Nature's right: a world with limits, to fossil fuels and population

October 31, 2021

The lessons of climate change are in the numbers, but the fundamental lesson is the most difficult one on our human numbers.

First, a simple question: how much of the world would you leave to nature?

More than three-quarters of all nations, including all the big and developed economies, are in a state of biocapacity deficit, taking more from their ecologies than their territories regenerate.

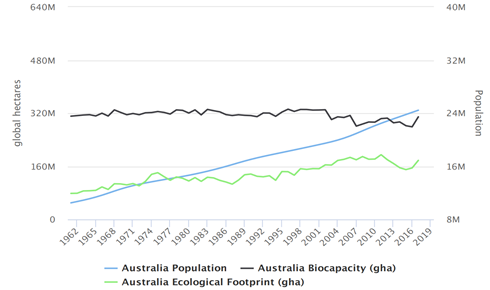

Australia is one of the luckiest of those comparatively few countries with remaining biocapacity reserves, but for how long? In the graph below, the black line is the biocapacity the amount of living matter Australias ecosystems can regenerate.

Between 1961 and 2017, Australias population (the blue line) increased by 233 per cent, from 10.4 million people to 24.5 million. Australias Ecological Footprint of consumption (the green line) increased with it, eating away at the biocapacity reserve.

The Ecological Footprint metric is the global hectare or gha, a measure of land area which varies according to an areas biocapacity, so that the gha has a constant yield around the world. It is uniquely useful in being a single metric reporting on all aspects of ecosystem services.

Climate change had been drying out the forests of the east coast and Western Australia. Then came 2019, Australias hottest year on record, and the Black Summer bushfires erupted. The nations biocapacity of 296 million global hectares was reduced to 153 gha, less than the peoples 160 gha Ecological Footprint of consumption.

David Lin, chief science officer of Global Footprint Network (GFN), says the think tank calculated the impact of last summers devastating wildfires in Australia. Our research found that Australias biocapacity reserve turned into deficit for that year.

Setting aside the human loss, billions of animals were incinerated. GFNs Professor Pat Hunscom comments: This abrupt change from having a large biocapacity to running a biocapacity deficit is a tragedy. But the even bigger tragedy is the loss of biodiversity due to the destruction of mature ecosystems which were habitat to many unique species.

The Ecological Footprint and Biocapacity accounts were created in the 1990s by Professor William Rees and Mathis Wackernagel at the University of British Columbia, Canada. The framework was central to Wackernagels founding of the Global Footprint Network in 2003. It answers the question: How much nature do we have, and how much do we use?

GFNs annual National Footprint and Biocapacity Accounts derive from all nations datasets, international trade models and bodies such as the United Nations Environment Program and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. The datasets go back as far as 1961, revealing important trends. The Ecological Footprint is easily the most well-known of many sustainability measures. It informs campaigns by WWF, the worlds largest environment group, and its international Earth Overshoot Day.

Over the period 19612017 the carbon, or greenhouse gas, footprint has grown enormously to 60 per cent of the world ecological footprint. The energy transition plus carbon sequestration in soil and sea will bring this down, hard as it may be.

But reductions in the remaining 40 per cent of the footprint which provides all of humanitys ecosystem services on land and water will be harder. Its hard even to frame the problem in a way which people will accept, because the problem is ourselves, our population number and our way of life even our beliefs. In a world which we have pushed into ecological deficit, the problem ranges humanity against biodiversity. And to date, we have failed to meet all internationally agreed biodiversity goals.

In 2020, Wackernagel published Shifting the Population Debate: Ending Overshoot, by Design and Not Disaster.

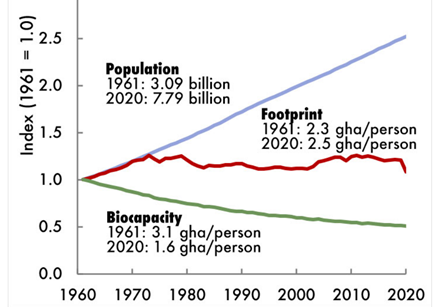

Between 1961 and 2017, world population increased by 252 per cent. Over this time, Ecological Footprint per capita increased only slightly, but biocapacity per capita decreased by nearly half. Most of this fall in biocapacity was caused by the population increase, with attendant inequalities of consumption.

Wackernagel: Global Footprint Networks approach is consistent with the one proposed by Holdren, Ehrlich and Ehrlich which they call IPAT (the concept that environmental Impact equals Population x Affluence x Technology.) The Ecological Footprint translates this concept into real numbers.

Humanity currently demands 56 per cent more from our planet than its ecosystems can renew. To maintain 85 per cent of the worlds biodiversity, human demand can only use half of what the planet can provide.

Arguing the urgency of reducing population, Wackernagel comments: Through forward-looking decisions, we can turn around natural resource consumption trends while improving quality of life it has some of the highest, cost-effective long-term benefits, not just for the environment, but for health and education outcomes, tightly linked to equal rights for all people independent of sex, gender, sexual orientation, age etc., which we at Global Footprint Network would advocate for even if it had no environmental benefit.

Its time to infuse some empowering facts into the public [population] debate There is a humane choice whether there will be 4 or 11 billion people sharing our planet in 2100.

Critics of the Ecological Footprint method have said that it fails to reveal environmental problems such as soil depletion and species extinction threats. In fact, the Global Footprint Network is not an in-field environment organisation; what it provides is environmental accounting using many sources of big data. GFN admits that there are limitations, but a recent alliance with York University Ecological Initiative in Toronto, and their establishment in 2020 of FoDaFo (Footprint Data Foundation) provides any researcher with increasingly rich environmental data from all nations, free of charge.

Environmental accounting is, or should be, the essence of the population debate an enquiry into what is best for all humans and the planet. But, says Wackernagel, it can roadblocked by:

- Morally proscriptive, ideological, religious or polarising arguments,

- Horrific past experiences of ‘’eugenic’’ policies including forced sterilisation,

- Economic fear that without expanding populations there will be no wealth and security,

- A singular focus on abortion,

- Accusations of racism.

These attitudes may be especially corrosive in North America, but the Australian population debate has also had its problems, especially with the elite growth-at-all-costs boosters in politics, business and the media.

Shamefully, even some large environment groups have avoided speaking out on this population growth dogma. I remember a one-day Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) meeting on population when the two ACF councillors resolutely steered well clear of the topic all day. The ACF used to have a population policy but they discarded it.

It is vital we understand the scale of impact that humans have on other animal species, says Tim Doherty, a wildlife ecologist at the University of Sydney. He is lead author of “Human disturbance causes widespread disruption of animal movement”, an analysis of 208 separate studies on 167 animal species in all continents, ranging from the 0.05 gram sleepy orange butterfly to the more than 2000 kilogram great white shark.

The meta-analysis reveals that hunting and tourism in wilderness areas, especially during animal breeding periods, are especially problematic, leading to reduced animal fitness, lower chances of survival, reduced reproductive rates, genetic isolation and even local extinction.

Doherty says: Reducing negative impacts of human activity will be vital for securing biodiversity in an increasingly human-dominated world.

Australia is the home not just for us but for the great number of unique species in highly biodiverse ecologies. We have destroyed much of this irreplaceable wealth, and now Australia tops the chart of sizeable nations Ecological Footprints.

Population growth is still being pushed in many quarters. The _Australian Financial Review_s editorial of October 15 stated: ‘‘A Bigger Australia to push up growth, pay down debt’.

Jenny Goldie, national president of Sustainable Population Australia, wrote in response:

We are long past the time when we can focus only on any short-term economic benefits of massive population growth and ignore the social and environmental ramifications. Nor can we ignore the moral aspects of poaching skilled workers from other countries while we fail to adequately support our universities, TAFEs and other training institutions to provide the skills we need.

What right has Australia to take the talents of other countries who have borne the cost of training them? Infrastructure costs have to be weighed against any economic gains we might achieve from a mass influx of people.

Economists can no longer ignore the environmental consequences of population growth, not least the loss of other species habitats including the koalas from urban and agricultural expansion. And a critical issue is the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in order to meet our climate change targets.

Eminent professor Paul Ehrlich tells us we are now witnesses to and principal actors in the Earths sixth mass extinction. Thousands of populations of critically endangered vertebrate animal species have been lost in a century, indicating that the sixth mass extinction is human caused and accelerating Our results re-emphasise the extreme urgency of taking massive global actions to save humanitys crucial life-support systems.