Environment: Humans’ contempt for the natural world drives environmental destruction

March 30, 2025

Environmentalists have failed to transform the underlying social values that drive environmental destruction. Fifteen companies produce 30% of Australia’s greenhouse gases. Mountains provide 60% of our fresh water, but not for much longer._

_

Who is really destroying the environment?

Are environmentalists as culpable as governments for failing to protect the environment?

A recent essay by Georgina Woods provides a serious critique of environmentalists’ current goals and ways of working. Has the profusion of professional, relatively well-funded, relatively well-staffed environmental organisations, mostly based in capital cities, undermined vigorous local activism, led to a restricted range of bureaucratic goals that are largely based around regulation and failed to engage the public with the task of achieving the changes required? Has there been inadequate attention on building social solidarity and changing the societal values that drive environmental degradation? Basically, Woods asks, have we set ourselves up to fail? The examples Woods cites are predominantly Australian but her concerns are global.

I have extracted some quotations below to give you a flavour of the arguments Woods advances, but I strongly encourage you to read the whole essay.

“In Australian public life ’the environment’ tends to be regarded as either wholly decorative (look at this adorable animal!) or a radical threat to our way of life (protecting the environment will wreck our economy!).

“Australian environmentalism is not offering a shared account of its role in society and the nature of the change it seeks. At times, the work appears to be about the preservation of islands of great beauty or diversity, discrete locations separate from society, places to visit. Otherwise, perhaps ‘sustainability’, tweaking the rules of exploitation such that it can carry on indefinitely. Missing from both of these is a necessary conceptual leap to radically reorient our understanding of the world we inhabit.

“In most cases, to make change, environmentalism has to convince someone else who does have power. The range of tactics available to environmental campaigners reflects these limits.

“The outcomes sought by environmental campaigns have tended to be bureaucratic and regulatory. In the absence of a deeper focus on values, that turns out to have been a grave mistake. We have sought to develop relationships with people who wield power and win them over, or to conduct outreach and communications campaigns that ‘make the environment an election issue’ but have failed to transform the underlying social values that drive environmental degradation. We have opted, in short, to create ‘green tape’ – gazetting rules and regulations but leaving Australia’s misunderstood and broken relationship with itself unhealed. The technique of ‘campaigning’ is narrowing, directing the focus of attention and political action to a highly specific goal: ban mining on the Reef, make this forest into a National Park, prohibit land clearing.

“Environmental advocates squander what little power we have when we recoil from confronting the illusions and lies at the heart of Australian society.

“Campaigns against the causes of climate change in particular have been wandering in circles because we have shied away from challenging the underlying drivers of environmental exploitation. Climate change cannot be addressed in one election cycle, nor can it be stopped with rules or machines. It is not an environmental ‘issue’. It is a manifestation of a fundamental error that characterises our lives: we are alienated from the ground we walk on and contemptuous of the teeming natural world we inhabit. To be effective, climate change advocacy must bring to the surface the contradictions and fragilities that modernity disguises beneath its shiny surface, its technological and bureaucratic confidence. In Australia, this also means confronting the ongoing process of colonisation, since the two are historically and conceptually linked.

“In any case, a system that values workers, children, rivers, marsupials and coral reefs only as far as they are productive economic units is not a system that should command our loyalty. To the extent that environmental advocates actively participate in upholding the illusions of industrial modernity with enthusiasm for renewable energy giantism, private electric cars and accelerated development, they become, in Milan Kundera’s words, ’the brilliant allies of their gravediggers’.”’

The law is a powerful tool for environmental protection, probably the best one we’ve got. But the law depends on the lawmakers and most of our current Australian parliamentarians don’t genuinely care about the environment. Woods reminds us that we need to elect MPs who are already committed to environmental protection and sustainability. That will not occur until people value and vote for the environment and a stable, healthy climate. The environmental movement’s current strategies and methods of operation, Woods suggests, are failing to make this happen.

Who emits the most GHGs in Australia?

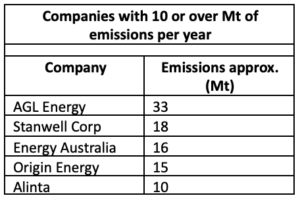

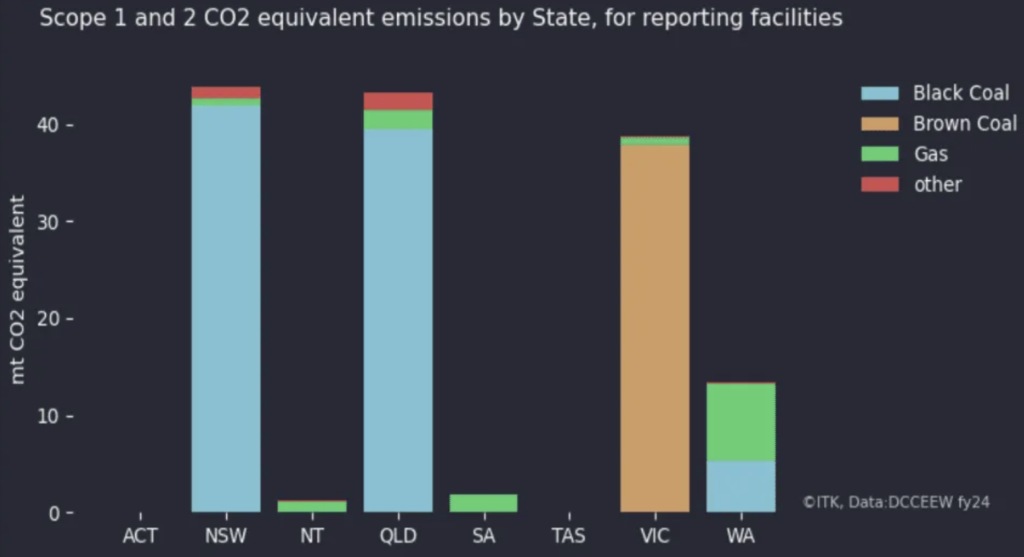

Fifteen Australian companies are responsible for producing 132 million tonnes (Mt) of CO2 equivalent emissions per year. That’s just under 30% of Australia’s total greenhouse gas emissions. Who are these companies? Which are their dirty facilities and where are they located?

Let’s start with the companies (table below). Five produce more than 10Mt of emissions per year. AGL is way out in front despite the closure of their Liddell power station in the Hunter Valley two years ago. AGL alone produces about 7% of all Australia’s emissions but, to be fair, they do produce by far the most electricity in Australia. Collectively, the top five companies produce 20% of all GHGs. Five more companies each generate 5-10Mt of emissions per year, totalling about 33Mt.

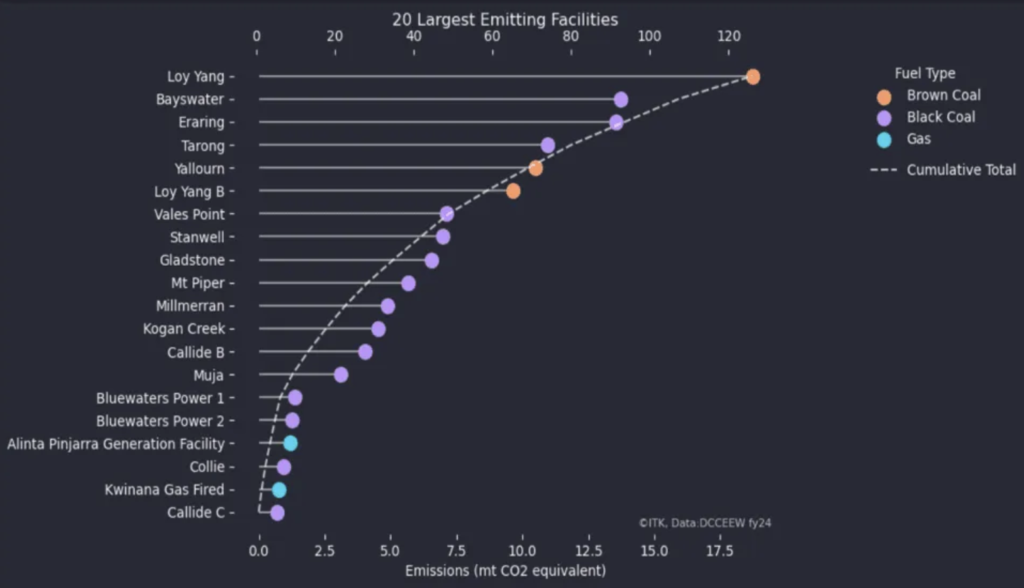

Next, which are the high emitting facilities? The graph below displays the individual emissions of 20 electricity generating facilities (bottom axis) and their cumulative emissions (dotted line and top axis). While all emissions are significant, it’s clear that the cumulative emissions of the top three facilities are about the same as those of the bottom 14. No surprise to see that the remaining brown coal power stations are all very dirty.

Finally, where are all these high emitting facilities located? The figure below speaks for itself.

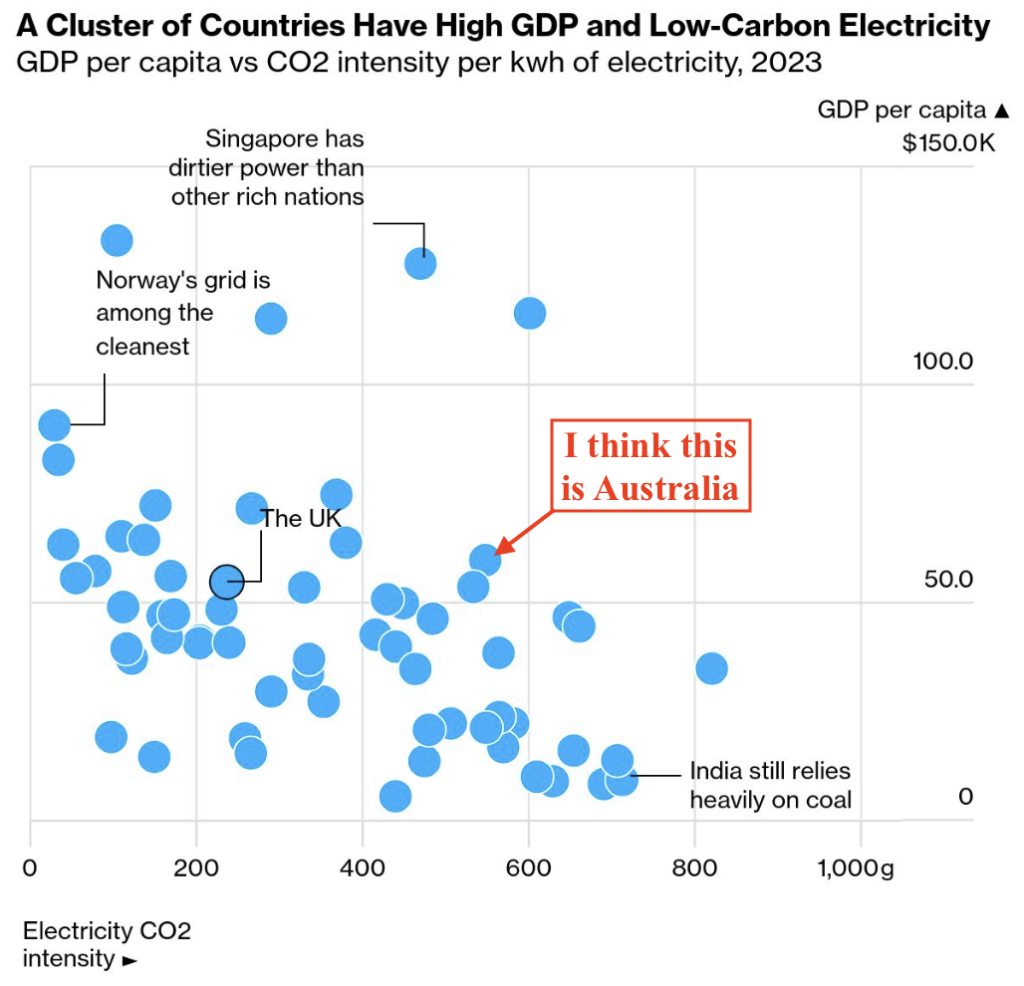

Sure, there are plenty of good reasons for all of us to do whatever we can to reduce our own emissions, but the major problem that needs sorting is how we produce our electricity, not how we use it. The scatter plot below (from the Bloomberg Green e-newsletter on 15 March) plots the wealth of a range of countries (in GDP per person) against the amount of CO2 they produce in generating their electricity (grams of CO2 per Kilowatt hour). Australia’s power system produces at least 10 times as much CO2 per unit of electricity as the cleanest systems and compared with similarly wealthy countries (around US$60,000 per person) generates the most emissions.

Winter wonderland

Olympic Cold Medal for anyone who knows what this machine is called, what it does, why it’s needed and what it’s got to do with climate change.

World’s water towers draining away

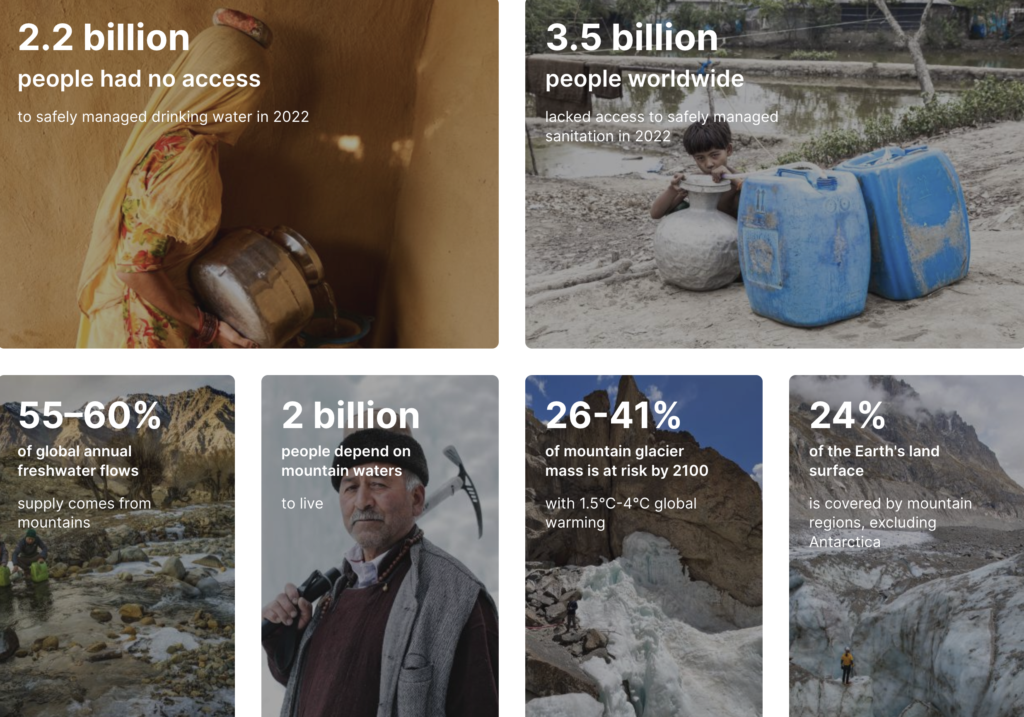

Flushing the toilet is one of the greatest conveniences in my life. I frequently reflect on how lucky I am to live in a country with an efficient system for removing household sewage (although its subsequent management could be improved in some Australian municipalities). Sadly, however, more than 40% of the world’s population lack access to safely managed sanitation.

According to a recent UNESCO report, over a quarter of the world’s population also lives without access to safe drinking water. Twenty-five countries, home to a quarter of the world’s population, face “extremely high” water stress every year, and half of the world’s population experiences severe water scarcity for at least part to the year.

Although safe, reliable freshwater and sanitation are crucial for everyday life, domestic/municipal functions account for only 13% of global freshwater use, about the same as industry (15%, but more in high-income countries). The big drinker is agriculture at 72%, more in low-income countries. Freshwater usage is increasing at 0.7% per year, quickest in rapidly developing countries. Interestingly, increasing population numbers are not a major driver.

Mountainous regions provide about 60% of the world’s freshwater. The “water towers” of the world are vital sources of freshwater for the lives and livelihoods of billions of people living in the mountains and downstream – for toilets, taps, food, mining, forestry, hydroelectric energy production, tourism, etc. And for the survival of sensitive mountain ecosystems as well as those downstream.

But the mountains are experiencing two to three times the average global warming and this is causing a shift from snowfall to rainfall, decreased snow cover, rapid melting of mountain glaciers (glaciers on Mounts Kenya and Kilimanjaro will be gone by 2040), thawing of permafrost and more extreme rainfall events. These lead to more erratic water flows off the mountains with consequent floods, landslides, droughts, increased sediment loads in the rivers and rising sea levels.

With global warming likely to be in the 1.5-4.0oC range by the end of the century, mountain glaciers will lose 26%-41% of their mass by 2100 compared with 2015, at which time they had already been melting for several decades. No wonder that 2025 is the International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation.

National boundaries rarely coincide with the edges of mountain ranges and river basins, making trans-boundary solutions to freshwater problems both more difficult and more essential. According to UNESCO, the solutions are the same as for other environmental problems: better information systems to monitor the changing environments and inform policy; involvement of local populations, especially indigenous groups and women; technical capacity building; better governance of water systems; and, what a surprise, money. But, hang in with me on this one, I know it’s a crazy idea but… what if we were to find out what’s causing global warming and try to do something about it? Do you think that might be possible?

As the report says, “Nothing that happens in the mountains stays in the mountains. In one way or another, we all live downstream.”

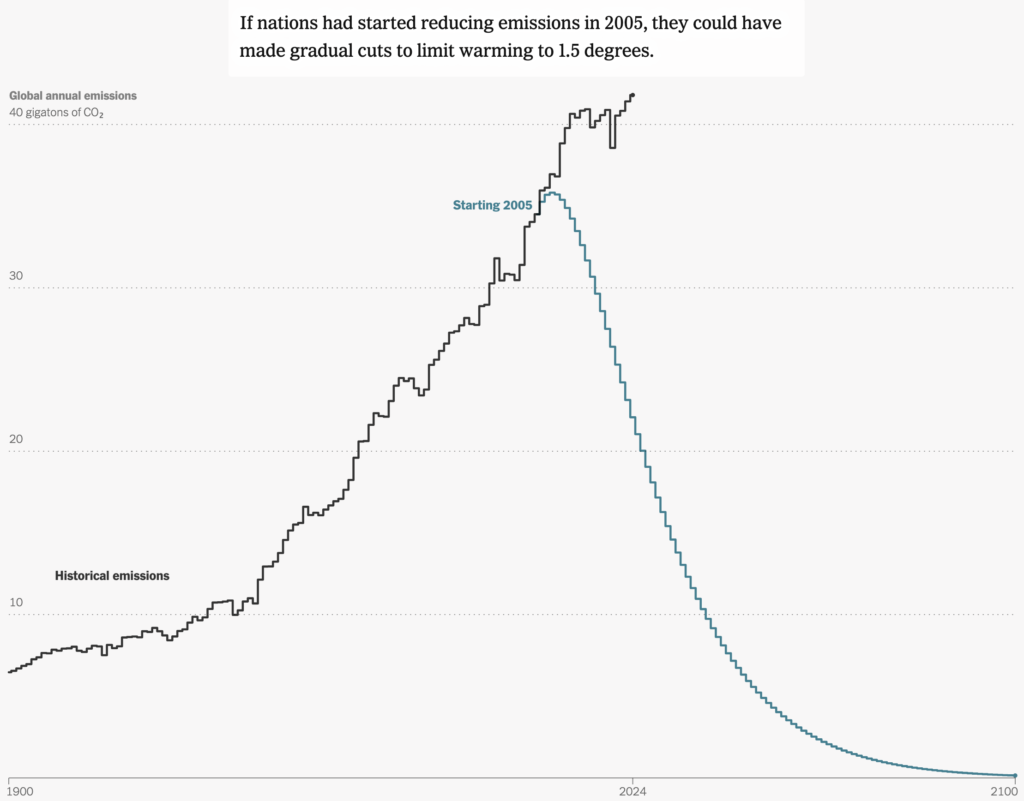

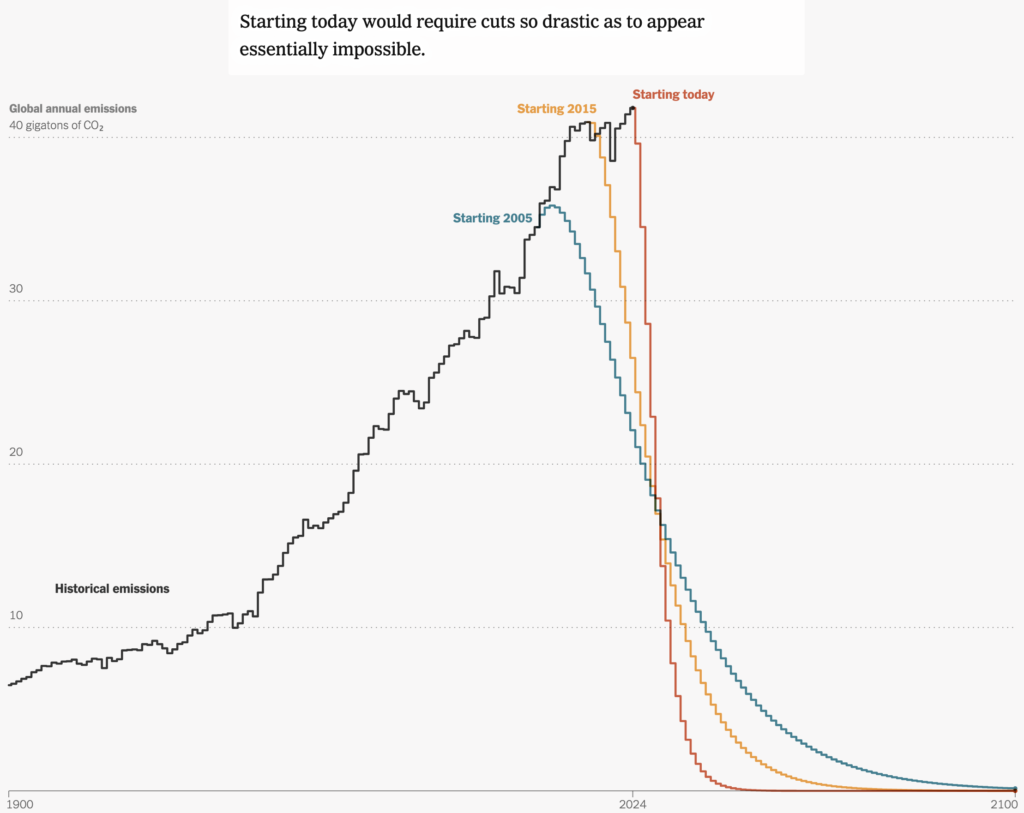

We had the choice of slow and steady …

… but we chose not at all until it was too late.

Just imagine how easy it have been if we’d started in the early 1990s when governments realised the problem and started talking about solving it.