Australia’s fading democracy calls for radical rethinking

April 12, 2025

Donald Trump has declared a global trade war and unsurprisingly America’s most faithful ally has not been spared.

Though the announcement was widely expected even before Trump assumed office, Australian politics was still firmly ensconced in the realm of make-believe. Predictably, Trump’s tariff rampage has left Australia’s aspiring prime ministers floundering.

At the midpoint of the national election, neither side of politics has yet said anything of substance on the future of international trade, let alone Australia’s future relationship with the US.

One can only assume they are waiting for further instructions on what to say and do from powerful interests and strategically placed advisers within and outside the country. They may also think it unwise to take the electorate into their confidence and safer to postpone any announcements until after the voting ritual has reached its finale.

Nor is there much evidence that the political class is tuned in to the other pressing challenges facing the nation. The approaching climate catastrophe has evoked little more than palliatives and pious hopes, while Australia’s stark wealth divide has been met with studied silence, as has the Uluru Statement from the Heart and the urgent task of reconciliation with First Nations.

Insipid electioneering is but a symptom of a deeper ailment. Parliamentary representation can no longer be said to reflect the will of the electorate.

The disparities in the value of each vote are well known, but they have become starker. At the 2002 federal election, the Greens secured 1.8 million votes of the national total and four lower house seats, whereas the Nationals secured 10 seats with only 528,000 votes, and Labor 77 seats with only 4.8 million votes.

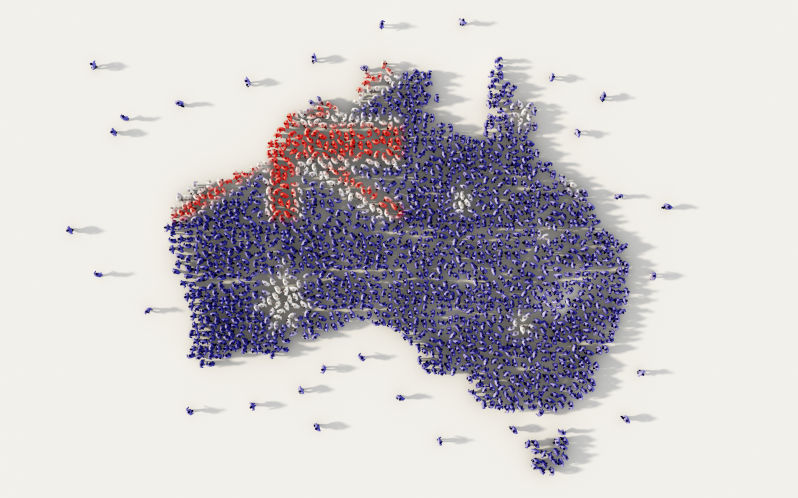

The representational deficit is just as striking when we consider the ethnic composition of the Commonwealth parliament. Though 23% of Australians are of non-European ancestry, they account for only 6.6% − or 15 of the 227 MPs. Australians of Asian heritage make up 18% of the population, but only 4.4% of MPs.

The failings of Australia’s representative democracy run deep. Institutions that are said to uphold the principles of integrity, transparency and accountability in government are ineffective, at times bordering on the useless.

The current regulatory regime does not deliver the proper functioning, let alone public oversight of parliaments, political parties, or media and public broadcasting.

Law reform commissions, ombudsman offices and the Human Rights Commission are invariably deprived of the powers needed to make their presence felt. And the more consequential recommendations of royal commissions are routinely left languishing at the bottom of the political agenda.

The net effect of these multiple shortcomings has been distressing, but foreseeable. Most Australians are still hanging on to the idea of democracy, with 72% still of the view that democracy is preferable to any other form of government. But when it comes to democracy as it is currently practised, public perceptions are decidedly negative.

A nationally representative survey of over 3,500 Australians conducted last October by the ANU’s Centre for Social Research and Methods found that 62.2% of all Australians had little or no confidence in the institutions of ‘Federal Government’. A 2023 survey found that only 26% of all Australians trusted political parties, while a Guardian Essential Poll in July 2024 revealed that “75% of respondents believed politicians enter politics to serve their own interests.”

The time has come for some radical rethinking on the future of democracy in Australia as in other Western “liberal democracies”. The institutions and practices of representative government may have held promise in an earlier age. But in today’s vastly altered circumstances, voting every few years for this or that candidate for public office cannot, of itself, deliver democracy.

We have reached a point where we may need to retrieve some of the key principles which governed Athenian democracy – a form of government which prevailed from the 5th to 4th century BCE. Under this system, all male citizens (the demos) had equal political entitlements, freedom of speech, and the right and duty to participate directly in the making of decisions and serve in the institutions that governed them.

Various labels, notably direct democracy and participatory democracy, have been used to describe the Athenian model. But if the intention is to explore how best to apply the model to contemporary life, there is good reason to think that deliberative democracy holds greater promise.

In deliberative democracy, citizens engage in decision-making with due regard to rational argument and knowledge of the relevant facts – a crucial consideration in the age of fake news, misinformation, propaganda, and the filter bubbles and echo chambers of social media.

The question is: how can deliberative legitimacy be achieved in societies like Australia where face-to-face gatherings in large numbers and across huge distances are not feasible? Community gatherings in localities across the country may have an important role to play, but wisely applied, advanced technologies may also have much to contribute.

A degree of experimentation is therefore needed to see what human ingenuity can do to breathe new life into democratic processes at all levels of human governance – from local to national to global.

With this in mind, Conversation at the Crossroads is convening an Online Citizen Assembly in late April in the lead-up to the Federal election. The first of its kind in Australia, the assembly will use the most advanced technology available for this purpose – developed by Stanford’s globally recognised Deliberative Democracy Lab.

The Assembly is open to anyone who wishes to participate, not least readers of Pearls and Irritations. It convenes in two stages, first in small groups, and a few days later in plenary session. All participants are given equal time and opportunity to express their views and concerns. Registration can be accessed here.

The focus of discussion will be the Coalition’s plan to build seven nuclear power stations by 2050. Nuclear energy has been chosen because it is a highly contested issue, and, importantly, because it helps open up a discussion of three pivotal questions: Australia’s energy future, the implications for climate change policy, and the prospects for democratic deliberation and decision-making in this country.

It will be a humble beginning to be developed, refined and scaled up in the light of experience.

The democratic ethic is under significant threat. Bold new initiatives are needed to breathe new life into a noble, but ailing ambition.