Old trees are good trees

May 26, 2024

Big old trees are few in number but store lots of carbon. Loopholes found in Victoria’s ban on native tree logging. Great Barrier Reef bleaches for fifth time in eight years.

Which trees hold the most carbon?

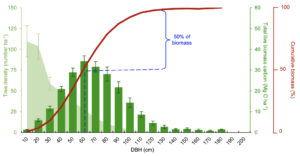

The somewhat complicated figure below illustrates a very important point: the few, older, larger trees in primary forests store at least half of the carbon in the forest.

Let me try to explain by talking you through the figure, which is based on data from naturally regenerated European forests that contain native tree species of various ages and no evidence of human activities. Such ‘primary forests’ have the highest level of ecosystem integrity and store the largest amount of carbon.

The light green shaded area (scale on the left) represents the distribution of tree density by tree diameter (horizontal axis). Most of the trees in the forests are small diameter trees (less than 30cm, say) and there are very few, very large diameter trees (over 90cm, say).

The dark green columns represent the carbon stored in all the above- and below-ground living biomass of trees of various diameters. Most of the biomass is associated with the moderate number of large trees in the 50-80cm diameter range and the very few trees larger than this.

The red curve represents the cumulative biomass over the range of tree sizes, with the blue line demonstrating that half of the total biomass is associated with the 15% of trees with diameters above 60cm, although this varied across broadleaf, conifer and mixed forests.

The article from which this figure is taken makes some other important points:

- Not all the carbon in the forest is contained in the above-ground trunks, branches, leaves, etc. The roots and dead biomass (e.g., dead trees, fallen branches and leaf litter) together contain approximately 40% as much carbon as the visible parts of the trees.

- The carbon stocks in primary forests have been underestimated by about 50%.

- Forests are being maintained at below their maximum carbon stocks. This represents a lost opportunity for drawing down and storing more CO2 from the atmosphere.

- Forests managed for commercial purposes rarely contain any large old trees.

- The protection and restoration of primary forests is a critical action for climate mitigation.

Has Victoria really stopped logging native trees?

There’s been much celebration among conservations about Victoria’s decision to stop the logging of native forests from January 1st this year. However, David Lindenmayer and colleagues, what would we do without them?, have identified three kinds of logging that haven’t stopped and look set to continue for many years:

- Fuel breaks – claimed to assist with fire prevention and management. The felled trees, some over 200 years old, go to timber mills.

- Salvage logging – where logs damaged by natural disturbances such as windstorms and fires are sent to sawmills and firewood yards. The authors describe this as ‘the most destructive form of logging, worse than high-intensity clearfelling’ as it hinders soil recovery and removes habitat for plants and animals for decades.

- Logging on private land – where there is weak if any regulation.

Whether these continued forms of logging are designed to protect human life and habitations, the forests or the logging industry is open to debate.

Great Barrier Reef bleaches yet again

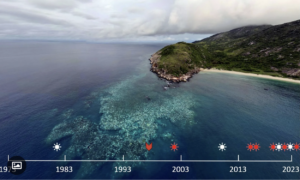

In the first few months of 2024, the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) has experienced its fifth mass bleaching event in the past eight years. Such events were extremely uncommon but global warming and higher ocean temperatures mean that this is no longer the case.

The white suns indicate localised bleaching at Lizard Island at the northern end of the GBR. Red suns are mass bleachings. The red arrow was the first global mass bleaching event.

For the first time this year, the southern, middle and northern sectors of the GBR have all been affected, as clearly visible in the map below which shows the temperature anomaly (the amount by which the water is colder or hotter than usual) on March 4th. The water temperature has been dropping recently but this week it is still hovering just below 27oC.

The extended period of high water temperature around Lizard Island has caused coral death rates of up to 80% this year. The photo below was taken by Lyle Vail, co-director of the Lizard Island Research Station, on April 21st. The dull brown corals are dead and almost all the others are bleached.

If you have 30 minutes and a wish to learn more about coral bleaching on the GBR and how the reef has responded in recent years, I thoroughly recommend watching the 2023 Talbot Oration by Ann Hoggett, also a co-director of the Research Station.

Unfortunately, the media mostly reports the bleachings as one-off events and the seriousness of recurrent bleaching is not getting through to the public:

‘The real message from the 2024 global bleaching event is NOT that corals are once again bleaching around the world. The reef science community has been doing its best to get the seriousness of the situation out there. BUT, the media are NOT conveying that message. They are stuck on bleaching events as a series of one-off events that are terribly sad, but just another nature story.’ Professor Peter Sale.

Paris Agreement’s next big test

It is doubtful whether the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change has delivered much over the last 8 years in terms of actually reducing greenhouse gas emissions globally. It is, however, important to recognise three things:

- How bad things were before December 2015: there was no international agreement to limit global warming.

- The Agreement committed the nations of the world to limit global warming to no more than 2oC (considered at the time to be reasonably ‘safe’) and to strive for less than 1.5o

- The Agreement established a process for encouraging each nation to make a fair contribution to achieving the 2oC goal and for monitoring progress. (It would be nice to be able to say ‘ensuring’ rather than ‘encouraging’ but the agreement lacks any mechanism for forcing nations to act to reduce their emissions.)

The core of the implementation process is that nations agreed to submit every five years targets and commitments (Nationally Determined Contributions or NDCs) for reducing their emissions and that each round of commitments will be stronger than the last. Nations are required to submit their next round of NDCs which cover the period to 2035 by early 2025.

The NDCs submitted to date have been woefully lacking in ambition. Based on current commitments, the most realistic estimate is that the world is currently heading for global warming in the very risky 2.5-2.9oC range.

While many nations have committed to reach net zero emissions by 2050, greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase and the carbon budget for keeping warming under 1.5oC will be exhausted in the next 3-6 years – i.e. well before 2035, let alone 2050. It is clear that the targets and commitments submitted in this coming round of NDCs need to be much more ambitious than in the past.

The World Resources Institute has suggested to the governments of the world a five-point plan for greater ambition and success in combating climate change:

- Set national 2035 targets and revise 2030 targets to align with the goals of net zero emissions and limiting warming to 1.5o For instance, reduce current CO2 emissions levels by 60% by 2035 and commit to reducing all greenhouse gases, not just CO2. Needless to say, wealthy countries should be even more ambitious.

- Accelerate just transitions across all public and private sectors, including ambitious time-bound targets for each sector of the economy. Shifting to resilient food systems that halt deforestation and reduce emissions is particularly important.

- Build resilience to the increasing impacts of climate change (heatwaves, wildfires, storms, droughts, sea level rise, etc.) across all aspects of society.

- Spur investment in environmental sustainability to ensure targets are met and strengthen governance, transparency and accountability in all levels of government and the private sector.

- Put people’s health, jobs, education, communities, security, etc. at the centre of climate action.

The WRI baldly states that ‘By 2035, the world needs to be on a radically different pathway if we have any hope of overcoming the climate crisis. The NDCs that countries submit next year will show in black and white which countries are committed to slash emissions and accelerate adaptation quickly enough to get there.’

What’s the chance of Australia’s next NDCs demonstrating commitment to slashing emissions and accelerating adaptation quickly enough?

Muscle, coal and oil

There is much discussion of energy transition these days but, of course, this is not the first time that there has been one – although it may be the first time that one has been planned centrally rather than being imposed on communities out of the blue, so to speak, by inventors, entrepreneurs and robber barons, and it is certainly the first time one has been planned on a global scale.

The Trent and Mersey Canal was built in the 1770s to link the two English rivers and provide a safer and smoother mode of transport for, amongst other things, Josiah Wedgewood’s pottery. I took the photograph below at Stone, about an hour south of Manchester, six weeks ago (note the early morning frost).

‘18th, 19th and 20th’