Federal-state politics: Western Australia’s election – why we need proportional representation

March 21, 2025

Because what is bad for the Coalition is usually good for Australia, Labor’s thumping win in Western Australia must be seen as a good outcome, but it points to a problem in our system of representative democracy. Democracies shouldn’t produce winner-take-all outcomes.

Political parties tend to assess elections on the basis of seats won or lost, and on that criterion it was a disaster for the Liberals, whose representation has risen from two to seven seats while their National colleagues (not a coalition) have gone from three to six seats in the 59-seat chamber. [1] These are outcomes people like Putin and Lukashenko would literally kill for.

You can see the outcomes on the ABC site and on William Bowe’s Poll Bludger: because their models are different their projections are a little different, but they will converge as votes are counted.

There was a heavy swing against Labor, of 18% in primary votes, or 12% in TPP terms, bringing its TPP outcome down to 58:42. The Coalition will focus on the swing, and will point out that the Liberals did comparatively well in outer suburbs (while re-capturing only two seats, Nedlands and Churchlands, of their old “heartland”). A statistician would see the swing as a convergence back towards the centre rather than as a significant shift in voter support.

Rural ABC reporters suggest that “regional” (i.e. outside Perth) voters in particular have turned on the Cook government, but there is no evidence to support that claim. The rural and urban swings have been much the same. [2]

A group of three political scientists from Murdoch University have a Conversation contribution interpreting the results from a state perspective, while Adrian Beaumont, also writing in The Conversation believes that apart from giving federal Labor a morale boost, it does not have many implications for the federal election, but there may be some that are worth exploring.

Federal implications – At least three seats could be tightly contested

One reason Western Australia has particular salience federally is that on election night its voting closes two hours later than on the east coast, adding to the theatrical tension when the count is close, as happened in 2022.

Of the 15 Western Australia seats contested in 2022, three are on margins less than 3%:

- Curtin (51:49), a prosperous electorate between the city and the beaches, won from the Liberals by independent Kate Chaney;

- Moore (51:49), an urban coastal strip, north of the Curtin electorate, won for the Liberals by Ian Goodenough. Having lost the pre-selection for the 2025 election, Goodenough will be standing as an independent.

- Tangey (52:48), an affluent inner-suburban electorate, won from the Liberals by Labor’s Sam Lim on a 12% swing,

Following a redistribution in 2023, there is a new outer-suburban electorate, Bullwinkel. Antony Green, using 2022 federal results, sees little change in the margins experienced by present members, and assigns Bullwinkel to Labor, but he believes it will be very hard for Labor to contest. It very much fits the model of outer-suburban electorates, with many heavily-mortgaged homebuyers, that Dutton is targeting.

Climate 200 lists three community independents who will be contesting the coming federal election. Chaney will re-contest Curtin. Nathan Barton will contest Moore, making for an interesting four-way contest – it could go any way. And Sue Chapman is standing in Forrest, an electorate centred on Margaret River, held by the Liberals’ Nola Marino (54:46).

Writing in Open Forum before the state election — How the west will be won — John Phillimore of Curtin University sees Labor at risk in Tangey and facing a tough battle in Bullwinkel, while Chaney will face a tough battle in Curtin.

In itself, the state election provides only a few clues about the federal election. In the state seats of Cottesloe, Churchlands and Nedlands, the state electorates more or less covering Chaney’s Curtin federal electorate, the Liberals have clawed back support, and have prevailed against a strong independent candidate in Cottesloe. In fact, this is about the only part of metropolitan Perth where they have done well.

In the independents’ favour, however, is a net fall in the two-party vote: Labor’s primary support fell by 18%, but the Liberals picked up only 7%, the rest going to Greens and independents. And almost unnoticed, an independent nearly grabbed the state seat of Fremantle off Labor with a swing of 28%.

Those who focus on two-party outcomes may have missed the fact that while Labor’s primary vote is down by 18%, the Liberals’ gain is only 7%. The Greens and “others” have both enjoyed gains of 3% to 4%

Political recriminations – It’s policy stupid

Recriminations have started, not just for this outcome, but for two successive disasters for the Liberals and Nationals. The Nationals have compared the conservatives’ behaviour over successive elections to that of a drug addict who will not face up to the need for change.

The Liberals will probably change their leader – always a useful scapegoat. Factional struggles will be named as a factor, but which party does not have factions? Candidates, who made incautious comments about abortion, will cop some of the blame. Anything but policy.

But the problem for the conservatives may be more systemic. When in opposition, rather than reviewing their policies and updating them in line with electors’ needs, the Liberals resort to negative campaigns. It works when there are only two parties and politics is a zero-sum game, like a football match. But when there are alternatives — Greens, independents — who may be able to exert political power, the contest is no longer zero-sum: for the main parties the contest becomes lose-lose.

This applies not only in Western Australia: it is a national phenomenon. When voters or journalists ask Coalition politicians why people should vote for them, the answer is almost always “to get rid of Labor”, and the same goes for their backers in partisan media.

A huge majority – Unhealthy for democracy

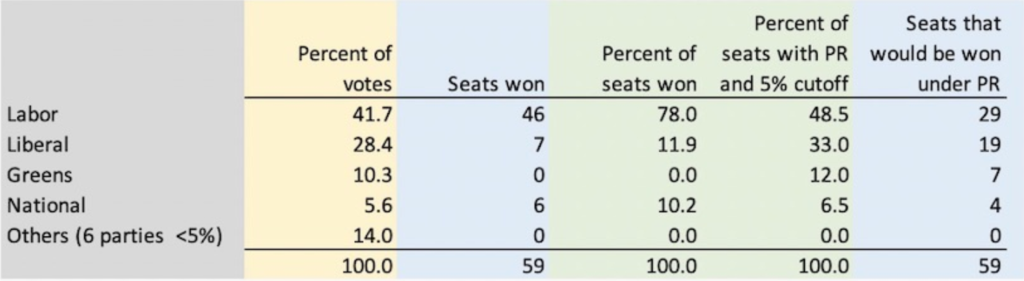

The Cook Government came to the election holding 53 out of 59 seats – 90%. In this term, it will have at least 46 seats – 78%. In some countries that is called a “supermajority”.

It’s unhealthy for democracy.

To illustrate an alternative, a proportional representation system, perhaps with a 5% threshold as in Germany and New Zealand, would leave Labor just short of a parliamentary majority. To govern, it would need to secure support of members of at least one other party, or to form some coalition.

In such a situation, most people would imagine a Labor-Green coalition forming, but why not a Labor-National coalition for example? Such balanced arrangements are commonplace in European democracies.

The possibility of a strong Green parliamentary representation could possibly have dissuaded the Cook Government from doing a deal with the Commonwealth to prevent the establishment of an environmental protection authority.

The table below shows how a proportional representation system, with a 5% threshold, would work out:

There are variants that can allow genuine independents to be elected. But the main point is that even though, with preferential voting, we have a more representative system than countries with first-past-the post voting — the UK, the US and Canada — we still have a system that is prone to deliver winner-take-all outcomes.

1. As at Thursday 13 March. ↩

2. In the non-metropolitan electorates – Albany, Central Wheatbelt, Geraldton, Kalgoorlie, Kimberley, Mid West, Pilbara, Roe, Warren-Blackwood – the average primary vote swing against Labor was 17%, a little lower than the state-wide swing.. ↩

Is Western Australia (once again) drifting away from the federation?

Undoubtedly, the McGowan Government’s handling of COVID contributed to Labor’s extraordinary win in 2021, which left the Liberals too weak to make a significant comeback this year. Western Australia was one of the few parts of the world that managed to hold COVID at bay while allowing life to go on as usual.

It is also one of the few places in the world where a government has been able to run a fiscal surplus in recent years, while providing a high standard of government services and investing in infrastructure for a growing population.

The state’s mineral endowments are a significant contributor to public revenue, and they will go on helping the state coffers. What wouldn’t the Victorian premier give to be in Western Australia’s situation?

Our federation has had a way of addressing some of those fiscal inequities.

From 1933 until 2019, Australia had a system for distributing part of public revenue through a process designed to ensure that each state had the same fiscal capacity to deliver public services. We have a body, the Grants Commission, whose task is to use objective criteria to estimate how much each government has to spend in order to maintain the same level of government services as other states and territories, and similarly to estimate how much each government can raise in taxes without having to subject their citizens to higher taxes than in other states and territories. This results in the development of formulas, or weightings, for each state, guiding how Commonwealth funds should be distributed.

Since 2000, the Grants Commission formulas have been used to distribute GST revenue collected by the Commonwealth. In earlier times, Western Australia was at a disadvantage – it has to provide public services over a vast area, and did well out of the Grants Commission’s redistributions. That all changed in the 1960s and 1970s, but because of temporary downturns in mineral prices, and lags in the distribution of GST revenue, by 2018 the state’s finances had become stretched.

In 2019, in an act of bipartisan bastardry, Labor and the Coalition got together to do a special deal to put a floor under the amount of GST revenue Western Australia would receive. It will never get less than 70% of what it would receive if funds were to be distributed on an equal per-capita basis. The Coalition hoped the deal would shore up their support in the 2019 federal election, and it worked. But it also worked for Labor in 2022, and Labor is not going to withdraw it before the 2025 election.

The politics and economics of the deal are covered in the roundup of 18 May 2024, under the heading “How the west won”, which has a link to Saul Eslake’s address to the National Press Club about the worst public policy decision of the 21st century (so far). Eslake also has a longer explanation of the deal in a February 2024 essay on his website.

In order to stave off opposition from the other seven states and territories, rather than simply redistributing GST revenue the Commonwealth actually promised to top up the funds to be distributed, should that be necessary. Eslake explains the fiscal details, but essentially it’s a scheme that requires taxpayers in seven of our eight states and territories to subsidise Western Australia, even though that state enjoys, and will surely go on enjoying, the country’s healthiest public finances.

As a Tasmanian, Eslake is clearly not enthusiastic about the deal, but he is also concerned about the total fiscal cost to the Commonwealth. Now that we are committed to a pre-election budget, the Commonwealth isn’t going to do anything to weaken its chances in Western Australia.

Of even more concern should be the basic agreement around our federation. Anyone observing recent developments in two other federations, the US and Germany, will be aware of the political consequences of big regional disparities. In comparison with those countries, and many other geographically large countries, Australia is remarkably free of large regional differences in living standards. Redistribution of government revenue has played an important role in keeping those disparities in check. Of course, those mechanisms cover only public services; they don’t address other sources of disparity, but they sure help.

Federal-state voting differences

Labor’s success in Western Australia raises questions about implications for the upcoming federal elections. Do voters differentiate between federal and state parties?

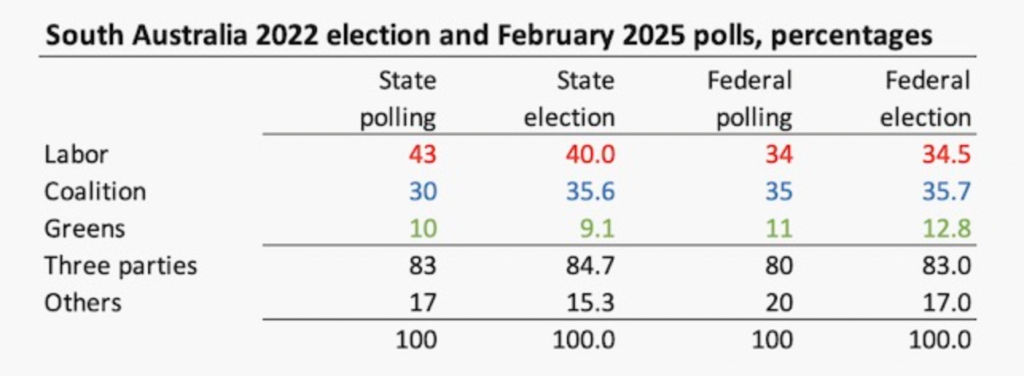

Market and political research company Demos has recently run two polls on voting intention in South Australia, one state, the other federal. The results suggest that some voters, at least, do differentiate between state and federal parties.

In South Australia, state Labor is polling far better than federal Labor. Also, support for the Malinauskus Government has improved from the 2022 state election, while support for the Albanese Government is about the same as it was in the 2022 federal election.

Caution should be exercised when one compares two polls. Each poll carries a sampling error, which means that estimates of differences are subject to twice the sampling error, but the differences are strong, as shown in the table below:

That suggests Labor enjoys something in the order of 9% greater support at a state level than it does at a federal level, while the Coalition has about 5% lower support.

If you click further through the Demos page you will find more detailed polling. That reveals that among South Australians, Malinauskas is clearly more popular than Albanese, and while they think the state is headed in the right direction, they are less confident about whether the nation is headed in the right direction.

One notable feature of both the state and federal polls is that support for others, than the three main parties, is higher than in the 2022 elections. Because opinion polls usually understate support for independents and minor parties, their gain is probably higher than is implied in these two to three percent shifts.

Climate 200 lists three community independents standing in South Australia:

- Rebekha Sharkie, recontesting the semi-rural Mayo electorate, which she won on a 62:38 TPP in 2022.

- Verity Cooper, contesting Sturt in Adelaide’s prosperous eastern suburbs, which the Liberal Party held with a 50.5:49.5 TPP outcome in 2022 after a 6.4% swing to Labor.

- Anita Kuss, contesting Grey, a vast outback seat, including Whyalla, Port Augusta and Port Pirie on the Bonaparte Gulf. It is presently held by the Liberal Party on a 60:40 TPP. Following the rescue of the Whyalla steelworks, Labor’s vote should be up on 2022, when it was only 21%. There are two factors that could shrink the Liberals’ 45% primary vote: Port Augusta is a significant hub for renewable energy, and the electorate has a large Aboriginal population. In spite of the Liberals’ strong success in 2022, Kuss seems to have a good chance.

Federally the poll is more promising for Labor than it is for the Coalition; the strong support Labor enjoyed in 2022 is holding. There may be some rub-off from the state government’s popularity and the miserable condition of the state Liberals, but it’s also notable that South Australia, with its population concentrated in Adelaide, may simply be displaying the normal urban-rural division of voting intention.

Republished from Bear weekly roundup, March 2025