Jonathan Holmes: Pressing for freedom

July 13, 2022

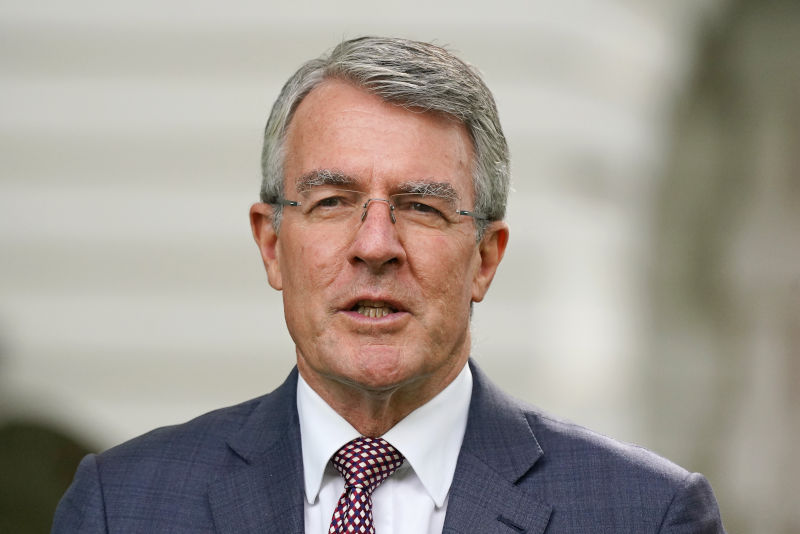

An open letter to Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus QC.

Dear Mr Dreyfus,

Congratulations on regaining the post of Attorney-General, which you held so briefly back in 2013.

Congratulations, too, on your decision to order the discontinuation of the trial of Bernard Collaery. As you make clear, that shameful prosecution required the consent of the Attorney-General a consent which was eventually given by Christian Porter and which is entirely within your power to withdraw.

Your decision gives us reason to hope that this government may take other steps to reverse the trend of the past decade that has led to Australia becoming more secretive, and less accountable, than almost every other comparable democracy in the world.

In Reporters Without Borders 2022 World Press Freedom Index, Australia came a dismal 39th out of 180 nations down from 19th in 2018.

Our position on Transparency Internationals Global Corruption Perceptions Index has been falling too were now 18th, down from 14th last year.

But what a wonderful chance a new Attorney-General has to improve the situation in the next few years! Unless the Albanese government has permanently alienated the teal independents with its sudden decision to reduce their staffing, they and the Greens should give you a solid majority in both the House of Reps and the Senate for any measure that will improve press freedom and government transparency.

And there is a whole raft of measures you can take that will cost the hard-pressed federal budget almost nothing.

First on the list, of course and probably the most expensive is a federal integrity commission. As New South Wales has discovered, an effective anti-corruption watchdog doesnt come especially cheap. But its essential, and its one of Labors core electoral promises.

It was, as you have shown, a simple matter for the federal Attorney-General to halt the prosecution of Bernard Collaery. It would presumably be almost as simple to halt that of Tax Office whistleblower Richard Boyle.

But these prosecutions should never have been launched in the first place.

Helen Hayness Federal Integrity Commission Bill kills two birds with one stone: not only does it set up a proper anti-corruption commission, with teeth; it also provides for a Whistleblower Protection Commissioner, whose job would be to ensure that public service whistleblowers are properly protected, not put on secret trial by politicians seeking to preserve their own or their predecessors reputations.

But I understand that neither your department nor your party likes that part of the Bill. I wonder why not?

A change in Australian law wont do anything to bring the seemingly endless persecution of Julian Assange to a close. But if the US alliance means anything, it surely means that a newly-elected Prime Minister can make it clear to a President whos on the same side of politics that its time this Australian citizen was allowed to come home. So please, keep the PM and his cabinet focused on the need to stop Assanges extradition from the UK to the USA before its too late.

While youre at it, take a another look at the trial of Major David McBride, who (on his own admission) leaked secret documents to the ABC about war crimes in Afghanistan. This is not, as it is often portrayed, a straightforward case of whistle-blowing: although news to the public, the allegations he leaked were already being investigated by the Brereton Inquiry indeed, the leaked documents came from the files of the Armys earlier investigations.

But the McBride case poses an especially dangerous threat to the ability of the media to hold Commonwealth agencies to account. As ABC Alumni has pointed out many times, among the charges that McBride is facing is one of stealing Commonwealth property, contrary to s131.1 of the Criminal Code. And to justify its demand for a warrant to raid the ABC in June 2019, the AFP claimed that it suspected ABC reporter Dan Oakes of the criminal offence of dishonestly receiving stolen Commonwealth property, contrary to s132.1. The maximum sentence is ten years in prison.

A year later, the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions announced that it was not in the public interest to pursue charges against Oakes. But McBride is still facing the theft charge.

What makes the use of this offence more alarming is that the law concerning the leaking of government secrets was recently amended. The new s122 of the Criminal Code provides for significantly tougher penalties than the law it replaces, s70 of the old Crimes Act. But it applies only to the leaking of harmful or inherently harmful information. And it does provide a defence for professional journalists who reasonably believe they are acting in the public interest.

Neither of these safeguards applies to the charge of stealing or dishonestly receiving Commonwealth property. As things stand, anyone who leaks any Commonwealth document, secret or otherwise, and any journalist who receives that document, whether or not it is published, can be charged with a serious criminal offence.

This is one of innumerable similar nonsenses which the Attorney-Generals department has been promising, for years, to put right. It undertook to do a review of secrecy offences back in 2017. In 2020 the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security (PJCIS), of which you were a prominent member, told it to get a move on, and while it was at it, to specifically consider whether the relevant legislation adequately protects public interest journalism.

In early June 2021, I asked the department how it was going. Its reply: The department has completed a survey of Commonwealth secrecy legislationThe survey has identified 11 general secrecy offences, 487 specific secrecy offences and 210 non-disclosure duties.

But it had hardly begun to consider how public interest journalism should be protected from this formidable raft of secrecy offences. Further time may be required due to the complexity of the issues involved, I was told. Well, more than a year later and five years since the review was first called for weve still heard no proposals, seen no review.

Perhaps as the new Attorney-General you can put a rocket under your public servants. Lets see the review of secrecy laws. Lets have some action on protecting public interest journalism. In particular, lets have a directive to the CDPP from the Attorney-General that offences that come within the purview of s122 the leaking or receiving of official information should be dealt with under that law, and not treated as theft of Commonwealth property.

You and your Labor colleagues on the PJCIS had another good idea, which was over-ruled by the coalition majority. Rather than a defence for bona fide journalists who are acting in the public interest, you wanted the new secrecy laws to provide them with an exemption from prosecution. That would mean that instead of journalists having to prove to the court that they reasonably believed they were acting in the public interest, the prosecution would have to prove that they were not bona fide journalists, or that they were not acting in the public interest. That would be a harder bar to surmount.

Why not revive that idea, and apply it to the vast majority of those hundreds of secrecy provisions? It would go a long way towards restoring the balance between obsessive secrecy on the one hand, and public accountability on the other.

And then you could turn your attention to the law of defamation. As its currently interpreted by Australian judges, it is arguably an even more formidable obstacle to the medias attempts to hold the powerful to account than any of the hundreds of secrecy provisions.

The good news is that, led by NSW Attorney-General Mark Speakman, the states have agreed on a set of reforms designed to ensure defamation law does not place unreasonable limits on freedom of expression, particularly about matters of public interest.

Among other important changes, the new Uniform Defamation Act provides a new public interest defence for journalism. Media defendants need only prove to the court that they reasonably believed they were acting in the public interest by publishing.

More important still, the Act specifies that it is up to the jury, not the judge, to decide whether that defence has been made. Judges have almost never found that the media have acted reasonably in publishing matter whose truth they cannot prove. Theres a very good chance that juries will be more inclined to do so.

The problem is that the Federal Court does not offer the option of trial by jury in defamation actions. Thats one reason why it has become the forum of choice for defamation plaintiffs. Its judges have proved to be, for the most part, hostile to media defendants, and willing to award very substantial damages to victorious plaintiffs (or applicants, as it likes to call them).

Whats needed is a simple change to the Federal Court Act to provide that in defamation actions, either side may opt for trial by jury. At a stroke, that would likely return most cases to the state Supreme Courts; it would stop forum shopping, and level the defamation playing field.

So: establish a federal commission against corruption; ditch the Richard Boyle prosecution; provide real protection for public service whistleblowers; push for Assange to come home; ensure the theft offence is not applied to the leaking of information; push your department to complete its review of secrecy provisions; apply an exemption for public interest journalism to all, or at least, most of them; allow media organisations openly to contest applications for search warrants; and amend the Federal Court Act to allow participants in defamation actions to opt for trial by jury.

Not too big a to-do list for a three-year term, surely? It would push Australia back up the Press Freedom Index, and help restore some of the liberties that coalition governments have sacrificed in the name of keeping us safe.

Stopping the Collaery prosecution was a good warm-up. But the real race starts now.

On your Mark. Get set. Go.

By Jonathan Holmes, Chair, ABC Alumni

A longer version of this article can be found at ABCAlumni.net