Australia’s fiscal challenge

September 2, 2023

Productivity growth will be less than projected in the Intergenerational Report, the budget deficits will be worse, and the Government should be setting the scene for raising more revenue.

Last week the Albanese Government released its first Intergenerational Report (IGR) – the sixth in the series.

By definition, the projected future growth of the economy will be the product of three factors - population growth, the participation of that population in the workforce, and the productivity of that workforce.

This projection, however, is not a forecast. Rather it is a conditional projection of what will happen if present policies and other underlying factors continue to operate as in the past or as intended. Such a conditional projection can then help identify future problems and challenges and the likely need for policy changes.

In particular, these IGR Reports have traditionally focused on the potential future budgetary pressures and how these are affected by the projected ageing of the population.

In the latest IGR, however, the Treasurer has sought to broaden the issues considered to cover not only population ageing, but also the implications of and opportunities from:

- the expanded use of digital and data technology,

- climate change and the net zero transformation

- rising demand for care and support services,

- increased geopolitical risk and fragmentation.

How useful are the IGR projections?

The main criticism of the IGR projections has been the allegedly optimistic treatment of climate change. For example, Mike Scrafton, (Pearls & Irritations, August 26) and David Spratt and Ian Dunlop (Pearls & Irritations, August 29) have both argued that the Government’s policies will not achieve the projected reduction in carbon emissions. In addition, Spratt and Dunlop further argue that the Treasury modelling has omitted some of the negative impacts of climate change, such as “health impacts, biodiversity loss, storm surge and sea level rise, amongst many others”. Consequently, these critics think the IGR’s economic projections cannot be trusted.

On the other hand, the Government says that its policies will achieve the legislated climate goals, and the Government is supported by the Australian Energy Market Operator.

I have nothing useful to add to this debate about the Government’s climate change policies, but I think that the productivity assumption is also unrealistically optimistic, and this too is quite critical to the projected economic growth.

The IGR’s assumed annual rate of productivity increase of 1.2 per cent, while lower than adopted by the previous Government, is still markedly higher than the average annual rate of only 0.5 per cent that Australia achieved over the last ten years between 2012 and 2022.

Economic reforms and increasing productivity.

The one thing we seem to be able to agree on in Australia is that increasing productivity is critical to increasing living standards and helping to pay for government services. Hence there are all sorts of proposals about how to change Australian institutions and laws so as to lift the rate of productivity growth in Australia.

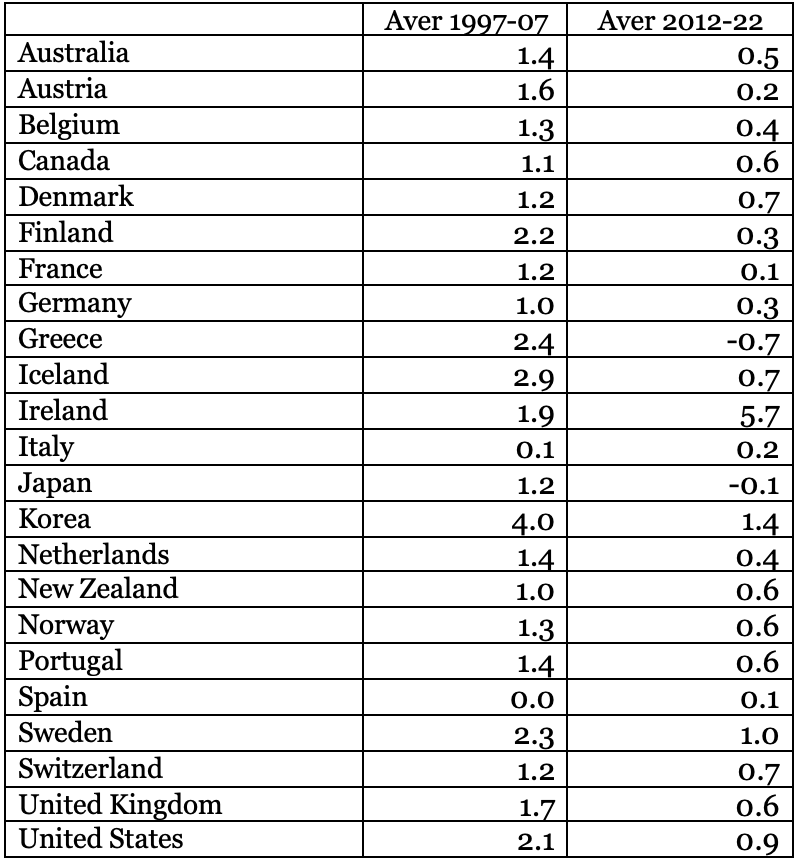

But what the Australian debate has failed to recognise is that the slowdown in productivity growth in the last decade has been a common feature of practically all the advanced economies. Indeed, in almost all these countries their rate of productivity growth in the most recent ten years was less than half their rate of growth in the ten years prior to the GFC (see Table 1).

Table 1: Labour productivity

Average annual percentage changes.

This almost universal slowdown in productivity growth amongst the advanced economies should raise doubts about the effectiveness of many of the proposed reforms to lift the rate of Australian productivity growth.

Instead, the starting point for any reform agenda should be a recognition that through history productivity growth has principally been determined by the rate of technological change, and the fact that productivity growth has slowed in all advanced economies is compelling evidence that the rate of technological change has slowed.

Thus, a reform program should focus on what can be done to increase the rate of innovation and the take-up of new technologies.

The Treasurer has insisted quite rightly that the opportunities from the energy transformation required by the global response to climate change will enhance Australia’s economic growth and productivity. There is also considerable speculation about the productivity improvement from robotics and artificial intelligence.

More broadly, the IGR discusses the productivity potential from the Government’s investment in infrastructure and our education and training systems, encouraging more housing supply, and de-risking supply chains. And the IGR argues that responsive skills and training systems and a well targeted migration program will help the adoption of new technologies and best position Australia to adapt to the consequent future structural changes in the economy.

I would also add that if the Government’s recently announced review of competition policy leads to greater competitive pressures that will encourage businesses to become more innovative and accelerate the take-up of new technologies.

Interestingly, just before the IGR was released, the Business Council (BCA) released an updated version of its proposed reform agenda which supported many of the Government’s proposed reforms. More controversially, however, the BCA also wants a lower rate of company tax and less regulation as key elements of its reform agenda.

Apart from pure self-interest, the BCA is essentially assuming that lower company taxes will lead to higher investment, and by implication that would accelerate the adoption of new technologies. There is, however, little evidence that reducing company tax will make much difference to investment.

As shown in Table 2, in the last ten years business investment in the vast majority of advanced economies increased at a much slower rate than in the pre-Covid decade. But this cannot be explained by any increase in company tax. Indeed, in the US the annual average increase in business investment during the four Trump years was only 2.4 per cent; much lower than in the pre-Covid decade despite the lower company tax rate.

Instead, what matters overwhelmingly for business investment is the rate of increase in demand for a business’s products and its rate of capacity utilisation. Consumer demand is the largest part of aggregate demand, and the obvious reason for a lower rate of increase in business investment in all advanced economies in the last ten year was that, except for Germany and New Zealand, the rate of increase in consumer demand was lower than in the pre-Covid decade, and in most countries much lower (see Table 2).

Table 2: Business investment and private consumption

Average annual percentage changes

In sum, I agree that the Government’s reform agenda, as outlined in the IGR, should help improve the adoption and adaptation to new technologies, and it is also true that there are some promising new technologies on the horizon. However, there is an issue about how much new technologies can lift productivity in what is now largely a service economy. For example, as the IGR emphasises, there will be a rising demand for care and support services, and these are inevitably labour intensive.

It is therefore an heroic assumption to believe that the Government’s reform agenda will turn the rate of decline in productivity growth around by as much as the IGR assumes. Certainly, Treasury has produced no research to support that assumption.

But if productivity growth is likely to be less than projected in the IGR that makes an already difficult budget outlook even worse, an issue to which we now turn.

The Budget outlook and tax reform

As in all previous IGRs, the rate of economic growth is not expected to match the rate of increase in government expenditures. Total government payments are projected to increase by 3.8 percentage points, from 24.8 to 28.6 percent of GDP in 2062-63, with the five fastest growing payments being health, aged care, the NDIS, interest on government debt, and defence. Also there are good reasons to think that these expenditure projections are conservative, as many government programs are arguably under-funded at present.

On the other hand, tax receipts are assumed to remain a constant percentage of GDP over the medium-term. Consequently, while less of an immediate problem over the next ten years, beyond that, in this latest IGR the underlying budget cash deficit is projected to increase as a percentage of GDP to around 2.6 per cent of GDP by 2062-63. And if as I argue, productivity growth is less, then this projected budget deficit is a significant understatement.

Whatever the projected budget deficit it will be unsustainable. Either expenditures will need to be reined in or, more likely, taxes will need to be increased.

The Coalition has grasped the opportunity to claim that expenditures must be reduced and that higher taxes are always inevitable under a Labor government. But the Coalition is (as usual) silent on what program expenditures can be cut – perhaps Labor should press the Coalition to come clean on this point.

Certainly, the Coalition did not manage to achieve any net savings in its last two years in office. According to their own budget documents, policy decisions by the Coalition Government added a net $130 billion to the budget estimates for the four years from 2021-22 to 2024-25, or extra spending averaging $32.5 billion a year.

Thus, given the difficulty of cutting expenditures and the probable fiscal outlook, a responsible government would be setting the stage for tax reform. Furthermore, the focus of that reform should be on how to raise more revenue and not so much on the taxation mix.

Many, including the BCA, have argued that extra revenue should be raised by increasing the coverage of the GST and its tax rate. Certainly, Australia raises relatively less from the GST than most other countries, but it needs to be remembered that all of Australia’s GST revenue goes to the States, and thus does not help fix the Commonwealth’s budget problem. Of course, that revenue sharing arrangement could be changed, but that would be a pity, as sharing a revenue base creates the same problems for government responsibility that are familiar where expenditures are shared.

In short, it is difficult to see how Australia can continue to ensure the adequate supply of Commonwealth government services and assistance without changes to the income tax regime. The obvious place to start would be a review of the Stage 3 tax cuts, but this review will need to extend further to include changes to various tax concessions, and even after that some increase in income tax rates may also be necessary.

What we need to remember is that even if the necessary extra revenue amounted to as much as another 4 per cent of GDP, Australia would still be a low tax country compared to almost all other similar economies. The exception would be America, but that would only be because of a much larger (and probably unsustainable) American budget deficit.