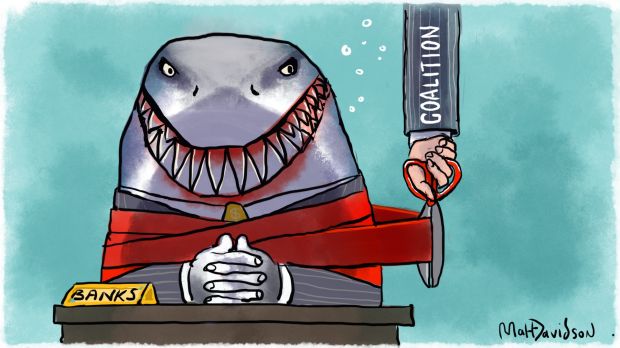

PETER MARTIN. How the Coalition ran interference for the banks.

April 27, 2018

The Coalition wasn’t merely asleep at the wheel when it came to the practices being exposed at the banking royal commission: it pulled out all stops to allow some of them to continue, including attempting to circumvent the will of parliament, in an extraordinary 12-month burst of activity that began within weeks of its election.

It had inherited Labors Future of Financial Advice Act, legislated in 2012 but not due to take full effect until mid-2014, 10 months after the election that swept it to power.

The result of a parliamentary inquiry and years of agonising about how to protect consumers in the wake of the collapse of investment schemes including those run by Storm Financial, Timbercorp, Opes Prime, Bridgecorp, Westpoint, Trio and Commonwealth Financial Planning Limited, the law banned secret commissions and, from that point on, required financial advisers to put the interests of their clients ahead of their own.

Actually, it came into effect on July 1, 2013 during the life of the Gillard Labor government, but the Securities and Investments Commission decided to take a facilitative compliance approach, meaning it wouldnt enforce it until July 1, 2014, which turned out to be after the Coalition took office.

The law banned kickbacks and commissions paid to advisers by the makers of the products they were selling, which for the dangerous products had been extraordinarily large. Advisers putting retirees into Storm Financial had been paid 6 to 7 per cent of the amount invested. Advisers putting clients into Timbercorp had been paid 10 per cent plus an ongoing fee for as long as the funds stayed there.

Labors law wound back, but did not completely eliminate, the ability of banks to reward their staff for recommending the banks own products, and it only applied prospectively. Existing kickbacks could remain but clients would have to be told how much money was being taken out of their investments each year and would have to approve.

Once every year they would be given a statement explicitly telling them how much of their funds was being siphoned off to pay their adviser. Once every two years they would be asked if they wanted it to continue. If they said “no” or said nothing (which would be the case if they were dead, or the adviser had lost contact with them) the outflow would stop.

Clients who felt they were continuing to get good service from their adviser could allow the withdrawals to continue, which might be why it so terrified the (largely bank-owned) advice industry.

Days before Christmas 2013 the Coalition outlined amendments it hoped to get through parliament. Fee disclosure statements were only to be provided to new clients. Old ones could remain in the dark. And there would be no need for clients to opt in to having money removed from their accounts, ever. And there would no longer be an overarching requirement for advisers to act in the best interests of their clients, merely steps they would have to follow, so that advisers can be certain they have satisfied their obligations.

As July 1 2014 approached and it looked as if the amendments wouldnt get through parliament, Finance Minister Mathias Cormann gazetted regulations that purported to have the same effect. Parliament would have been able to disallow them when it next met, but he delayed tabling them until the last possible moment, lengthening the period of time they were in force without being tested. Then Labor trumped him by reading them out aloud in the Senate, which effectively tabled them and forced a vote. Cormann managed to get the Palmer United Party on side and keep the regulations at first, until Jackie Lambie split with Clive Palmer over the issue and left his party and voted them down.

Then, when all had been lost, the banks and financial advisers begged for more time. They have been “thrown into disarray” and wouldnt have their systems ready. ASIC said it wouldnt enforce the law until July 1, 2015, two years after it had been due to begin.

ASIC and Cormann had given the financial advice industry an extra two years in which to charge commissions and escape an overarching requirement to put the clients first.

Even now, all this time later, I cant work out why Cormann tried so hard.

Looking back over the emails we exchanged, I can see that he distinguished between “sales” and advice. He said that financial advice should be commission-free, but that “sales” were different, which is what the banks were arguing.

And advisers should be allowed to limit their advice about just one topic, such as superannuation, without the need to take everything into account and weigh up their client’s best interests (as do doctors and lawyers, who have to put their client’s best interests first regardless).

He said the requirement for clients to opt in to making continuing payments to advisers was “red tape”, and “retrospective”.

Peter, I have honestly tried my best to do the right thing in the public interest, he wrote. I dont expect that any of this will change your mind, but I thought you should know why we are doing what we are doing.

This article was first published in The Canberra Times on the 25th of April, 2018.

Peter Martin is economics editor of The Age.