We can’t unscramble the AUKUS and ANZUS eggs

March 25, 2025

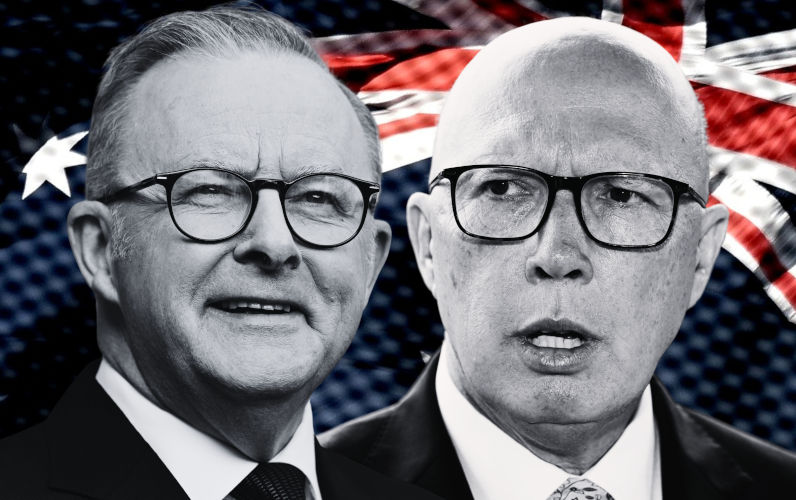

Before this election is much older, Anthony Albanese and Peter Dutton are going to have to determine where they stand on all the important issues. There’s a substantial chance that both are wrongly positioned and that each might have to face the other way, or perish politically. It’s not for an argument about which vista is best for Australia, alas. It’s for which is best for which leader, and which party.

Dutton, for example, likes to project himself as the strong man. The decisive man. The man of instincts and straight talking. Long before the election was called, he has been denouncing Albanese as weak and indecisive, a ditherer, slow to move, worried about negative reaction even to plainly good policy, such as fright about the backlash to gambling reform or electoral fairness. Albanese’s timidity is not an ideological matter, but a matter of personality. Dutton is seeking to undermine any remaining perception that Albanese can be tough. He also attacked his manliness and his projection of courage in action – by innuendo he’s a bit gay or limp-wristed. You only have to say that once or twice, then profusely apologise to the many rightly disgusted Australians, to implant the idea.

Sadly for Dutton, the election has been hijacked by Donald Trump. Dutton claims that he might be able to deal with Trump more effectively. Albanese comes from the political class Trump and his cronies detest. Dutton is not a full-blown Trump-ite, least of all on economic or defence policy, but he comes from a right-of-centre Queensland populist background. He has similar views on the woke state, on “inclusiveness”, and on the alleged superfluity of public servants. Even if Trump and Dutton never become bosom friends, surely one can see more chemistry and goodwill than between Albanese and Trump

It’s not us, it’s Trump. And it is not by any obvious script

Yet it is by no means obvious in the new world Trump is creating. Trump has rebuffed almost all of the traditional allies of the US. He has seriously undermined traditional defence and economic relationships, and in Ukraine, seemed to go over to the other side. He has imposed high tariffs on traditional allies. He has told nations such as Australia that they have been bludging under a US security umbrella. He gives no credit at all for the fact that Australia has always loyally joined the US in its military adventures, even when they have made no sense from Australia’s point of view. He now denies that the US has any civilising or pacifying mission in the world. Trump says the US is now governed only for how it economically benefits the US. Or, as Trump’s critics say, how it benefits Trump, his friends and the many bees in his bonnet.

The US with whom the next Australian prime minister will have to deal has virtually disowned NATO, an organisation which probably cannot be reconstructed without the US. America expects that NATO will become some sort of European Union-based organisation, but if it does it will lack access to American intelligence and command structures, and American logistics. It will lack the overall security guarantees that provided the foundations of an effective defence alliance that held the old Russian system of alliances at bay for 70 years.

Australia, because of ANZUS, and now AUKUS, and other traditions such as the Anglophone Five Eyes treaties, has been a part of the Western alliance. Its entry point brings in other nations of our region, such as Japan and South Korea, and to a degree India and south-east Asian nations. The old US nurtured these as it tried to build a coalition to push back at China. America felt itself losing power and influence as China expanded militarily, economically and politically into the Indo-Pacific, and the South China Sea. But America now sees these allies as similar free rides who should at the least double their defence budgets. It is imposing tariffs on its friends as well as on China. The trade war against China continues, but a good deal of the military rhetoric has been toned down. Trump seems hopeful that he can make trade deals with China that might resolve many of the conflicts. He is sick of American involvement in countless faraway wars and wants an American retreat from the world.

Australians are watching these developments with considerable anxiety. They are well aware that they have very little influence over Trump and his team. The idea propagated by Dutton that he might have been more successful than Albanese in holding off tariffs, or in getting some exemption, has been disproven by events. No other country was able to get concessions. We now know that Trump and his colleagues had decided in advance that there would be no special deals or exemptions.

Most voters know what Trump has been doing. But their anxiety about the future is not being guided by our politicians

Trump’s particular animus against Canada, with which the US shares thousands of miles of a peaceful border, underlines the sudden loss of Australian influence. Canada has imposed retaliatory tariffs, but nearly all of the players in Australia (and, for that matter industrialised allies who were once US friends) think that letting the tariffs fail on their own merits, rather than by tit-for-tat, is the better response. Canadians are part of the national conversation in ways that Australians are not.

Old allies are now judging the US for its reliability and trustworthiness. And not only as a military partner or as an arms depot. But as a nation which might plant kill-switches into its equipment, or refuse, despite promises to resupply or maintain what has been sold. Likewise, one which might abrogate contracts if it suited its economic interests. Some NATO partners, including Canada, have cancelled orders for American aircraft to explore options for a Euro-fighter, whose powers they can control, particularly when they are most necessary. The experience of supplying arms to Ukraine has demonstrated that much expensive American equipment is now obsolete because of drones.

An Albanese or a Dutton must necessarily ask himself about what American action means to the future of AUKUS. Is it a conversation only for his mates, or with taxpayers? Should Australia simply repudiate the deal? Americans at the highest levels have expressed doubts about whether the US can deliver on its commitments. The US (and Britain) have the power to walk away. Strictly, the right of Australia is much more restricted, and might well involve damages – as when Scott Morrison abrogated the French subs deal. Given the forward commitments of hundreds of billions of dollars, walking away now might be cheap at any price, and allow Australia to re-imagine a completely different defence posture not locked into the US system.

That might involve an inquest into how the Australian Government secured national interests in signing the contracts. It simply cannot be said that the possibility of a Trump or an American repudiation was not a contingency for which Australia should have prepared.

These are political questions, not technical or financial policy questions essentially for expert advice and action. The ones who have to answer them are politicians. While both Labor and the Coalition have long been locked in alliance with the US, Labor has been historically more cautious about over-commitment to the relationship. In recent times, however, Albanese and his defence minister have reached new heights of sycophancy and subservience. Whatever the hopes invested, they have not paid off. Australia would have been better served by a more detached, and somewhat suspicious, relationship. We were on different sides of the table. The ANZUS and NATO relationships have not broken up because of bad faith or change of policy by alliance partners. It has happened because of unilateral (and unconsulted) political decisions made by the US. America has the right to change its mind, but it must accept responsibility for some of the ill-effects, including bad blood and a sense of betrayal.

Both sides of Australian politics have considered the possibilities of dramatic changes of international circumstances. Over time, they have taken a big gamble on an automatic defence partnership provided, in effect, by going along with anything the US wanted. Now we must consider where this “insurance policy’’ leaves us. And what impact it has on vital US military assets in Australia, such as Pine Gap.

What’s next is for politicians and the public, not the defence establishment. Voters should be suspicious about vested interests

One can expect that the defence, intelligence and diplomatic establishment will be unanimous about Australia doing everything it can to preserve as much as possible of its defence and trading relationships. There is no gymnastics some senior officials would not perform, if only because they have come to see US success as the basis of Australian security. It hasn’t stopped Trump waving us off. He doesn’t care.

Third-party groups, particularly the Greens, must be part of the debate. Apart from saying “I told you so” they will see the problem as an opportunity for a completely different type of international relationship thinking. Independent thinkers and academics have also warned of what has come to pass, though whether those who have been proven wrong will now let them in the door is far from certain.

Australian voters have yet to see frank assessments of how Australia sees its position in the region and in the world in three years time. On their records, we can expect leaders on both sides to be reluctant to confide in the Australian people. Voters should not accept this or take them on trust. We are in our rotten position because of rotten political judgment. On both sides of politics. That will not be resolved by expecting better next time.

It is time for some accountability – from both politicians and the carefully cultivated constituencies who have benefitted so handsomely from a shaky status quo. We deserve fresh thinking. We should not assume that the Coalition can be predicted to be “owned” by American lobbies. There is a long history of some Coalition people being concerned about over-dependence.

Dutton would, no doubt, like Australians to see him as the safer choice as champion of a more secure Australia. In his style of argument, Labor are always traitors, fundamentally unsound on national security. He deserves close scrutiny in his assumptions as much as his “facts”. Neither the Democrat nor the old Republican ranks see the world in the same way as Trump and his Trump-ites. Nor can it be said that the modern Trump-ite approach is more (or less) “conservative” than the policies of the past. But the next regime (if there is one) cannot reconstruct the old relationships.

Albanese thinks he’s the man for the task, though he has yet to explain why, or to what purpose. Neither he, nor his deputy, Richard Marles, has shown any aptitude of vision for defence, a reason why they are so shy of debate or levelling with the Australian people. It will be interesting how much the words “trust” and reliability hang about them. No doubt, Albanese hopes that he is the choice not on his own account but for distrust of Dutton.

Dutton has spent his political career selling himself as a natural social conservative, focused on protecting Australians from the risks of aliens and criminals in the community. He has a strong distrust of anything he characterises as “woke”.

He has no noticeable empathy with Indigenous Australians, the source of much of the crime he had to deal with as a cop, or with many of the modern class of immigrants and refugees. His personal fortune, self-made in partnership with his wife and his father, comes from land development, buying and selling houses, and farming millions in public subsidies for child-care. He identifies with salt-of-the-earth building tradesmen, and regional straight-talking Australians. He is not greatly impressed by professionals, academics, bureaucrats and white-collar workers. He has made no effort to reach out to moderate liberals, including those whose once-safe right-of-centre Liberal seats have now gone, possibly forever, to community-based moderates and Teals. The future of right-of-centre parties belongs by becoming more conservative, not reaching out to the centre, he believes.

In ordinary circumstances that might be all very well, and issues that crop up, such as the cost-of-living, high interest rates and energy prices might be thought of as made in heaven for him. As with a long record, from being a senior and prominent member of the past Coalition Governments in police, deportation and immigration matters. And an important role, as minister for defence, in establishing the AUKUS regime and its nuclear submarine deal. This is the platform from which any Coalition leader hammers themes of Labor incompetence in economic management, propensity for bigger government and general hopelessness. Against these scourges, leaders like Dutton show resolution, firmness and a distaste for the heresy that more government and more public spending solves all social problems.

Dutton differs from the usual commissioned ranks by having no close interest in, or attention to, matters economic, though he can compensate with a certain natural indifference to the situation and suffering of those who are poor, sick, disadvantaged or failing to have a go. He is firmly of the view that those dependent on welfare should be treated meanly, with suspicion of fraud, and made subject to arbitrary management that effectively punishes people for their situation. The mindset that gave Australia Robodebt — the worst public administration scandal in Australian history — comes from the engine room of the Abbott, Turnbull and Morrison Governments. Dutton was there, in fact and in spirit. On matters such as this, character and past performance matter. For both Albanese and Dutton this is the baggage they take to repairing our defence.