Exploited Pacific Island workers applying for asylum

May 19, 2022

One of the symptoms of exploitation in the Pacific Access Labour Migration (PALM) Scheme is the number of workers who run away from their employer and then apply for asylum.

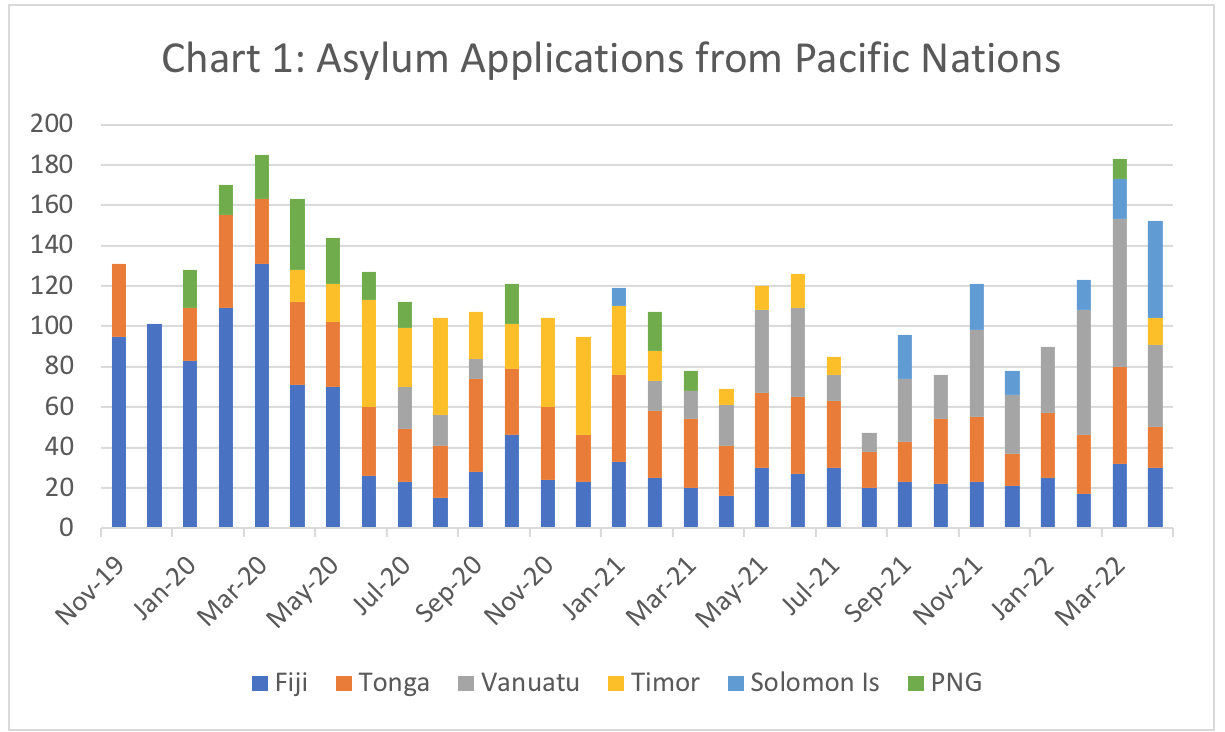

Since late 2019, over 3,500 people (mostly on PALM visas) from Pacific Islands and Timor-Leste have applied for asylum (see Chart 1).

The composition of nations from which these workers are applying for asylum has shifted from mainly Fiji in 2019 and early 2020 to Vanuatu and Timor through most of 2021. In more recent months, the Solomon Islands have provided a larger share. The numbers from Tonga have remained relatively stable at around 30-40 per month. By comparison, few are from PNG, Samoa, Kiribati and Tuvalu.

The success rate of these asylum applications is very low. In April 2022, there was possibly one applicant from the Solomon Islands who was successful.

In March 2022, there were 15 successful applicants from PNG and possibly one or two from Samoa and Tonga. In February 2022, there may have been one from PNG. In January 2022, there were six from PNG who were successful and possibly one or two from Fiji. In November 2002, there may have been one or two from PNG, Samoa and Tonga.

Most applicants, other than those from PNG, would know they have little chance of success. The ones who are successful from PNG are unlikely to be on a PALM visa and more likely involved in politics in PNG.

But by lodging an asylum application, the workers are provided a bridging visa with which they can also apply for work rights. That maintains their lawful status in Australia at least until their primary asylum application is decided which can take a year or more.

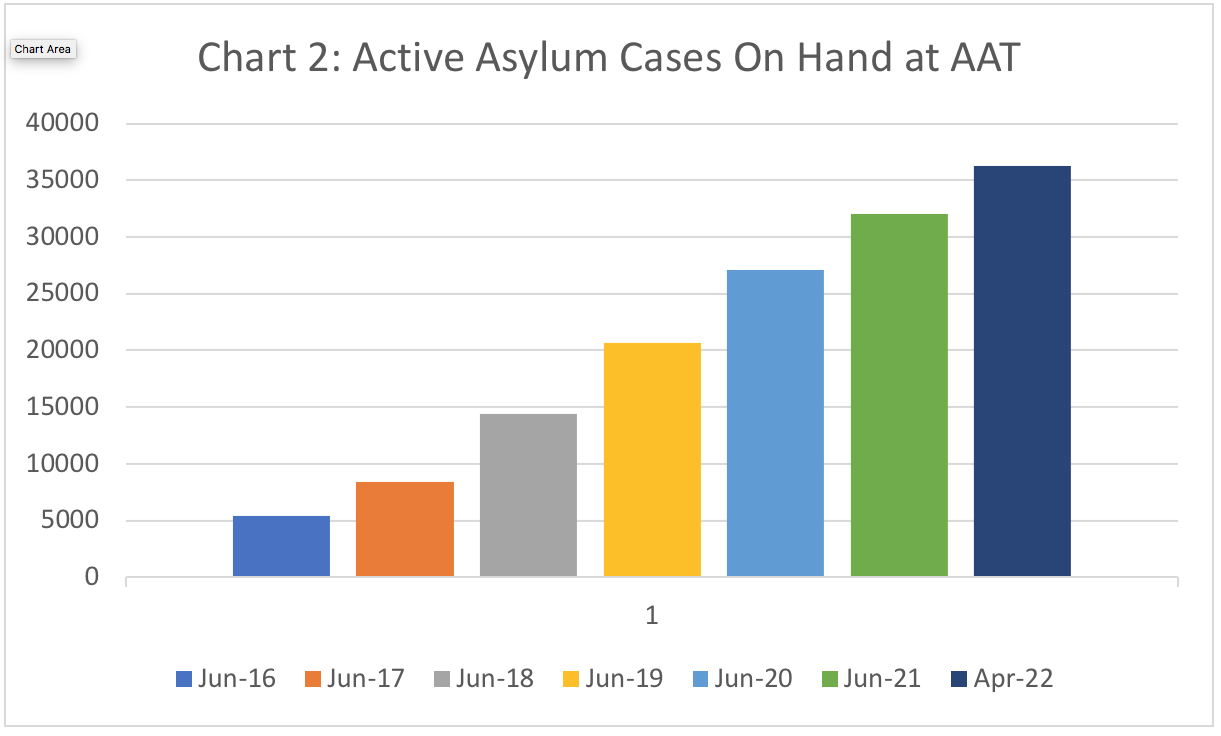

A further application to the AAT can secure another bridging visa where the backlog is so large (over 36,000 at end April 2022), it may take another year or two to process the AAT appeal (see Chart 2).

Because few PALM Scheme workers arrived in Australia during the pandemic, asylum applications from nationals of Pacific countries declined during the latter half of 2021 to around 60 to 80 per month. To date in 2022, there has been an increase to around 100 to 150 per month.

It should be noted the average cost of processing asylum applications is by far the highest of any form of visa application the asylum backlog at the primary stage is around 27,000. These costs are even larger at the AAT where the backlog is over 36,000.

Neither the Department of Home Affairs nor the AAT have the resources to cope with their current massive asylum backlogs let alone dealing with a further surge in such applications.

The migration management part of the DHA budget is being cut from $2.6 billion in 2021-22 to $1.7 billion in 2023-24. That is before the extra efficiency dividend the Government has announced.

The big unknown is that with both major parties committed to giving priority to significantly boosting PALM Scheme visa numbers to supply farm labour, as well as meat processing workers in abattoirs, will asylum applications also surge if these workers continue to be exploited?

The number of people in Australia on other temporary employment visas (essentially a PALM visa) from Fiji, Kiribati, PNG, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Timor, Tuvalu and Vanuatu increased from 5,550 at end June 2020 to 16,330 at end March 2022.

Without globally unprecedented action, the exploitation and abuse of these workers will be turbo-charged as the number of PALM workers is ramped up and especially if there is a downturn in the labour market.

No nation has successfully dealt with this challenge, particularly those in North America and Europe. We should not pretend we can easily do this when all others have failed.

But what happens to the asylum seekers once their asylum applications have been refused at both primary stage and the AAT?

The answer is very little.

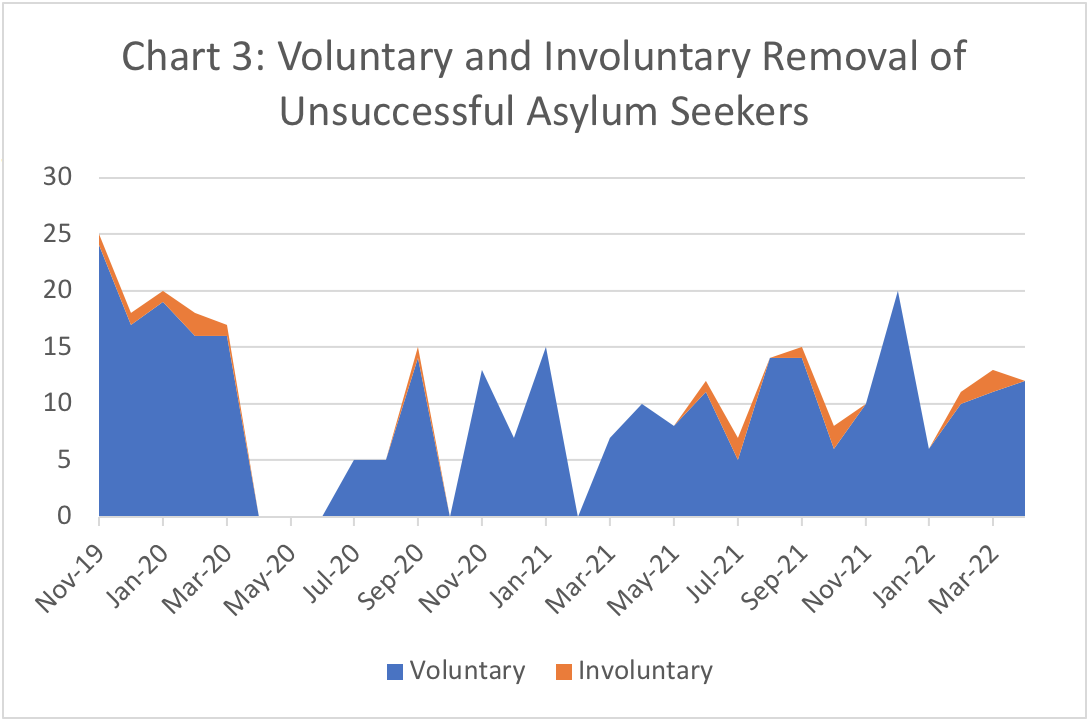

Australian Border Force (ABF) simply does not have the resources to locate and remove unsuccessful asylum seekers (see Chart 3).

In most months, around 10-15 unsuccessful asylum seekers are removed voluntarily. Only one or sometimes two unsuccessful asylum seekers are removed involuntarily each month. On average, the AAT makes around 500 decisions per month with around 90 percent being refused.

The unsuccessful asylum seekers that remain in the Australian community (over 30,000 and growing and another 36,000 at the AAT) are at even greater risk of exploitation as they have no work rights, no access to social support or to Medicare.

Yet Government has no plans to address this other than to increase the efficiency dividend making it even more unlikely anything of substance will be done.

Not surprisingly, difficult problems just get pushed aside.