Political polarisation in the US - Part 1: How real is the problem?

July 25, 2023

_America is our great and powerful friend so it matters a great deal how reliable our firmest strategic partner is. Is the US heading for a degree of political dysfunction that could blow back into its steadfastness as a leading player and an Australian ally in a multipolar Indo-Pacific?

_

Introduction

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

…

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

W B Yeats The Second Coming

And what rough beast slouches toward Washington to be born again? (Beale with apologies to Yeats)

On any measure polarisation - the movement from the centre to the extremes in political life - has reached levels unseen in the US since the 1930s and possibly the 1890s. Populism - pitting the Common Man against the corrupt Elites (and experts) - has soared. Conspiracy theories are running rife. And woke intolerances and emphasis on identity have grown dramatically on the left. Some see a risk of democracy in the US collapsing. Others talk of America dividing into two countries - the Red States and the Blue States which might live within the borders of the US, but share little in common. And there is little agreement on the fundamental drivers of this increasing mutual loathing between Republican identifying voters and those who are Democrat leaning - it turns out that Republicans dislike Democrats even more than vice versa.

Cumulative differences - economic, ethnic, racial, religious, ideological - between groups forming a polity are often the precursor to social struggle ranging from legislative gridlock, through riots to even domestic terrorism or civil war.

Dimensions of polarisation?

Defining polarisation

We can think of polarisation in a number of ways. Performative polarisation is based on actions (eg voting or demonstrating), programmatic polarisation is based on different ideas about public policy (for examples on taxes or gun control), affective polarisation is concerned with attitudes to the other side (would you like your daughter to marry one).

It also matters at what level this polarisation has happened - is it just among the political elites or does it seep through the whole population?

Elite polarisation - The Presidency, Congress and Supreme Court

Polarisation is most apparent at the elite level of politics and among political activists. Presidential candidates now openly characterise their opponents in terms like crooked, or a basket of deplorables or propose criminal investigations. The rhetoric, particularly with the rise of Trump, has increasingly used exaggerated claims and violent metaphors amped up by media previously undreamed of. The attempted impeachment of Presidential office holders has become almost routine.

With the division of powers in the US, Congressional partisan gridlock has hampered the delivery of successive Presidential programs.

This can be measured by examining the voting patterns of members of Congress.

Voting Patterns of Members of Congress 1949-2011 Republicans Red, Democrats Blue

Network Propaganda, Yochai Benkler et. al., Oxford University Press, 2018.

The picture is clear. There has been a steady reduction in voting across the aisle since the 1960s with the differences becoming sharper and sharper in the 21st century. When the party opposed to the President commands a majority in either the House or the Senate this spells trouble for the Presidents legislative program and nominations.

Increasingly politically motivated timing of retirements and partisan appointments of judges have equally seen the Supreme Court of the United States split between Justices nominated by Democrat and Republican Presidents. The radical decisions by the conservative majority in the current Court in relation to affirmative action in education, abortion, gun controls and the Voting Rights Act are examples. Each saw the Court split on lines reflecting the Presidents who had nominated the respective Justices and reversing long standing interpretations of the Constitution. They have far reaching implications, notably reducing Presidential power and increasing that of State Governors, legislators and courts.

The impact will be felt at the national level. Since the Supreme Court found parts of the Federal civil rights era Voting Rights Act unconstitutional in 2013 a significant number of Republican states have tightened eligibility to vote in a way that will disproportionately impact minority communities and likely reduce the Democratic vote in future Presidential and Congressional elections.

Mass polarisation

When polarisation first became a matter of concern in the 1990s surveys showed that while elite polarisation was firmly entrenched, at the level of registered voters there was still considerable overlap, particularly in relation to policy issues. That overlap has reduced markedly.

By 2017 the median Republican voter shared political values with only 5% of Democrat voters and vice versa. While in 1994 the area of shared political values was larger than the extremes, the reverse was true in 2017, and there is nothing to suggest that this polarisation has diminished in the years since.

Affective polarisation

Voters can have different political values but still acknowledge the legitimacy of the views of their opponents. Political differentiation does not necessarily reflect in social separation. But it seems that this tolerance of diversity in political views has reduced markedly. Pernicious polarisation happens when political identity becomes a social identity.

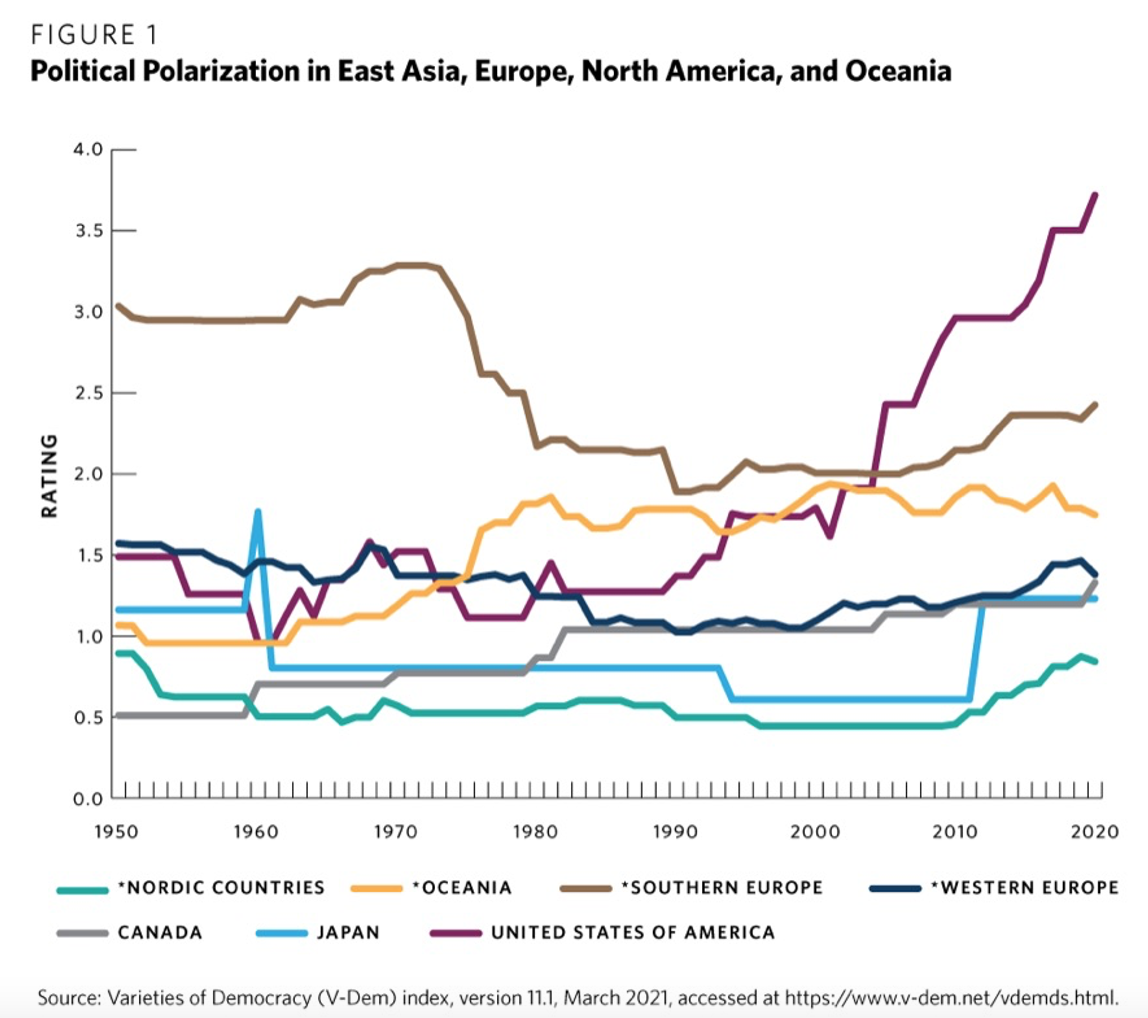

Among the advanced economies the US has seen a sharper rise in affective polarisation than any other democracy (CROSS-COUNTRY TRENDS IN AFFECTIVE POLARISATION Levi Boxell Matthew Gentzkow and Jesse M. Shapiro NBER 2021) since the 1980s. Boxell et al found In five other countries Switzerland, France, Denmark, Canada, and New Zealandpolarisation also rose, but to a lesser extent. In six other countriesJapan, Australia, Britain, Norway, Sweden, and (West) Germanypolarisation fell.

The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has put it like this:

Polarisation in the United States, by contrast, has risen consistently since 1990 and has been at pernicious levels since 2015. The polarisation of U.S. politics is more akin to the experiences of younger, less wealthy, and severely divided democracies and electoral autocracies than to those of its more consolidated democratic peers. (Reducing Pernicious Polarisation: A Comparative Historical Analysis of Depolarisation McCoy, Press, Somer, Tuncel)

Conclusion

There is no doubt that polarisation between Democrats and Republicans is real and increasing. Not since the 1930s has there been such a bitter divide. Pernicious polarisation has reached levels unseen in democracies in Europe, Asia, Oceania or in Canada since World War 2. This is already having consequences for the governability of America, its social cohesion and its ability sustainably to deliver Presidential programs. But the impacts dont stop there - they also affect the attitudes of allies and competitors and influence views of the value of democracy versus strongman autocracy.

View all the articles of this five part series.