Chinese geopolitical inroads into central Asia are coming at Russia’s expense

November 23, 2022

At the recent Commonwealth for Independent States (CIS) summit held on October 14 in Astana, Kazakhstan, Tajik President Emomali Rahmon expressed previously inconceivable remarks.

His public admonishment of Russian President Vladimir Putin to treat Central Asian states with more respect showed the growing confidence of Central Asian leaders amid Russia’s embroilment in Ukraine and China’s expanding regional influence.

After coming under Russian imperial rule in the 18th and 19th centuries, five Central Asian states—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan— emerged independent from the Soviet Union in 1991.

While these countries remained heavily dependent on Russia for security, economic, and diplomatic support, China saw an opportunity in their vast resources and potential to facilitate trade across Eurasia. Chinese-backed development and commerce increased after the Soviet collapse and expanded further after the launch of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013.

Billions of dollars in investment, access to Chinese goods, and opening up China’s enormous consumer market allowed Beijing to restructure Central Asian economies. Soviet-era gas pipeline networks, for example, traditionally forced much of the region’s natural resources to flow through Russia to access the European market. The Central Asia-China pipeline and Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline are just some of the newer pipelines built to transport resources to the Chinese market instead.

These developments have added to friction between Central Asian states and Russia. Disputes between Turkmenistan and Russia over gas prices and a mysterious pipeline explosion in 2009 saw Russian gas imports from Turkmenistan decline until they halted completely in 2016, upending Turkmenistan’s access to Europe. Turkmenistan redirected much of its supply to China for the next three years, before a rapprochement with Moscow in 2019 saw imports to Russia resume.

This affair demonstrated the economic opportunities China could provide to Central Asian states that were previously dependent on Russia. Competing Chinese and Russian attempts to supply Central Asia with COVID-19 vaccines was another demonstration of Beijing’s multifaceted approach to increasing its regional influence.

Sensing the inevitability of Chinese investment in revolutionising regional economies, the Kremlin announced the “ Greater Eurasian Partnership” in 2015. This partnership attempted to integrate the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), which Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan are members of, with the BRI. Though this partnership has only been partially successful, Putin has sought to use Chinese investment to help develop Russia’s Far East.

Russia’s connections to the remaining Soviet political networks and military power in the region have allowed Moscow to contend with China’s growing economic edge in Central Asia over the last two decades. But the increasing international pressure on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine has suddenly upset the traditional “ division of labor” between Russia and China in Central Asia. Though still a vital partner to Central Asian states, Russia risks losing greater economic and security ground to China in the coming years.

After cross-border trade between the EU and Russia and Belarus was reduced following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, for example, China placed renewed focus on developing the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR), or “Middle Corridor,” of the BRI. Instead of Chinese trade flowing from Russia into Europe, it is increasingly being transported through Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Turkey. The newly built Baku-Tbilisi-Kars (BTK) railway, as well as other projects like the China-Kazakhstan-Uzbekistan (CKU) railway, will further erode Russia’s importance to the BRI.

On September 14, 2022, Chinese President Xi Jinping traveled to Kazakhstan on his first foreign trip since the pandemic began. His destination was symbolic—the BRI was first announced by Xi in Kazakhstan in 2013, and the country has fashioned itself as the “ buckle” of the project.

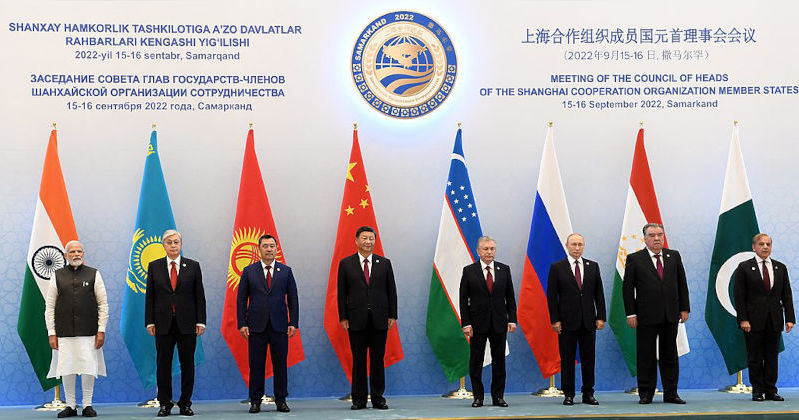

Alongside signing economic deals during his visit in September, Xi vowed to back Kazakhstan “ in the defence of its independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity.” This contrasts with Russian political figures who have questioned the validity of Kazakhstan’s statehood in the past, including Putin. Xi then traveled to Uzbekistan to attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit on September 15 and 16 and signed deals worth $16 billion with Uzbekistan, dwarfing the $4.6 billion signed between Uzbekistan and Russia.

China’s auto industry has also increased its manufacturing presence and share of the market in Central Asia in 2022, as sanctions have hindered Russia’s production capabilities.

China’s growing military presence in Central Asia has similarly been a major concern for the Kremlin. Over the last decade, China has rapidly increased its arms exports to the region. And though China has conducted bilateral military exercises in Central Asia since 2002 in coordination with the SCO, in 2016 China held its first antiterrorism exercises with Tajikistan, and held the “ Cooperation 2019” exercises with Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan, “marking the first time their national guard units had trained with China on counterterrorism.”

In 2021, Tajikistan also approved the construction of a Chinese-funded military base in the country near its border with Afghanistan—though China’s focus on Tajikistan is “ linked more to Afghanistan than to Central Asia as a whole.” However, the use of Chinese private military and security companies (PMSCs) in Africa and the Middle East has also led to concern in Moscow that China’s PMSCs may expand further across Central Asia.

Moscow’s strained military situation became evident in September, when Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, both members of the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) military alliance, engaged in deadly border clashes. While Russia and the CSTO were unable to calm hostilities, the leaders of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan met on the sidelines of the SCO summit on September 16 to cool tensions.

Nonetheless, several factors inhibit China from eclipsing Russia’s geopolitical influence in Central Asia. Beijing has typically been hesitant to commit military forces abroad and continues to see the Russian military as an asset against instability in the region. The Russian-led CSTO intervention in Kazakhstan in January 2022 showed the Kremlin was capable of stabilising vulnerable national governments facing social unrest in the region, as well as cementing their authority and international legitimacy.

Russia also operates a military base in Tajikistan, while Kyrgyzstan hosts a Russian military air base. Kazakhstan’s large ethnic Russian minority, meanwhile, holds local economic and political power, and the Kazakh government remains fearful of a Russian military intervention ostensibly to protect them.

Additionally, Russia retains some economic leverage over Central Asian states. Russia conducts billions of dollars worth of trade with them annually and maintains several Soviet legacy projects that have bound Central Asia to it, such as common gas and oil pipelines, waterways, railway networks, and electricity grids. Central Asian states also have some of the largest annual remittance rates in the world, with the remittances from Russia to Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan accounting for roughly 30 percent of their gross domestic product in 2021.

The Kremlin also has the ability to shape local perceptions of Russia through its dominant media and social media channels in Central Asia. But positive public opinion toward China across the region steadily declined between 2017 and 2021 for a variety of reasons, especially in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. Many Central Asians are concerned over China’s “ debt-trap diplomacy,” while large numbers of Chinese workers brought in to develop BRI projects in the region have resulted in deadly protests and clashes with locals.

Competition between China and Central Asian states over scarce regional water supplies, as well as China’s treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, a Turkic-speaking, largely Muslim ethnic group, who “see themselves as culturally and ethnically close to Central Asian nations,” have also damaged China’s ties in the region.

Evidently, China’s own obstacles and Russia’s lingering presence in the region have helped sustain the geopolitical balance in Central Asia. But mutual pledges by China and Russia to respect one another’s core interests, most recently repeated in June 2022, have contributed the most to preventing greater agitation in the region. While Beijing and Moscow are destined to compete in Central Asia, careful diplomacy will likely prolong their cautious cooperation.

Ultimately, China remains more concerned with Taiwan, the South China Sea, and the broader Asia Pacific region, while Russia is more preoccupied in its eastern and southern regions, most notably Ukraine.

Russia has so far borne the brunt of U.S.-led efforts to contain their foreign policies. But the launch of the U.S.-China trade war in 2018 under former U.S. President Donald Trump marked a serious turn in the U.S.-Chinese relationship, which has continued under President Joe Biden. The Biden administration ( as well as the EU) has criticised and sanctioned China over its policies in Xinjiang, and most recently imposed significant technology export controls on China on October 7.

Heightened tensions with the West will draw China and Russia closer together. While Central Asia is where their interests collide the most, Beijing and Moscow will continue to avoid conflict there to focus on pushing back against Western power elsewhere in the world.

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

First published in COUNTERPUNCH Nov 17, 2022