains…Im losing probably the best cast Ive ever had. Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, Condoleezza Rice and Paul Wolfowitz come to mind as well as their leader.

Over time, he drew Jimmy Carter and George W. Bush as caricatures shrinking in size as a reflection of how he regarded their presidency.

Alas, just as Donald Trump and another cast appeared on the scene, fading eyesight forced Oliphant to put down his brush and close his inkwell for the last time. He has no regrets. He described Trump as a trashy person.

One of two cartoons Oliphant did produce early on showed Trump as a child-like member of the Hitler Youth asking a ghoulish Steve Bannon, his then media guru, what he thinks of his outfit.

Why the Nazi clothing? He said he could see Trump coming and the depiction was based on what our parents didnt want us to be.

He once observed that it took six months to get a new president. He described Trump as a caricature of himself. He makes it so easy, he told me. I could not work with someone like him. He conceded that Trumps predecessors did not seem so bad in comparison.

Oliphant is not sure his style of work would survive in todays time-poor era and tens of thousands of words competing around the clock for attention with everything else. Cartoons are a contemplative form of art and people have to think about it for a while, he says.

I do not think art like Pats will pass this way again, ORourke told David Brill. That was because the circus has left town and all we have left are the clowns - and how do you make fun of clowns?

FOOTNOTE. Another innovation of Oliphants was his alter ego in the shape of a penguin called Punk which was there to make what he once called a smart-ass observations. It was inspired by an Adelaide colleague bringing a baby penguin into the office (which later was given to the zoo). Many other cartoonists have copied this style. Punk has now retired to the University of Virginia along with all those thousands of cartoons and other works Oliphant did not give away. UVa Press is planning a book on his life and works.

John Tulloh grew up in Adelaide reading Oliphants cartoons in the Advertiser.

Copyright Pat Oliphant