Here comes the human tsunami...

February 12, 2025

This year, more than 400 million people are in search of new homes, of food, water and family security.

The first ripples of the human tsunami to come are lapping at the world’s shores, with a population larger than Europe’s or North America’s already on the road. The greatest population displacement in world history is under way – but at only a small fraction of its potential.

To this point the wave consists of 281 million voluntary emigrants and 123 million refugees of war, tyranny and famine (of whom 75 million are displaced within their own countries – but may be forced to leave).

However, climate change is imparting fresh momentum to the flood, with the UN IOM (International Organisation for Migration) warning that “future forecasts vary from 25 million to 1 billion environmental migrants by 2050”, in addition to the present flow.

One obvious driver of population displacement is sea level rise. Propelled by record carbon emissions, melting ice-sheets and thermal expansion are forecast to raise the seas by two metres by 2100. This will inundate 1.8 million square kilometres of land, displacing 187 million people globally. The waters will rise much faster thereafter.

In the short term, the most serious population displacement, however, is likely to result from regional collapses in food and water security, especially in the world’s swollen megacities.

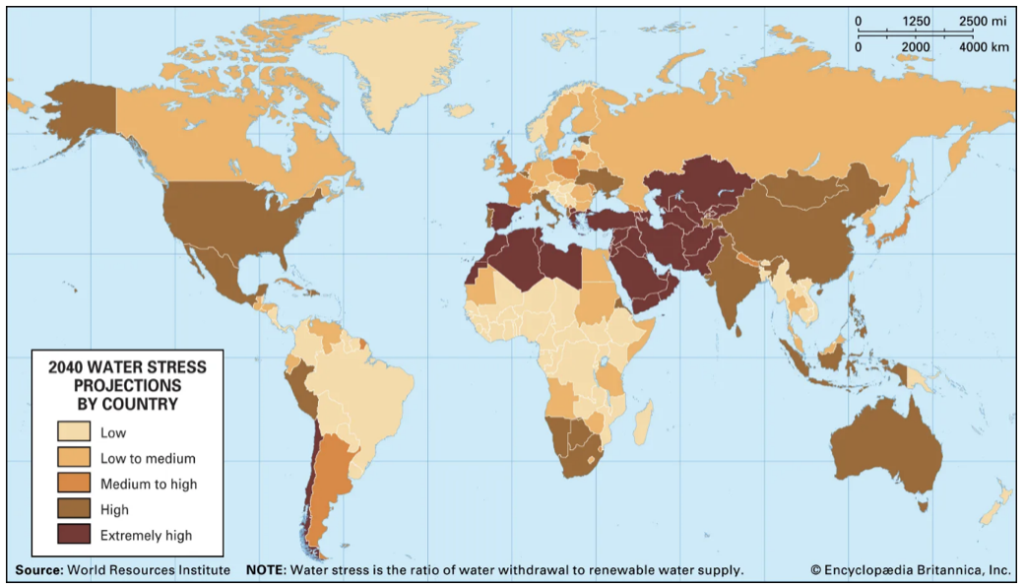

More than half the world’s population (4.8 billion) already faces acute water scarcity for part of the year. Regions such as the Middle East and Central Asia are already effectively out of water, South Asia and north China both face growing lack as groundwater resources run low and there are increasing scarcities in parts of the US, Spain, Chile, Australia, Central America and North Africa.

Since 70% of the world’s water is used to grow more than 40% of our food, water shortages have grave consequences for hunger – and for population displacement. As megacities swell, they are gobbling up farmers’ precious water supplies, undermining their own food security.

Among today’s megacities, Beijing, New Delhi, Los Angeles, Cape Town, Sao Paulo, Moscow, Lahore, Istanbul, Mexico City, Jakarta, Cairo and Tokyo are already running out of water. By 2050, 20 cities, housing one third of the human population, will face acute water scarcity. Population movements will exacerbate this.

Growth in migration has other effects. It has, for instance, already triggered a pandemic of xenophobia, leading to the rise of hard-right and fascist movements and governments around the world, exploiting public fear of foreigners. Even at its present — relatively modest — level, population displacement has already rewritten the geopolitics and local politics of the 21st century, displacing democracy in a nascent wave of tyranny and brutality. This, in turn, is liable to drive emigration from afflicted countries, even those with well-developed economies. Paradoxically, fear of immigrants is thus fuelling growth in immigration.

A largely unseen factor in the growth in migration is the rise of global corporations. As these skip adroitly round the world, seeking to evade tax and business regulation, they suck an increasingly globalised workforce in their wake. This underlines the point that not all the present population flow is from the South to the North. Quite a lot of it is between first world nations, with young people driven by lack of local opportunity to move countries.

A hidden, but clearly growing, element is the quest for “lifeboat” countries by affluent citizens, including many billionaires and corporates, seeking refuges least likely to be affected by a foreshadowed collapse in global civilisation – a concept popularised by British scientist James Lovelock. Indeed, much of the present emigration from India and China may be put down to people hoping to avoid what they foresee in their home countries as resources give out.

Historically, the commonest cause of war is the urge of one country to seize the resources — especially the food resources — of another. (Eg. This motivated the expansions of both Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany in the 1930s.) As the world’s food and water security decline, this is liable to result in increased warfare around the globe, Africa being a prime example. Such wars, where drought, famine and tyranny intersect, are liable to spew out ever-larger displaced populations – as has been the case in the last half century.

From these examples, it can be seen that population displacement generates a momentum of its own — leading to ever-larger displacements due to fear, disinformation, tyranny, resource scarcity, bad government and conflict — and that momentum has the capacity to snowball.

So what is the solution? Clearly it starts with damping down would-be population movements by eliminating resource scarcities, reducing the risks of conflict and providing people with the opportunity to stay where they are.

Resource scarcity can be easily addressed by creating a circular world economy in which food and water are constantly recycled, as I have described in ‘Food or War’. By making food renewable and available to all, the risk of conflict is reduced by around two thirds.

Climate impacts are far harder to resolve in the short term – but we already know the answer: get rid of all fossil fuels. Any corporation or country investing in fossil fuels must be seen as promoting global population displacement of catastrophic proportions.

Getting the human population explosion under control would be a big help, especially if it can be (voluntarily) reduced to a level which the Earth itself can sustain – around two billion, according to a consensus of scientists.

All these measures, and more, are available through the Earth System Treaty, a proposed global legal agreement to ensure our future on a habitable planet.

Unless we humans first agree to survive, we probably won’t. And the human tsunami will be the first hard proof of this.