North Asian Summit: hedging against the United States?

June 4, 2024

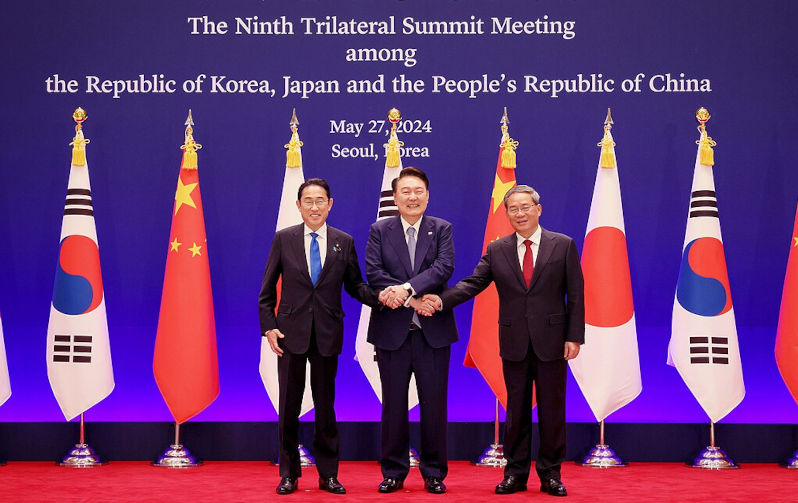

The Prime Ministers of China, Japan and South Korea met in Seoul on 27 May to resume regular annual meetings which began in 2008 and were held annually until 2019, when they were interrupted by COVID and “aspects of the international situation”.

The PMs issued a joint statement after their meeting which was strong on practical cooperation and careful with touchy political subjects like North Korean nuclear, Taiwan and the South China Sea. This caution was reflected in remarks by the Chinese Premier outside the meeting, when he said that “China, Japan and South Korea should appropriately handle sensitive issues and points of difference, and take care of each other’s core interests and major concerns.”

Although in other comments outside the meeting the leaders maintained their emphasis on unexceptionable areas of future cooperation, it seems likely that two of the shared factors behind the series’ resumption were concern about the consequences of a possible second Trump Presidency; and concern about the general unimpressiveness of the contemporary United States—including in its economic policy towards the Asia-Pacific.

For China, US sanctions in the high-tech and supply chain areas, and the prospect of more of them, would have been a very important additional factor leading it to look favourably on possible hedging mechanisms. In this regard, Japan’s enthusiastic participation in the summit, and PM Kishida’s later positive remarks to a visiting Chinese senior official (see below), are one of the most interesting aspects of the events.

Reactions to the meeting varied considerably. Writing in the context of an immediately following trip to Japan by the head of international liaison for the Chinese Communist Party, a “South China Morning Post” commentator referred matter-of-factly to the completion of the summit, which it described as having aimed “to boost cooperation on various fronts and seek greater regional balance of power”.

It’s highly doubtful that this assessment was shared by “the one who wasn’t there”, North Korea, which responded to the event by trying to launch a spy satellite, forbidden by the UN, which crashed. Also, according to a report in “The Australian”, on 29 May it sent “balloons full of garbage, toilet paper and suspected animal faeces” into the South. Kim Jong-un’s sister, Kim Yo-jong, mocked the “goblins of liberal democracy” in Seoul for complaining about the balloons!

(In fact the joint statement issued after the summit was circumspect on North Korea, not including previous calls for “the complete denuclearisation of the Korean peninsula”, though agreeing to continue to “make efforts for the political settlement of the Korean Peninsula issue”, and otherwise re-affirming participants’ respective positions.)

The various “areas of practical cooperation” mentioned in the statement were people-to people exchanges; responses to climate change; economic cooperation and trade; public health and aging; science, technology and digital; and disaster relief and safety. Of these there was particular emphasis in outside comment on “economic cooperation and trade”, and in particular on “speeding up negotiations for a Trilateral Free Trade agreement”. These had begun in 2012 but have not made much progress, despite the enormous volume of trade between the three. The three said they aimed at a “free, comprehensive, high quality and mutually beneficial economic partnership agreement”. Chinese premier Li added “supply chains” as an issue, and Chinese officials have spoken of an eventual FTA being integrated into the RCEP framework—an “RCEP-plus”.

Of course it is too early to tell whether the foreshadowed efforts at tripartite cooperation will even take place, let alone whether they will be fruitful. But the three are serious countries with mighty economies, and like the rest of us are facing an uncertain and unstable world. Perhaps this recent piece of diplomacy is best seen as a response by China to actual and foreshadowed actions against it by the US, as a somewhat surprising piece of hedging by Japan and South Korea, and as a signal that all three countries regard the United States as a somewhat unreliable partner for the future.