Environment: Building nuclear involves killing more people

March 23, 2025

Building nuclear power plants requires keeping air-polluting coal power going for an extra 25 years and killing 3000-10,000 Australians. Which milk alternatives will reduce your environmental footprint? Australia’s Carbon Credit Units trade for less than a tenth of the social cost of carbon. US Environmental Protection Agency abandons the environment.

Build nuclear, prolong coal, kill people

The Coalition’s nuclear energy plans are widely considered to be an inappropriate response to Australia’s greenhouse gas problem: too expensive, too slow, too risky, too little expertise and not necessary when there are better alternatives. On top of which, the plans require us to keep our coal-fired power stations going for an extra 25 years until the nuclear plants become fully operational.

The Climate and Health Alliance has analysed the harm that the air pollution generated by burning all that extra coal will do to Australia’s health: 3000-10,000 extra premature deaths, 3500-9,800 extra premature births and low birthweight deliveries, and 14,000-214,000 extra asthma attacks in people under 20. All extra. All unnecessary.

The graph below compares the deaths between now and 2050 attributable to air pollution from coal-fired power under the Australian Energy Market Operator’s (no nuclear) decarbonisation plan and the Coalition’s unclear nuclear plan.

Milks’ environmental footprints

So, you’ve gone vegetarian, you walk, ride a bike and use public transport (except when you drive your EV), you march with Bob Brown, you don’t drink bottled water, you’ve got solar panels on the roof, you’ve installed a heat pump and planted a few trees, and you give generously to your favourite environmental charities. You even fleetingly considered voting Green – once.

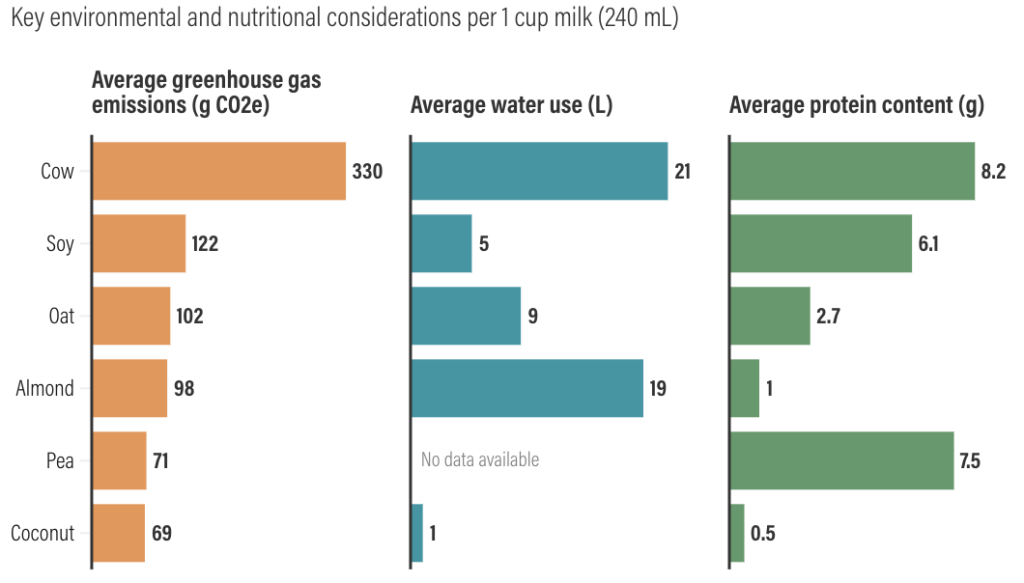

However, while you buy only fair-trade coffee and tea, you do like to put milk in your cuppa. You know that dairy products are associated with enormous greenhouse gas emissions and that claims by milk producers that they are “net zero” and that their milk is “carbon neutral” are probably dodgy at best. So, you’d like to find an acceptable alternative but which milk is best for the environment (and your protein intake)?

Cow’s milk (shouldn’t it be cows’ milk?) is clearly the least environmentally friendly but provides lots of protein (not that many people I know are obviously protein-deficient). Pea milk (a new one on me) scores well on the environment and protein content, and so may be the milk of choice if you are concerned about both. If you aren’t bothered about your protein intake, oat and coconut milks look like good options. Almond milk scores badly on water use.

Cow’s milk also has animal welfare concerns, of course.

Your choice but I feel obliged to fess up that although I don’t eat mammals or birds, I still drink cow’s milk. It’s a work in progress.

How to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions

If a government were truly committed to eliminating all the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions, how could it do it? Seems to me that there are four generic options:

- Educate: tell everyone the facts about the many harms done by GHGs and how to stop emitting GHGs into the atmosphere and expect everyone to do the right thing and stop creating GHGs. On its own, this approach to behaviour change hardly ever, maybe never, works at the societal level for a whole host of reasons. Think diet, gambling, alcohol.

- Legislate: make it illegal to put any GHGs into the atmosphere and fine (or jail) any individual or organisation that breaks the law. This can push illegal activities underground rather than stop them and may not be good for social cohesion. But it can work: most of us wear seat-belts, don’t smoke in restaurants and like having fewer intoxicated drivers on the road.

- Tax: charge individuals and companies for each tonne of GHG they put into the atmosphere, and do it at a level that hurts. Taxing a behaviour the government wants to reduce or stop can be unpopular but has had many successes (cigarette smoking is a great example) and the revenue raised can be used to fund more popular policies.

- The market: set a rapidly reducing annual limit to the total national GHG emissions and introduce an emissions trading scheme for companies to buy and sell permits, each one of which allows the possessor to produce, say, one tonne of GHG. The ETSs that governments have introduced are always immensely more complicated than this, with many caveats, exceptions and loopholes that undermine the scheme’s effectiveness, but this is not the place to explore all of that.

Actually, there’s a fifth option which, as luck would have it, is the one most governments are pursuing at present. That is, do as little as possible, let GHG emissions keep increasing, let global warming and climate change continue to increase, and hope that the inevitable global collapse of industrial societies doesn’t happen until someone else is in charge. When that occurs, the clock would have turned back 250 years and anthropogenic GHG emissions would have returned to almost zero. Success! No matter what people say in surveys, this option has many supporters among the masses, although history’s judgment may look at things differently.

Social cost of carbon

The previous diatribe was really just an introduction to the idea of the social cost of carbon. This is a somewhat complex issue, but in essence it revolves around (1) the idea that producers and/or consumers of products involving the emission of greenhouse gases should pay for the economic, environmental and social damage done by those emissions, and (2) the question of the appropriate level of taxation imposed on each tonne of GHG pumped into the atmosphere (or the appropriate trading price for a permit to produce one tonne of GHG) to cover the cost of the damages caused by the emissions generated by the commodity’s production, use and disposal.

The damages included in the calculations should be those occurring during the whole time each tonne of GHG is in the atmosphere, regardless of where that damage occurs and who ends up paying the associated costs – what economists refer to as externalities, i.e., costs created but not borne by the responsible organisation. The damages might relate to, for instance, human health, agriculture, housing, employment, the environment, industry and infrastructure such as bridges and power networks. The costs might be borne by individuals, communities, social organisations, other companies or governments. This is the social cost of carbon (SCC).

The SCC matters because, to quote the UK Government, “… it signals what society should, in theory, be willing to pay now to avoid the future damage caused by incremental carbon emissions”. Note the “in theory”. In practice, most of society shows little interest in the problems we are creating for those who come after us.

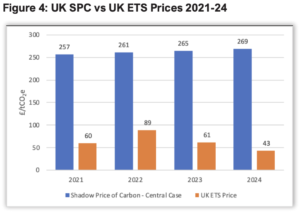

Now it just so happens that the UK has an Emissions Trading Scheme and the government has estimated the SCC so that it can set a Shadow Price of Carbon for costing policy options. The graph below compares the SCC (or SPC in the graph) with the actual price that the UK’s ETS certificates were trading at during each year from 2021-2024.

Two things stand out:

- The ETS price for each tonne of GHG is considerably lower than the cost of the damage done by that tonne of GHG (the full social cost of carbon). In fact, over the four years, the ETS price averaged just 24% of the SCC/SPC.

- Annual changes in the ETS price bear no relationship to changes in the SCC/SPC, which inevitably keep increasing.

While these figures relate to the UK rather than Australia, there’s no reason to assume that the SPC/SCC will be vastly different here. So, were Australia to introduce a meaningful carbon tax or were it to have an effective ETS, the tax/price would need to be around $500-$550 per tonne of GHG.

The nearest Australia has to an ETS is the Australian Carbon Credit Units scheme. During 2024, ACCUs traded for a paltry $30-$40 per tonne – simply a small price of doing business for a big-emitting company rather than a serious impost for the damages done by their company’s products.

Anthropogenic methane emissions

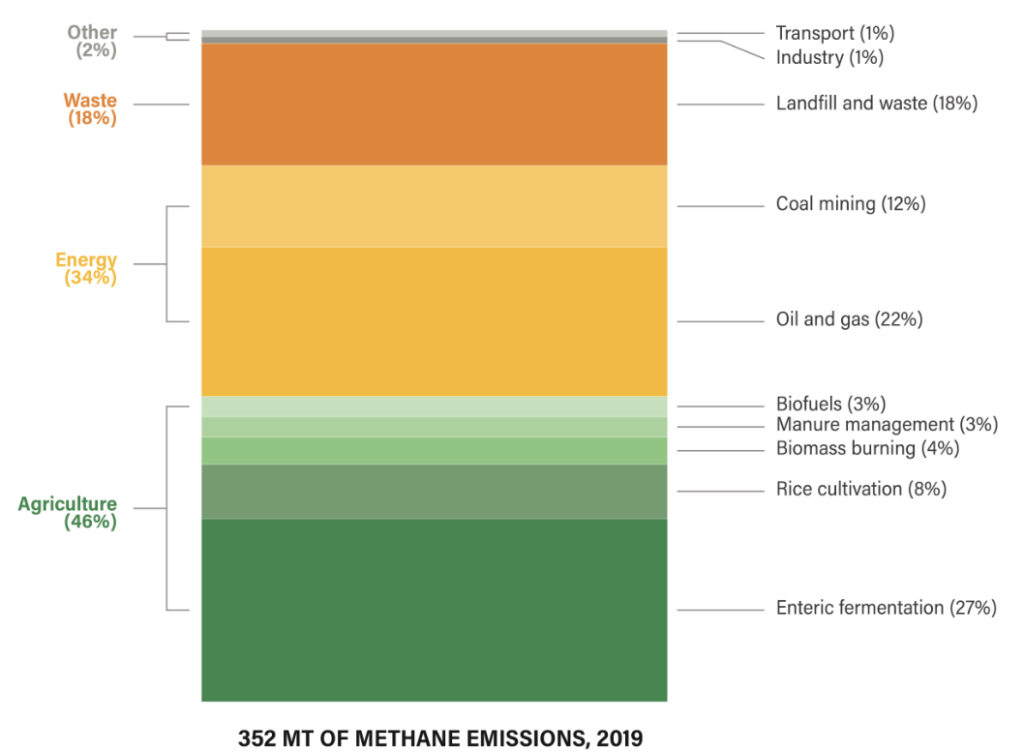

Humans are responsible for approximately 60% of the methane entering the atmosphere each year. The figure below provides a detailed breakdown of the approximately 350 million tonnes (MT) of methane produced by human activities each year.

Over a quarter is produced by ruminants (cattle, sheep and goats) and almost a half originates on farms – note the sizeable contribution from rice farming. More digestible feed, methane-inhibiting feed additives, breeding low methane cows and anti-methane vaccines all have potential for reducing burped methane (we could also eat less meat), while low-methane varieties and letting paddies dry before the next flooding can reduce the methane associated with rice production.

A third of the emissions come from the production and burning of fossil fuels and almost a fifth from waste. Emissions from both can be reduced.

Goodbye Green New Scam. Hello Golden Age of American success

Lee Zeldin is Trump’s new Administrator of the US Environmental Protection Agency. In this edifying two-minute video, he reveals how the “largest deregulatory announcement in US history [will end] the Green New Scam [and] power the Great American Comeback to usher in the Golden Age of American success”. No more suffocating rules… no more Good Neighbour Rule… no more Holy Grail of the climate change religion. Protecting the environment? … didn’t rate a single mention.

Oh no! … he’s even got the ‘“so-called” social cost of carbon in his sights.

Snapshot below of some of Zeldin’s changes (more details here if you really want to know).