EMIRZA ADI SYAILENDRA. Indonesia’s elite divided on China

April 28, 2018

The diffuse nature of policymaking in Indonesia discourages its leaders from departing from the country’s status quo policy towards Beijing. The status quo aims to allow Jakarta to have its cake and eat it too — that is, enjoy close relations with Beijing while preserving its strategic autonomy in ASEAN.

Indonesia’s ‘ non-balancing act’ policy towards Beijing usually involves close engagement with China for pragmatic benefits and to avoid a direct challenge to Chinese policy. At the same time, Indonesia continues to try and expand its policy options. How has this played out?

Jakarta occasionally adopts a ‘ muscle-flexing’ approach involving military displays to signal Indonesia’s strategic independence from China. It also gives outside actors reasons to help deter China and side with Indonesia in the event of a dispute — for example, Indonesia encourages foreign companies to explore the Natuna islands, which are supposed to hold one of the world’s largest reserves of untapped gas and are abundant in crude oil, marine life and potential fisheries.

A recent example of Jakarta’s half-measure policy towards China was when Indonesia announced its decision to rename part of the South China Sea as the North Natuna Sea in July 2017. This came in the aftermath of repeated encroachments on the Natuna islands exclusive economic zone (EEZ) by China and the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s 2016 ruling on the South China Sea dispute between China and the Philippines, which found that none of the features in the contested Spratly Islands generates an EEZ. This was seen by some in Jakarta as an opportunity to reinforce Indonesia’s sovereignty.

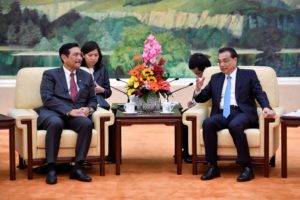

China responded by demanding that Indonesia take back its decision to rename the sea. Indonesia’s Coordinating Minister of Maritime Affairs Luhut Panjaitan took the position that the change was a domestic matter, as it only referred to the part of the sea that lies within Indonesia’s EEZ and not the South China Sea as a whole. This contradicted Panjaitan’s own call in late August 2016 for Indonesia to take a stronger stand on territorial issues with China. Jakarta worries about the possible impact of upsetting Beijing and Panjaitan’s backtracking has created confusion in policymaking circles in Indonesia.

Indonesia has so far neither accepted or formally refused China’s demand. Indonesia still uses the North Natuna Sea name domestically. Submitting to external pressure would be highly unpopular among domestic audiences, particularly leading into an election year in 2019.

Although China has never openly disputed Indonesia’s claim over the Natuna islands, on 19 June 2016 Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua claimed that the Natuna EEZ is part of China’s ‘ traditional fishing grounds’. The Natuna islands potentially overlap with China’s nine-dash line and the Chinese coastguard have made repeated encroachments in the area. There were expectations that Jakarta would assert a stronger policy position towards Beijing to protect its interests in these waters. But Indonesia has failed to do so due to a lack of consensus.

There is a general consensus among the political elite in Indonesia that China poses some kind of threat to the country. But disagreement persists with regards to the nature of the risk and the best way to handle it.

After an illegal fishing incident near the Natuna islands in March 2016, Minister of Marine Resources and Fisheries Susi Pudjiastuti promptly expressed disapproval of China’s action and sought to summon the Chinese ambassador. But some quarters, especially within Indonesia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, are concerned that continuing such an approach might hurt Indonesia’s diplomatic efforts to embrace China and to accept multilateral approaches to conflict resolution. Pudjiastuti appears under pressure to not openly criticise Indonesia’s relationship with China.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs wants to preserve Indonesia’s ‘ honest broker’ role in resolving the territorial disputes through dialogue between China and ASEAN. Some worry that admitting that there is a dispute between Indonesia and China that goes beyond illegal fishing incidents only plays into China’s apparent desire to acknowledge contestation in the Natuna islands.

Others want Indonesia to act strongly against China. After Indonesia’s then-foreign minister Marty Natalegawa reaffirmed in 2014 that Indonesia did not have any territorial disputes with China, General Moeldoko, at the time the commander of the Indonesian National Armed Forces, wrote a commentary in the _Wall Street Journal_revealing a much tougher stance on the issue.

China continues to be a top investor in Indonesia and many, including Indonesian President Joko Widodo (Jokowi), are reluctant to jeopardise the bilateral relationship over territorial issues. Under Jokowi, year-on-year investment from China has grown substantially by 92 per cent. Jokowi has shown some bravado to avoid being perceived as a weak leader, but he has always accompanied this with a series of conciliatory statements.

While Indonesia’s elites continue to be divided on China, Beijing appears increasingly inclined to acknowledge the existence of a conflict between the two countries in the Natuna islands. Indonesia’s ‘non-balancing’ policy is becoming more and more precarious. Indonesia’s elites need to find a way to harmonise their positions on China. Doing so means negotiating from a position of strength, before Beijing’s grip is too strong.

This article was first published in East Asia Forum on the 20th of April, 2018.

Emirza Adi Syailendra is a Senior Analyst with the Indonesia Programme at the S. Rajaratnam of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University.