Many Australians with a Chinese background feel caught ‘between a rock and a hard place’

December 11, 2020

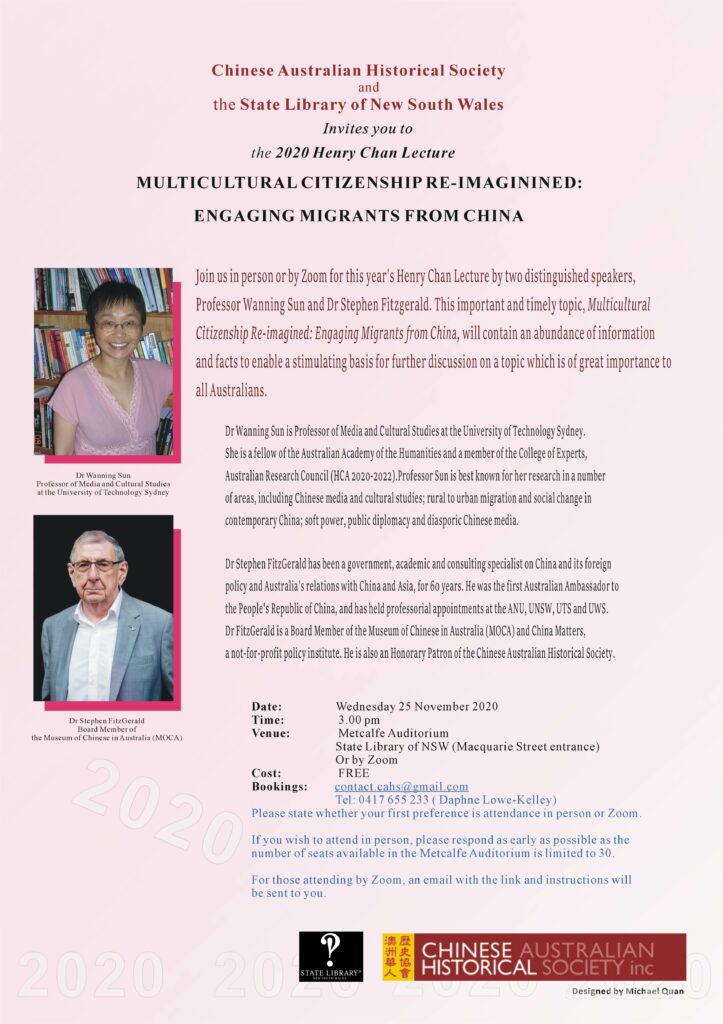

I was invited to give the annual 2020 Henry Chan lecture at a time when Chinese-Australians had well and truly become objects of suspicion and distrust. I have been doing research on Chinese-language media in the Chinese diaspora for two decades.

The word ‘diaspora’ has been a jargon word in academia, which often is used without any hint of positive or negative connotation. Diaspora studies is now a well-established sub-field of scholarly research, and there are quite a few refereed journals dedicated to diaspora studies.

In recent years, however, I have noticed a curious trend of weaponizing the term. English-language mainstream journalists have now not only learned to properly spell and pronounce the word, they have also taken to using the term with gusto when referring to members of the Chinese community, especially those from China. Politicians love to use this term as a short cut. A few months ago, acting Immigration Minister Alan Tudge observed ‘with regret’ that, instead of being ‘proud Australians’, some communities are still seen by their former countries as ‘their diaspora’.

The default assumption about the political connection between the Chinese diaspora and the Chinese government is most clearly evidenced in Senator Abetz’ request to the three Chinese Australians in a senate inquiry into issues facing diaspora communities in Australia. He asked them to denounce the Chinese Communist Party.

As Louise Edwards, UNSW’s Scientia Professor of China Studies recently comments, “diaspora people are only really heard when they are useful to fulfilling some other agenda’. She reminds us that some groups, such as the white diaspora, don’t even get called “diaspora” because the term has become a way of marking those who are racially, politically or culturally different from ‘us’.

When our Prime Minister expressed outrage and demanded apology from the Chinese government over Zhao Lijian’stweeted image, Mr Tudge promptly held a teleconference with some Chinese Australian community leaders. In his media statement, Mr Tudge said the image tweeted by Zhao was ‘shameful and offensive’, and he was glad to report that every one of Chinese community leader who spoke at the teleconference ‘was just as appalled by the fake image’.

Upon reading Tudge’s statement, I wondered: if anyone from the Chinese Australian community did not share Mr Tudge and our Prime Minister’s outrage, would he or she dare to speak up? Would they be deemed less Australian or even ‘unAustralian’? We have seen a wide range of opinions in the mainstream Australian public in response to the Chinese tweet and our Prime Minister’s reaction, so why shouldn’t we expect a similar level of pluralism within the Chinese Australian community?

Reading Mr Tudge’s praise of the Chinese community leaders for saying the ‘right’ thing, I was again reminded of what Jan Fran said to Osmond Chiu in a recent episode of the Q&A regarding Senator Abetz’ questioning: ‘It is just a confirmation that you, actually, are not really Australian, that you are here conditionally… You are here on a good-behaviour bond.’

I know that I might sound like what some may describe as an ‘ungrateful migrant’ – after all, why whinge about Mr Tudge, who was full of praise for the 1.2 million Chinese Australians? But the honest truth is that instead of feeling privileged by this special treatment – Mr Tudge didn’t go to anywhere else except the Chinese Australian community – I felt, for the lack of a more colloquial word, ‘interpellated’. I felt like a child whose parent hovers over her and says, ‘Look at that child. He’s naughty, isn’t he? Now we don’t want to be naughty like that, do we?” As Jan Fran said to Osmond, ‘you need to be constantly proving your loyalty to this country. That is not asked of other people.’

Many people in my WeChat groups have taken up Australian citizenship and consider themselves Australian. Some have mixed feelings in response to Mr Tudge’s praise. Many people in this first-generation migrant cohort experience what I call ‘chronic Chinese influence fatigue syndrome’. Some say, ‘why can’t I just be left alone and get on with our lives? ‘I no longer care about China-Australia relationship. I just don’t want to be a pawn between them’.

It is against the backdrop of this complex political reality that I wrote this lecture. The conceptual starting point for my lecture was the fact that Australia’s multiculturalism is in trouble, partly due to the fact that China is not only our largest trading partner, but also, in recent years, has been the largest source of immigrant population. In my talk, I engage with Professor Andrew Jakubowicz’s work and ask how the ‘Chinese question’ could help ‘modernize’ Australia’s multiculturalism. And I offer a two-pronged pathway: engagement and respect for human rights.

The lecture starts with a brief review of recent changes in Chinese migration to Australia in the last four decades, pointing to a dramatic demographic shift in the Chinese migrant community in Australia in terms of language and cultural practice. The first main message from this overview is that the PRC migrant community is marked by diversity in terms of social values, political views, cultural sensibilities, and consumption habits. They by no means constitute a single interest group. The second message is that there is a high level of ambivalence on the part of many individuals in this group about their identity and their sense of belonging, and many feel stuck between a ‘rock and a hard place’.

This brief history is followed by a review of the main issues facing first-generation Mandarin-speaking migrants, as well as those facing Australia’s multiculturalism as a result of the ‘Chinese question’. Here, I discuss a set of push and pull dynamics which impact on this cohort’s capacity to develop a sense of belonging and feeling at home in their adopted country. While the pull factors include DFAT’s public-diplomacy-through-diaspora agenda and China’s soft-power-through-diaspora agenda, the push factors in Australia include anti-Chinese racism, security establishment’s tendency to see them as a risk, and the current political discourse that mostly questions their loyalty.

Pitching my message to the Australian government, media, older and southern dialect speaking Chinese communities – as well the first generation mainlander migrant cohort itself – I suggest that engagement with this new migrant cohort is a pre-requisite to their integration. Sadly, so far, this engagement is not happening – some people in the Cantonese speaking community eye mainlanders with suspicion, even hostility. And many mainlanders find it difficult to communicate with Chinese-Australians who don’t speak Mandarin.

Finally, revisiting Andrew Jakubowicz, I ask how Australia’s multiculturalism can be modernized through a genuine attempt to engage first-generation Chinese migrants, on the one hand, and an ungrudging respect for their human rights, on the other. I suggest that the most effective way of starting this engagement is to treat members of this cohort as rights-bearing citizens, and, first and foremost, as Australians.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wghOI6bw-D0&ab_channel=ChineseAustralianHistoricalSociety

“This was the 4th Henry Chan lecture sponsored by the Chinese Australian Historical Society, in association with the State Library of New South Wales, the original intent of which was to bring China based scholars of Australian studies to Australia. In response to pandemic restrictions this aim has broadened to include Australian based scholars discussing topics of value and interest to the Chinese Australian and broader Australian community. The topical nature of Wanning Sun’s lecture only demonstrates that history begins now.”

- Chinese Australian Historical Society (CAHS)