Environment: The folly of focusing on net zero

March 16, 2025

Governments and corporations have been tricking the public by focusing emissions reduction attention on net, rather than real, zero. Reducing methane emissions would reduce global warming quickly and cheaply. Bring back our swamps.

Climate bureaucracy salad

You are perhaps aware that Australia has a Climate Change Authority (CCA) if only because our federal Labor Government boldly appointed Matt Keen, ex-NSW Liberal treasurer and environment minister, as its chair last year. The CCA’s role is to “provide expert advice to the Australian Government on climate change policy”.

But did you know that we also have a Net Zero Economy Authority? No, neither did I, but we do. It was established by the government in December 2024. The Authority is “central to the government’s vision for a _Future Made In Australia_ [and] promotes a just net zero economic transition for Australia, its regions, industries, workers and communities”.

And did you know that the Australian Government is developing a Net Zero Plan that “will lay out and extend Australia’s action on climate change [and] guide our transition to the legislated target of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050?” Again, me neither.

Finely dice the alphabet. Arrange small collections of the cubes into catchy sequences – a mix of upper- and lower-case characters provides interest. Season with vinaigrette bureaucratie and present on a bed of inertia leaves. Sprinkle with a fines herbes mix of hypocrisy and obfuscation, both thrive in Canberra all year round. Serve with crusty pain de bullshit. And there you have it, my soothing climate bureaucracy salad – enjoy. Serves millions. (Can be stored indefinitely on the shelf for re-use but beware, it’s likely to be binned by a new head chef.)

Net zero is not a climate hero

Anyway, enough of the federal government’s climate bureaucracy, what is really interesting are the repeated references to net zero and the NZEA’s definition of net zero:

“Net zero means balancing the amount of greenhouse gas emissions that go into — and are removed from — the atmosphere. It simply means we stop adding to the problem of global warming. The goal is to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.’”

Apart from the poor sentence construction, there are several problems with net zero in general and with this definition in particular. For instance:

- When the idea of net zero first appeared in 2018, it was intended for use as a global concept, a goal for all eight billion of us to strive towards. The whole idea of putting the emphasis on reaching net as opposed to real zero emissions is problematic in the first place, but it does have a skerrick of logic to it when applied globally and as intended.

- The flimsy logic focuses attention on two considerations. First, CO2 is removed from the atmosphere through natural processes, for instance by plants, absorption by the oceans and weathering of rocks, as well as being naturally released into it. The two processes have been in rough balance since the last Ice Age. Second, some industries are genuinely difficult to completely decarbonise at present. After they’ve done all they can to reduce their emissions, the residual emissions, so the argument goes, should be balanced in the company’s CO2 ledger by ensuring that they arrange for an additional equivalent amount of CO2 to be absorbed from the atmosphere, for instance by planting more trees or restoring wetlands, thus “offsetting” their residual CO2 emissions.

- The net zero idea and goal was rapidly adopted by many national and sub-national governments and private corporations because it allowed them to keep producing and/or exporting and/or burning fossil fuels while claiming to be fulfilling their responsibilities to limit global warming.

- It was not the original intention for each individual nation, sub-national jurisdiction and company to strive for net zero. It is, however, very convenient for them, which explains its growing popularity in recent years. That popularity is now waning as governments and companies seek to curry favour with Trump but maybe that’s no bad thing as sub-global net-zero goals are counter-productive to the goal of controlling global warming.

- If we have to use net zero, only the hardest to abate industries (e.g., cement, steel, shipping, fertilisers) should be using carbon offsets to balance their residual emissions and reach net zero, and only then in the short to medium term. The fossil fuel industry, whose activities are most responsible for climate change, should most certainly not be offsetting their emissions to keep themselves in business for as long as possible.

- With exceptions for industrially and socially developing nations, individual nations should be progressing rapidly to real zero, not keeping their dirty industries alive by allowing them to offset their CO2 emissions and claim to be progressing towards net zero.

- One problem with a country such as Australia using net zero emissions as its goal is that it completely sidesteps the responsibility we should carry for causing much of the global warming problem over the last 150 or so years. Industrialised, historically high emitters such as Australia should be going well beyond net zero to net negative emissions to allow developing countries some short-term leeway with their emissions that would help them develop economically, industrially and socially.

- Australia’s dereliction of duty in this regard is (inadvertently?) exposed by the sentence, “It simply means we stop adding to the problem of global warming." No mention of reducing or even eliminating the problem, just stop making it worse. And no mention of reducing real emissions.

Ken Russell wrote an excellent critique of net zero in P&I a few weeks ago. As he says, “Carbon offsetting is a poor alternative to stopping emissions at source and its use should be minimised. Disastrously, it is being extensively used in Australia and globally. It defies logic that companies whose core business is extracting fossil fuels, the opposite of decarbonisation, are being allowed to offset emissions. The objective [of phasing out fossil fuels as quickly as possible] appears to have become how to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 without phasing out fossil fuels.”

Our federal government is hoping that their climate bureaucracy salad will either bore the population into disengagement or cause them to confuse busy-ness with actual achievement

The biography of methane

Methane is the second most important greenhouse gas and, like CO2, its concentration in the atmosphere is increasing, having doubled in the last 100 years.

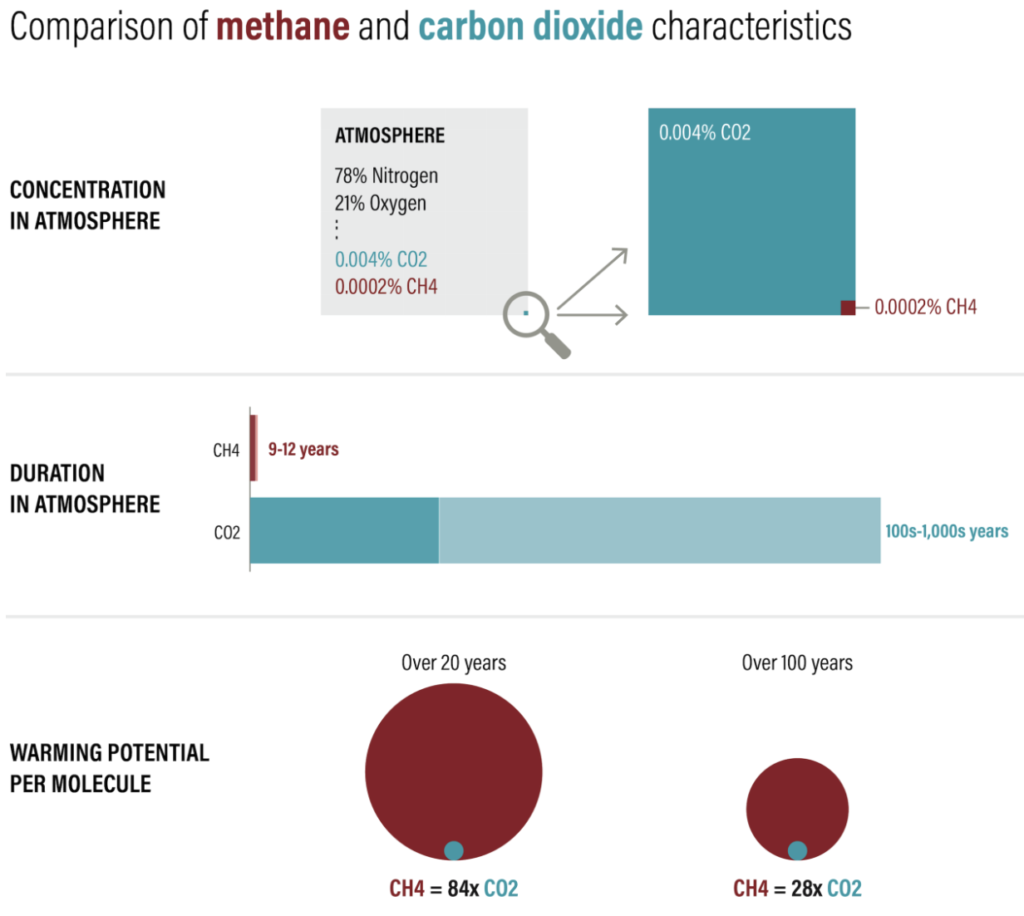

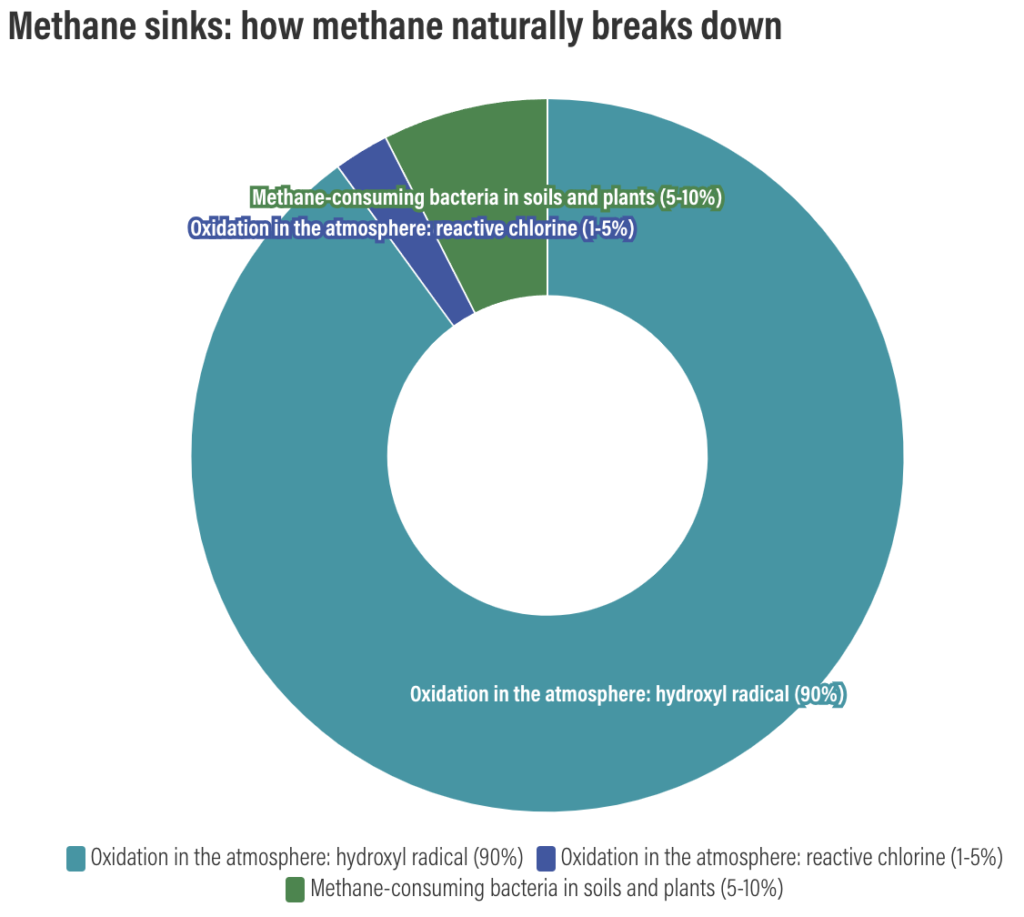

Methane has been responsible for more than a third of the warming we’ve experienced in the last 250 years. This is despite its atmospheric concentration being about a twentieth that of CO2 and its atmospheric life lasting 1-2 decades rather than CO2’s thousands of years. The reason for this is that during those 20 years, methane is 84 times more effective than CO2 at trapping the sun’s energy.

The two figures below provide a brief biography of atmospheric methane.

First, where does it come from? About 40% comes from natural sources, mostly tropical wetlands and freshwater systems and also thawing permafrost in the Arctic. The remaining 60% is created by human activities such as agriculture, waste disposal and the fossil fuel industry. As these activities increase, so do methane emissions. But the global warming that human activities are causing is also increasing the methane emissions from natural sources.

Australians love to think that the country punches above its weight in many domains. Unfortunately, nowhere is that more true than with our methane emissions to which our coal, gas and agricultural export industries make large contributions.

Second, why does methane disappear so quickly from the atmosphere? Without going into all the chemical details, natural processes in the atmosphere oxidise most of the methane (CH4) into CO2 and water (H2O). Bacteria in soils and plants also break down a little methane.

So, what should we be doing globally about our methane problem? Ideally, we would reduce the anthropogenic sources of atmospheric methane as quickly as possible. This would have an immediate beneficial effect on global warming and is eminently doable using currently available technologies at a modest cost, maybe even a cost saving. Unfortunately, as with CO2, the companies and governments responsible for methane talk about reducing emissions and sign agreements, but don’t do much to make it happen, as evidenced by the continuing increase in emissions.

This has led some scientists to talk about removing methane from the atmosphere – again, just like CO2. This is such pie in the sky at present that I can’t be bothered to discuss it, but if you are really interested the link above provides some details.

Restoring Australia’s swamps

It’s no secret that I’m a big fan of swamps, bogs, marshes and peatlands. They look good, they teem with a vast array of wildlife, they filter and regulate water flows and they absorb and store vast amounts of carbon. Unfortunately, most of the swamps and other wetlands in Australia and worldwide have been drained in recent centuries for agriculture and urban development.

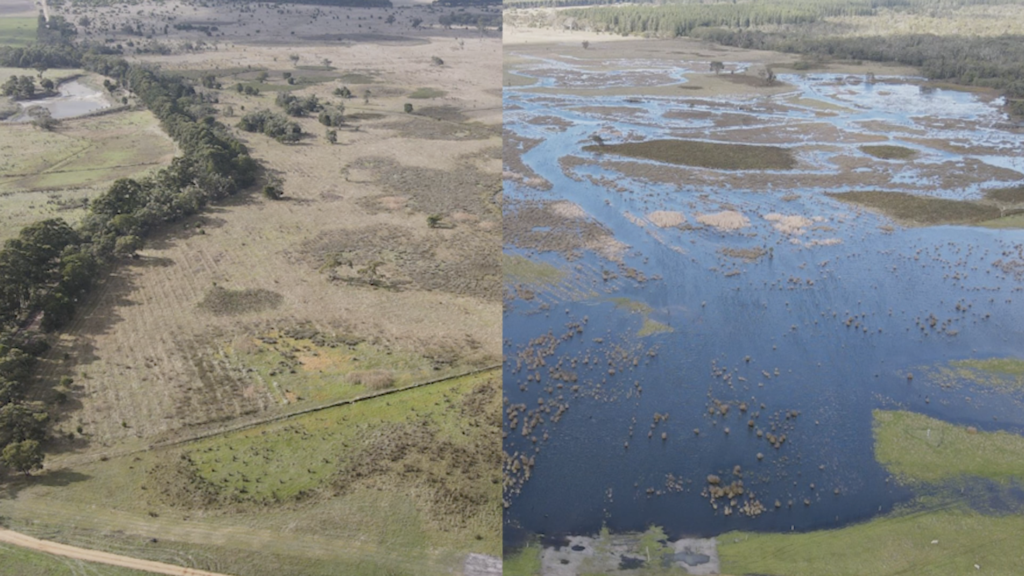

This three-minute video from Nature Glenelg Trust is really a fundraiser for the restoration of Wirey Swamp about 30km northeast of Mount Gambier. My purpose in bringing it to your attention, though, is to let you see the enormous improvements that have already occurred about 90km west in South Australia at Mount Burr Swamp. After the artificial drainage channels were blocked, the area’s water holding capacity was restored and the swamp was re-established.

For another example, watch this three-minute video about saltmarsh restoration on the north coast of NSW.

Image: Supplied - Saltmarsh on the north coast of NSW