Lest we forget: Lessons for AUKUS from the Anglo-German naval race

September 27, 2021

In the shadow of AUKUS, there are many echoes of debates from the era of the Anglo-German naval race, 1900 to 1914. Are there any lessons for us?

Before World War I, Britain and Germany competed in a ruinous naval arms race. Britain entered into new ententes (agreements), with France in 1904 and Tsarist Russia in 1907, alliances in all but name. These ententes, initially designed to settle colonial rivalries with France and Russia, grew into security pacts to contain Germany.

What lessons might we draw?

Hose down the military advisers

As British prime minister Lord Salisbury wrote in 1892: “I would not be too much impressed by what the soldiers tell you … It is their way. If they were allowed full scope, they would insist on the importance of garrisoning the moon in order to protect us from Mars.”

Today, Australian military planners are asked to advise on expanding the forces in which their careers are advanced, to advise on the further integration of those forces with the USA and UK, an integration which will open up access to better weaponry, travel, promotion, and prestige. What advice is likely?

Keep perspective

From about 1904, Britain supposedly sought to “contain” Germany, a rising power with a small empire, while securing her own huge empire. Way back in 1894, the Liberal Chancellor Sir William Harcourt asked the obvious: “We have already got the lions share, why should we insist on the tigers also? Not to say the jackals?”

No such perspective today. One side has overwhelming military might and scores of overseas bases. Supposedly, the capability of the USA and its allies is self-evidently defensive, that of Americas rivals self-evidently aggressive. Peter Hartcher told Insiders that the purpose of the new submarines was “to bottle the Chinese fleet up in the South China Sea … [to] create a blockade, under water, to prevent the Chinese navy escaping the South China Sea.” Apparently, this is for Australias defence and not in the least aggressive.

Follow the money

In 1902, Britains National Service League the noisiest lobby group beating up the German peril was founded by the financier Sir Clinton Dawkins. He was head of J.P. Morgans British banking house, J.S. Morgan & Co. Both banks had multiple financial interests profiting from the “preparedness” panics and booming military budgets.

Today, our Australian Strategic Policy Institute gets only 3 per cent of its funding from “defence industries”. Its website features the logos of those donors, Naval Group, Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin, SAAB, Thales, and Raytheon Australia. Of course, this is pure philanthropy and these companies do not crave any influence whatsoever when a giant raid on the public purse is in process.

Watch the lobbies and leagues

In both Britain and Germany from 1900 to 1914, similar military lobbies urged much more spending on “defence” to avert war. In Germany, the Pan-German League, the Navy League, and the Army League all preached “preparedness or peril”. In Britain, the Navy League, Imperial Maritime League, and National Service League, all shouted “readiness or ruin”. All deployed the motto “Si vis pacem, para bellum” (“If you wish for peace, prepare for war”).

Now, everything old is new again. Jon Stanford in Pearls and Irritations invoked the old Latin motto as a headline. Speaking on RN Breakfast last week, Barnaby Joyce also invoked “Si vis pacem …”, as if it were the 11th commandment.

Remember, sticky alliances inevitably entangle

From 1906, British ministers secretly authorised military conversations with the French general staff. When this was exposed in 1911, the government faced accusations of compromising Britains independence. Then, in 1912, Britain arranged a fleet swap with France: more British ships in the North Sea; more French ships in the Mediterranean. Prime minister H.H. Asquith and foreign secretary Edward Grey both repeatedly told parliament that Britain retained a “free hand”. When the crisis came in August 1914, they argued the reverse: it would be dishonourable to disappoint France and Russia, and they declared war.

Today, Scott Morrison assures us from Washington that “as a government, we have to do what is right for Australias national security interests. And I will always choose Australias national security interests”. So, no danger then that the Scarborough Shoal will one day be judged worth the bones of an Australian submariner.

Watch the wealthy run away from the cost

In Germany in 1909, Chancellor Bernhard von Blow fell from office when conservatives revolted against wealth taxes to pay for the big navy. In Britain in 1909, “the peoples budget”, to pay for Dreadnoughts and pensions, provoked a Die-Hard revolt and a constitutional crisis. In 1910, Admiral Charles Beresford MP, a Big Navy blowhard, denounced a motion increasing the income-tax rate (to one shilling and tuppence in the pound). He told the parliament that a grand struggle was underway “sea power versus socialism”.

Today, if the enormous cost of the submarine program were to be paid for by new imposts on wealthy Australians, Morrison would fall. Can any reader imagine him explaining that, so dire is Australias peril and so urgent the need to buy submarines, that he was abandoning stage three income-tax cuts, ditching the capital gains tax discount, and limiting negative gearing and franking credits? Fat chance.

Beware all promises of deterrence

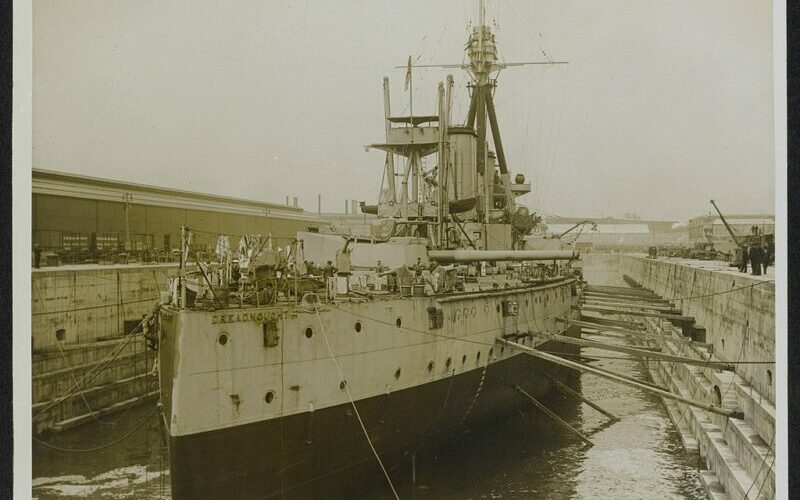

The people of Britain were assured that only keeping naval superiority could avert war and that the new HMS Dreadnought of 1906 would do it. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz assured the German people that even building a fleet that posed a “risk” to Britain would deter war. But superiority provoked insecurity. Technology overleapt itself. The Dreadnought-class battleships of 1906 had 12-inch guns; the Orion-class of 1910 had 13.5-inch guns; the Queen Elizabeth-class of 1913 had 15-inch guns. In 1914, 18-inch guns were ordered. Admiral John Fishers dream ship, HMS Incomparable, had 20-inch guns. And war broke out anyway.

Today, strategic experts are all raised on peace-through-strength platitudes, and missiles-for-peace memories of the 1980s. They pay homage to their one-true-household-God Deterrence. Even the “risk” theory is recycled. Echoing Tirpitz, John Blaxland told RN Breakfast that “we have to have a capability that makes them [China] think twice, thats the whole point of deterrence”.

Dont expect rational threat assessments

In the Dreadnought era, oceans of ink were spilled to persuade the British people that Germany was a singular threat, and Britains allies were peace-loving. In fact, between 1900 and 1914, Britain fought a war in South Africa (1899-1902), Britains ally Japan fought a war with Russia (1904-05), France risked European war twice to further her ambitions in Morocco (1905-1911), Japan annexed Korea (1910), Italy (whom Britain hoped to lure into her alliance) fought a war in Libya (1911), and Russian ambitions in the Balkans provoked two wars there (1912-13).

Todays spruikers block out inconvenient history and paint devils on walls. Tom Tugenhadt MP, chair of Britains Foreign Affairs Committee, told RN Breakfast that the UK, USA, and Australia were simply reacting to China, and that China shouldnt complain: “Its slightly like an armed guy moving into a bar and complaining when people decide they might need to protect themselves.” So, in this fantasy world, the USA, the UK, and Australia are apparently unarmed barflies. Forget the catastrophic American-led, 20-year military intervention in Afghanistan and Iraq, surrounding Iran, and near to Russias and Chinas borders.

Dont expect rational choices to prevail

The ultimate irrationality of war the settling of international disputes by high explosive was obvious for Germany and Britain. By 1914, they were each others most valuable trading partners. In 1911, Germany relied upon the British Empire for 18.3 per cent of her imports, and sold to the British Empire 17.7 per cent of her exports. The British Empires leading export destination was Germany, at 8.2 per cent, while 10.4 per cent of its imports came from Germany. Nonetheless, from 1914 to 1918, the German and British attempted to slaughter each others most vital customers. Britain endured almost a million war dead, and Germany almost 2 million. Lest we forget.